[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Overdub: Hello, welcome to The Story of Woman, the podcast exploring what a man-made world looks like when we see it through her eyes. Woman's perspective is missing from our understanding of the world. This podcast is on a mission to change that. I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein Lau and each episode I'll be speaking with an author about the implications of her absence - how we got here, what still needs to be changed, and how telling her story will improve everyone's next chapter.

[00:00:34] Section: Episode level introduction

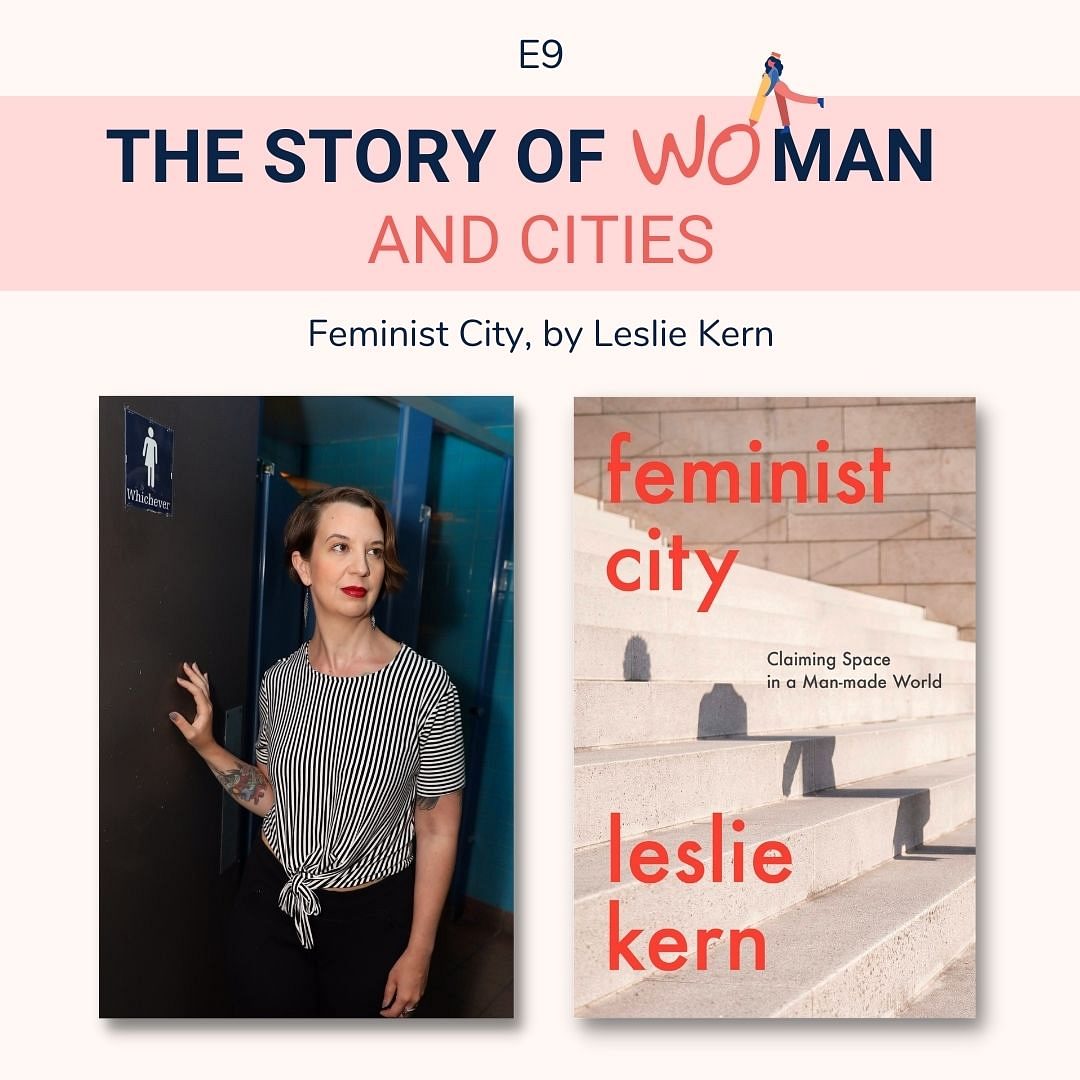

[00:00:35] Anna: Hey there, friends. Welcome. Welcome. I'm so happy you are here. We've got a great conversation today about women and cities.

We tend to think about our cities and our neighborhoods and our homes as these fixed environments, we interact within- something separate from our social systems and not really capable of discrimination or bias, but like everything else in our world cities are shaped by gender. Someone had to design them and the city planners, engineers, architects, historically, these have mostly all been men. And as we'll hear from our guests today, this doesn't mean men inherently designed cities to exclude women, but it's inevitable that there will be tunnel vision when there's only one perspective involved.

So of course the best way to start to see how our cities are not serving everyone is to look through the perspective that has been left out. And that is exactly what our guest does today. Leslie Kern is the author of Feminist City and she exposes what is hidden in plain sight by taking us through the city from a woman's perspective. She covers everything from the fact that wind tunnels and snowplows and buses and other integral parts of our cities were designed for the average male body, to the challenges of being a mom and the city, or simply being left alone in the city as a woman. Her book also gets into the revolutionary power of female friendships, which sadly we didn't have time to get into today because it's a phenomenal chapter, so you'll just have to read the book to learn more about that. But a big topic of discussion today is the always present female fear. I know all of my female identifying listeners will be very familiar with. We as women have many tactics to ease this fear when walking alone at night or down certain streets, like pretending to be on the phone, texting friends, avoiding shortcuts, and much, much.

And while this is a common experience amongst I'm going to go ahead and say all women it's also something we don't even think twice about because we just assume that that's how it is. Or, you know, maybe it's something we just personally do, or maybe we even think that we are being a little irrational, but as you will soon find out it is none of the above. There is a reason and it's not just in our heads and we will get into all of that today.

Leslie Kern, the author of Feminist City is a feminist geographer. She holds a PhD in gender feminist and women's studies, and she is an associate professor of geography and environment and the director of women's and gender studies at Mount Allison University in new Brunswick, Canada. She is also the author of Sex and the Revitalized City.

And the four quotes you will hear read during the interview are taken directly from her book, Feminist City.

We've got a great conversation today. Looking at all the ways inequities have been embedded into our streets, homes and neighborhoods, and how by re-imagining our cities, we can build more just and sustainable environments for all.

So pop in those headphones, go for a stroll and enjoy, but only if it's not too dark or dodgy, of course.

[00:03:54] Section: Episode interview

[00:03:54] Anna: Hello, Leslie. Welcome. Thanks so much for being here.

[00:03:58] Leslie: Thank you for having me.

[00:04:00] Anna: Yeah. As a current city dweller, I'm really looking forward to this conversation.

Your book resonated on so many levels and it has really allowed me to start seeing my own existence here in a clearer light, because you know, when I first moved to a city 10 years ago now, any new way of existing, I kind of just thought, well, that's just how it is in the city. You know, 10 flights of stairs to get down to the tube.

That's just how it is because the trains underground or creepy underpass that I don't want to walk through at night. That's just how it is. So I'll walk around. But your book has taken all of these seemingly innate characteristics of the city and really exposed them for what they are, which I guess are essentially problematic designed flaws.

But this is also deeply embedded that I'm sure you get asked a lot, what gender has to do with cities in the first place. I mean, after all cities are made of concrete and bricks and glass, so how could it possibly be feminist?

So to start, could you please explain what exactly gender has to do with cities?

[00:05:12] Leslie: Thanks for the question. You're totally right. It's not intuitive to look around the built environment and to either see gender or to get a sense that there's anything to do with sexism or gender discrimination in the spaces around us, but we can think about this in so many different ways. One, the question of who built the city and who continues to build the city, primarily professions, such as architecture, planning, policy design, civil engineering, all of these things are dominated by men doesn't mean that they inherently make sexist spaces, but their world and life experiences might be quite different than, than those of women.

And in many ways, the city has been set up to support the lives and needs of what was assumed to be a typical man in the 20th century, a breadwinning husband and father who would commute from the suburbs into the central city for work on a nine to five schedule in a linear journey, either in a car or on a train.

But you know, women's day to day lives. Don't tend to look like that. And so the city is not set up as well for them as it has been for men and there's lots of other ways just in which the values of the city tend to reflect what we might call typically masculine values of the economy of the world of paid work as opposed to things like care work which is still predominantly the responsibility of women in many parts of the world.

[00:06:48] Anna: You said the patriarchy is written in stone was a line that I liked from the book and that became very apparent the more that I read, so I want to get into the implications of all of that, but first, a bit more about your career. You're a feminist geographer, which may be a new concept for some people. Could you tell us what is feminist geography and how important is it to have a geographic perspective on gender?

[00:07:17] Leslie: Yeah, feminist geography is a way of looking at the world that tries to understand how ideas about gender in terms of gender roles, gender relations, even gendered bodies come into being in part through the way that they are expressed in a human made environment, such as cities. So to me, it's always been like adding a, kind of a third dimension to a feminist analysis of sexism, discrimination and gender inequality more generally.

So we could look at law, we could look at education, we can look at pop culture and see lots of examples of ideas about gender and sexism and so on. But feminist geography says we can also look at space, the spaces around us, everything from our homes to our streets, to our parks and public institutions, and also see ideas about what are the right ways for people of different genders to act and behave, and also expressions of gender dominance and oppression in those environments as well.

[00:08:22] Anna: Yeah, you said, it's not quite the elementary geography we might be thinking about with our maps and everything. It's really the human relationship to our environment, which really paints the picture of that. So let's get into the chapters. I love how you divided the book up by different ways of being in the city- as a mom, as an individual, as a friend and protest, I thought that was really unique. And you took us through your personal story within each of these, which made it a very enjoyable read and a lot less like an academic textbook and more like a personal narrative with a lot of eye-opening information.

So the first chapter, which is called the City of Men, tells us a bit about that history that you've touched on the history of cities..

[00:09:06] Book excerpt: "Women still experience the city through a set of barriers – physical, social, economic and symbolic – that shape their daily lives in ways that are deeply, although not only, gendered. Many of these barriers are invisible to men, because their own set of experiences means they rarely encounter them. This means that the primary decision makers in cities, who are still mostly men, are making choices about everything from urban economic policy to housing design, school placement to bus seating, policing to snow removal with no knowledge, let alone concern for, how these decisions affect women."

[00:09:44] Anna: Could you tell us, you know, What is your definition of a City of Men?

[00:09:49] Leslie: Sure. On a basic level, I'm talking about the city as a place that has been both built by and designed for the lives and comfort and bodies and needs primarily of men. And at the same time has often seen women and women's bodies and women's needs potentially as a problem for this city, something to be solved, or contained, or maybe even limited in terms of their presence altogether in the city.

Historically, when we think about the growth of cities in the global north, during the industrial revolution, when there is rapid increase in urban populations and people all over the place were wondering, what does this mean for society? One of the things they were really concerned about is what does it mean for women and for the virtue of women or at least of certain women.

And the fear was that women out in public would either be mistaken for prostitutes or their virtues and morals would be tested by rubbing shoulders with the working class and immigrants and poor people. And there was this sense that women were so potentially vulnerable and needed some kind of extra control placed around them.

So from that, in part, we see the development of the suburbs and if we fast forward to the 20th century, thinking about the city of men compared to say the suburban environment, which was very much, you know, a feminized environment, the place of the home, where the post-war homemaker was supposed to be devoting all of her time and energy to the creation of a domestic bliss in the post-war world.

So yeah, the City of Men is a concept that's trying to encapsulate both a kind of historical trajectory of who the city has been built for and a sense of the general exclusion of women and women's priorities from urban space.

[00:11:42] Anna: And, on the actual design of the cities, you had some very fascinating examples from wind tunnels to public transport systems, to snowplows, to not being able to reach the handles in a public transportation bus or tube or underground. Can you tell us about one of those I'm trying to think of which was the most eye-opening, maybe the wind tunnels in Toronto?

[00:12:08] Leslie: Yeah. Sure. So typically, in so many areas of design, not just urban design, but so many areas, an average male body is taken as the standard around which all sorts of designs are made, including things that have to do with human safety and human comfort. So the wind tunnel example came from a set of city of Toronto guidelines around, uh how much wind force was acceptable for pedestrians to experience when you know, new buildings go up in they create a wind tunnel effect. And of course that acceptable wind force was calculated based on what would be comfortable for an average adult male body, which is not something, first of all, that every man is going to conform to, but certainly many women won't of course, children won't maybe senior citizens won't, people with disabilities won't. So a whole, a huge range of people are really excluded. And yet we still continue to think of that body as the norm and everybody else as the exception that we don't really need to pay attention to.

[00:13:14] Anna: And the irony as well is the universal standard could actually be the niche because men would make up the minority if you look at a cumulative of women, people of color, poor people, seniors, people disabilities, and everyone else, all those quote unquote niche groups.

[00:13:30] Leslie: Absolutely. So, yeah, I like to think that if we started from the perspective of, you know, the true majority of people, which would include many who identify as men as well, then we might have a very different picture of what the norm should be or who should be placed at the center when we come up with various designs.

[00:13:50] Anna: So the second chapter is called the City of Moms. It seems pretty obvious that if cities were designed for a quote unquote standard male body, they most certainly were not designed for the bodies of pregnant people. You say that your pregnancy and motherhood made the gendered city visible to you in high definition. Can you tell us about that experience and what it means to be a mom in the city?

[00:14:15] Leslie: Sure. You know, I certainly wasn't ignorant of sexism and gendered realities of city life prior to that, you know, the experience of being catcalled on the, city streets will remind you very quickly of gender imbalances, but when I was pregnant and then when I had my daughter and she was an infant, suddenly it was more than just like rude people in the urban environment, it was the physical infrastructure itself was suddenly a barrier that I had never experienced before, as an able bodied young person. It was very difficult to just moving through the city with a stroller, finding places to sit, places to change a baby, places to nurse a baby. People would give you hostile looks like, "what are you doing here?"

And it was really one of the first times that I had this sense of, oh, I kind of don't belong here at this time, or there's a sense that I shouldn't be doing these activities in public spaces that I and the baby are really a nuisance to the true, you know, user of whether it's the subway train, the cafe, the lineup at the grocery store, all of these places, it was like, oh yeah, you don't really belong here anymore.

[00:15:30] Anna: It's interesting. I hear you say it makes you feel like you don't belong because I think that's our first instinct is about us instead of this system, and this design, you know, did not include pregnant people in the first place.

[00:15:45] Leslie: Exactly. Yeah it's almost as if it's just assumed that somehow parents with children don't need access to public transportation and don't need space on sidewalks, and again, it just kind of shows maybe the blinkered visions that have often been at the heart of design of so many urban spaces and systems.

[00:16:07] Anna: So you made a really important point that the lack of public infrastructure for care work, deepens inequality among women, as we participate in multiple layers of exploitation, just to keep ourselves afloat. I think this is a really important point and something that needs to be talked about more. So can you elaborate on that and describe these multiple layers of exploitation?

[00:16:32] Leslie: Sure. Well, given that there's still is this gendered imbalance in terms of responsibilities for care work, like taking care of the home childcare, elder care, and even community labor, if you will, the solution has not apparently been to either equally distribute that amongst men and women, or, even better, in my opinion, to truly collectivize it as a society.

What has more often happened is that we kind of download that responsibility onto a poorly paid workforce, largely comprised of women, but also racial minorities, recent immigrants, and so on to do the work of childcare, of cleaning, of preparing meals, of laundering, clothes, all these sorts of things that take up a great deal of time for many women.

And so that's what I mean by these kinds of layers of exploitation, because we haven't really publicly solved or truly tried to solve the care work dilemma, it just means that we are shifting the responsibility for it in ways that are not really, truly liberatory for her most women, they kind of allow some women at the top to like climb up a little further on a particular ladder, but they're not really lifting up the women who are kind of at the bottom of that pyramid.

[00:17:52] Anna: Yeah, I think that that's crucial point to include in these conversations so that the responsibilities don't just get shifted to other women.

[00:18:01] Leslie: For sure.

[00:18:02] Anna: And you acknowledge your own limitations as a white middle-class person and that your expertise is rooted in global north cities and Western bodies of research.

Can you talk to that? How much of this book is relevant to cities in the global south? And is there anything that we should keep in mind while reading your book or listening today in terms of considering women in cities outside of this scope?

[00:18:26] Leslie: Yeah, absolutely. Some of the things that I think are, if not universal, kind of close to being universal concerns, things like public transportation, women, all over the world report high levels of harassment and even sexual assault on public transportation. Um, a lack of accessibility, a lack of kind of child-friendly access to public transportation.

This is very common around the world and certainly issues safety in public are also quite common, so I think there's a lot of space for solidarity there. One of the things that people, I hope, should take away and something that I've been able to increasingly recognize over the last couple of years of sort of talking about this book with so many people, is that it doesn't require, you know, Western global north feminist expertise to fix these problems.

In fact, in hundreds of cities in the global south women are already working on these problems and some, you know, really innovative solutions come from the global south. So I always want to be sure, even though I have not been an expert on those things, I'm learning as I go here to, um, make sure that it doesn't seem like, oh, only in the global north, can we innovate or truly address these issues when actually so much of the activism and policymaking is coming from the global south and we would do well to pay more attention to it than we typically do.

[00:19:53] Anna: Do you have any examples of some things that have come out from the global south?

[00:19:57] Leslie: Sure. The app that's called safety pin which is gaining global attention is an app that was created by an Indian woman and it's meant to allow women to kind of report incidents of harassment or fear around the city and the idea is to kind of create an accessible database and to sort of empower women to feel like they can take back some control of the streets and public space. So, you know, it started out as kind of a local intervention, but it's available in many places now, and the creator of the app speaks better internationally and so on. And this is one example that, that comes to mind.

[00:20:38] Anna: Oh, very cool. I'll have to check that out after this. You touched on this a bit in the beginning, but I'm curious if you have anything else specifically to add about the suburban lifestyle and how we see those gendered effects of the past still linger again today. As a person born and raised in the suburbs, this rang quite true in terms of my experience and what I've seen there.

So how do we see that play out today in the design?

[00:21:05] Leslie: Yeah. I'm with you. I was also raised in the suburbs and even though we might think that a lot has changed in terms of families and gender norms since the fifties and sixties, and many things have, our built environments kind of outlast some of our social norms, right, and so we're stuck with them for a long time and the suburbs example of this, you know, built with that idea of a gender division of labor, of the male worker leaving the home and the women staying at home to take care of the house and children. And we see today that this remains a constraint in that the suburbs are less connected to public transportation, they are less integrated in terms of different uses. It's further to travel to school, and then to work, and then to the grocery store, than urban environments where things tend to be in closer proximity to one another. So it makes juggling the demands of paid work, which the majority of women do outside or inside the home as, as well as unpaid work, extra difficult, you know, urban environments are not perfect for that, but they are sort of one way that women have tried to kind of solve for that problem by literally bringing all of those closer together, which, works for some women, not, not for everybody, but the suburbs still remain this environment that just creates this kind of friction, where even if you want to be, you know, a modern egalitarian family, you may find that actually it doesn't work that well for both parents to have full-time jobs outside of the home and still try to take care of all of the domestic responsibilities of family life.

[00:22:44] Book excerpt: "A feminist city must be one where barriers - physical and social - are dismantled, where all bodies are welcomed and accommodated. A feminist city must be care-centered, not because women should remain largely responsible for care-work, but because the city has the potential to spread care-work more evenly. A feminist city must look to the creative tools that women have always used to support one another and find ways to build that support into the very fabric of the urban world."

[00:23:16] Anna: Yeah, definitely. Shifting gears slightly before we get into the next chapter, because we can't get through a whole hour without talking about COVID unfortunately, as much as we might want to. As you pointed out, you know, it's obviously no secret that the COVID-19 pandemic has really brought into light how badly we've neglected care infrastructures and how much we rely on the un and underpaid labor of feminized and racialized workforces to patch the gaps.

You know, we've been hearing about the decades of progress being rolled back, and some people are even calling it a she -session so from your perspective, how has the pandemic shed light on this problem and how can the design of our cities- the buildings, public spaces, transportation- how can all of this play a part as we move into the recovery phase?

[00:24:07] Leslie: Well, I think the pandemic has shed light on it and not many people were, I think quite frankly, shocked at the extent to which even temporary school shutdowns and so on led to this massive ripple effect of either burnout for women or forced resignation from their paid work, showing that this balance that the ability for women to work outside of the home and to handle those domestic responsibilities was a really fragile balance.

And when something in the system changed and changed as quickly as it did, the whole thing started to fall apart for many people. So there was this kind of collective realization maybe of like, oh yeah, we've been really just holding this together with like hope and bubblegum for a really long time.

What it's kind of forced me to think more about as a feminist geographer, as someone who's interested in cities is not just the question of like, okay, so how do you get men to do more stuff around the house? Like, yes, that needs to happen. And for any men listening, please do more. You can always do more, but it's not just about, you know, the heterosexual marriage and the heterosexual household is not just like this war of the sexes.

It's actually a collective societal problem. And from an urban perspective, we might ask questions like, how can we use space differently? Right. Like how can we not hide all of this care work away in the private space of the home, make it the responsibility of individuals. How can we bring it literally into the public, both in outdoor and indoor public spaces, how can we find creative and frankly, more environmentally sustainable ways to share the labor and resources that go into cooking and cleaning and caring for children, growing food, looking after elderly folks, all of those kinds of things that we need to do.

And the hope, the dream, the utopian vision that I have is that if you can shed light, like literally bring it into daylight, then we might actually value this labor, right. Instead of seeing it as unskilled as just something that women do naturally, as like,

[00:26:24] Anna: That keeps the whole economy going...

[00:26:25] Leslie: Yeah. It's something that you can pay minimum wage or below for people to do and say, oh yeah, like without this, as you say, none of the rest of it happens, right. So can we actually take shared responsibility for it and see it for the truly, the most valuable labor that there is in the world.

[00:26:47] Anna: So the next chapter was the City of One and you started this chapter talking about how for some people, phones and headphones are more than a form of entertainment. They create social barriers and are part of our urban survival toolkit. I loved this idea and it's not anything I had ever really considered, but it's so true. So kind of a multi-part question here.

What do you mean by the City of One, why is that important and why do women need headphones to experience the city in this way?

[00:27:20] Leslie: Yeah the City of One is kind of about the idea that for many people, one of the great pleasures of city life is the ability to blend into the crowd to be anonymous, right? To, to not walk down the street like I do in this small town and everybody knows your business, and everybody wants to chat and say hello. To be independent, to be able to construct a kind of a new identity for oneself and even going back to kind of, like late 19th, early 20th century, writings about the city, the idea of the flâneur , an individual who could be a true urban spectator, just enjoy the thrum of city life, that pleasure of people watching. And yet just be one of the crowd has been kind of held up as one of the ideals of city life or the true joys of city life. But I think for many people in cities, women included, that has not really been available to us.

And there's a number of reasons. One might be a sense of fear. So needing to kind of have almost eyes on the back of your head, a sense of vigilance that might prohibit you from fully slipping into that sort of pleasure of just wandering, blending and watching, because you are aware that you are likely being watched as well, right, so can you sort of truly blend in if you are the watched, if you are being objectified right by others. And of course the all too common experience of unwanted conversation, attention, and even physical contact that happens in the city. So when I was writing about headphones, phones, your book as this sort of indication of a social barrier, that's what I was getting at that it's not necessarily that people don't want other human contact or that we're all totally, you know, isolated and cut off from one another.

That for some groups, this is the only way that we can get a moment of peace, right. To sort of signal like, don't talk to me right now. I'm reading my book and on the Canadian edition of Feminist City, it's a, it's a paperback. And on the back flap, if you, if you open up the back flap, it says, fuck off I'm reading.

And the idea was that if you were standing on the subway reading and someone comes up to you and sort of open the flap....

[00:29:47] Anna: I think all books need that.

[00:29:49] Leslie: Absolutely. It's the survival toolkit for sure.

[00:29:52] Anna: But, I think that you made a really good point and it's not that it's technology that makes us anti-social, it's people make us anti-social and technologies are remedy to help with the discomfort that that brings. And, you know, you talked about that contradictory, gendered socialization for women that, you know, we need to be aware of strangers, but also, always be nice to strange men that might try to talk to us. So it's that constant balancing act of how to respond when there is someone trying to talk to you.

[00:30:26] Leslie: Yeah. And you really can't win.

[00:30:29] Anna: No? Okay. So there's no solution that you would provide for us to win this game?

[00:30:34] Leslie: Well, I don't know that that solution can come from women. I think there's a solution, but it's one that maybe men need to devise and to practice.

[00:30:43] Anna: Great point. Once again, it's not a fix the women problem.

[00:30:47] Leslie: Yeah.

[00:30:49] Anna: And in that same chapter, you talked about the dreaded "smile" request, which kind of comes along with these as well. So not only are we often not allowed to be alone in this space, but we're not allowed to be alone with just our natural resting face because we'll be told to smile.

[00:31:05] Leslie: And it's interesting, I've seen, you know, kind of on social media women talking about how much they've appreciated wearing a mask in public, because it has totally eliminated that kind of interaction. Nobody can see whether you're smiling or not, whether you have your bitchy resting face or not. And it doesn't make sense to tell anybody to smile. So maybe we'll be keeping masks for even a little longer than we need to.

[00:31:29] Anna: It's so true. I have that thought and I will definitely be continuing to wear mine and I sometimes am singing underneath as well so I'll continue that habit.

[00:31:38] Leslie: Me too. Me too.

[00:31:40] Anna: Love it. Um, okay. I'm going to take a leap here. What about manspreading? They want to take up more geography, any correlation with, you know, this problem of men taking up more space physically and women being told to kind of shrink themselves and be as small as possible?

[00:32:00] Leslie: Yeah, I think it's unfortunately a trait of, I mean, I think we can call it kind of toxic masculinity, a sense of entitlement to take up space in public, a kind of lack of consideration for other people, a lack of awareness of how, the way that you carry yourself, the noise that you make, the space that you take up affects other people. And it's, you know, not to say that all men are intending to do something hostile, but again, being socialized into a certain set of norms that sort of say, this is okay, this is normal. I see other people doing it. And when you pair it with the fact that if you, you know, scan your eyes around the tube you'll often see women literally shrinking themselves are holding their bodies really tight. Their elbows are tucked in, their knees are squashed together. Their purses are tucked away underneath their legs. Their shoulders are hunched under. Um, and they're trying not to take up any more space than is humanly possible. And when you look at those two things, you think, yeah, this is not natural, right? There's something going on here, but how we've been taught to, you know, be like literally to be physically embodied in space.

[00:33:17] Anna: Yeah. So one last question with the City of One and being able to be a flâneur and be alone in the city. How does this play out for Black and Indigenous people and people of color?

[00:33:31] Leslie: Yeah, I think it plays out often in very dangerous and, sometimes potentially fatal ways in that always being marked as different, always having people question your legitimate presence in space, the association of people of color with criminality. So the assumption that simply by existing in a space, you may already be doing something wrong.

The regularity with which people call the police for simply the presence of Black, Indigenous or people of color in public spaces. And we know that that often leads to violent or fatal encounters. So there's a real risk, a real genuine safety risk simply again for existing in public. Right, and we, you know, hear people talk about walking while Black, driving while Black, right.

And these represent that you're doing a totally banal everyday experience that many people, if you are white skinned, don't think twice about right. And it would be a shock to be stopped by the police. But for other folks, it's like, you know, you literally, you just know that when you leave your house, there's, it's just a rite of passage. Is this something that's going to happen on a regular basis? So Yeah. that inability again, to ever blend in is I think part of the experience of being you know, racialized person in so many places.

[00:35:01] Anna: I think you summed it up best with this sentence. I'll just read it. You said "The extent to which anyone can simply be in an urban space, tells us a lot about who has power, who feels their right to the city as a natural entitlement and who will always be considered out of place."

[00:35:19] Book excerpt: “Fear of crime surveys ask participants about who they fear and for women, the answer is always men. But since we have very little control over the presence of men in our environments, and can’t function in a state of constant fright, we displace some of our fear into spaces: city streets, alleyways, subway platforms, darkened sidewalks. These spaces populate our personal mental maps of safety and fear. The map is a living collage with images, words and emotions layered over our neighborhoods and travel routes. These layers come from personal experience of danger and harassment, but also media, rumors, urban myth, and the good old “common sense” that saturates any culture. The map shifts from day to night, weekday to weekend, season to season. The map is dynamic. One uncomfortable or scary moment can change it forever.”

[00:36:14] Anna: The next chapter to discuss was called the City of Fear. And this was my personal favorite chapter. Not because I enjoy the idea of women living in fear, but because it felt very validating in so many ways.

This is something that is just standard for every woman I know. And we talk about it a lot and you know, I've said in the past that I feel like we need a name for this problem, because it can feel so abstract, even though it is very real and very ubiquitous with the female experience. So can you tell us what is, what you have called the "female fear"? And are we just born with it or how has it seeped into every one of our consciousnesses, or are women just being irrational?

[00:37:01] Leslie: Well, I think you're probably hinting that I'm likely not going to say that women are irrational but unfortunately that is one of the explanations has been put out there for this idea that women are like innately or overly fearful of particularly strangers and public spaces. So, when I talk about the female fear, it's what sociologists and criminologists have described as this kind of pernicious phenomenon where when they do their fear of crime surveys and so on, women will typically report higher levels of fear of crime. And that fear of crime literally kind of takes place in public environments with strangers, even though, I think as many of us know, women are much more likely to experience violence in the home, or simply from somebody that they know than they are to experience it from strangers. So this is a conundrum, right?

Like, oh, are women being irrational because they're not properly kind of locating where the true danger to their persons are? Uh, well, no. So, so then why, right? Why. Why is this? I mean, we love to just blame it on, I don't know the hysterical uterus or something, but I think there's a much more obvious explanation, which is the socialization aspect that we've touched on a few times in this conversation, the way in which people are taught at very young ages, the ways to be that are aligned with assumptions about their gender.

And one of the common sorts of female gendered socialization is to fear strangers, to fear men, and to fear of being out in public. This is taught to us from a young age as children. I think it kind of probably for many women gets really reinforced in puberty when there's a sudden sense of, okay, now you are vulnerable because you are developing into a sexually mature adult.

And so there's that danger as well. But we also see it in so much of our popular culture, right? Whether it's all of the cop shows that we love to watch like our law and order SVU or criminal minds. Yeah. Even the true crime podcast, boom that we have right now. And, you know, I'm not, kind of panning this, I participate in partaking of this culture as well, but it's every season, the extent to which horrible violent crimes have to happen to women to kind of keep the interest happening. You know, it kind of reinforces this idea that there are serial killers around every corner, right?

That the greatest danger to women is, you know, going to be out there in the park at night, rather than unfortunately at home with your husband, which is sadly where the greatest danger lies.

[00:39:54] Anna: Yeah, you said in the book to describe this phenomenon, all these messages and instructions about stranger danger and what we do about it "comes in like an IV drip building up in our systems. So gradually that once we become aware of it, it's fully dissolved in the bloodstream."

And I think that that's a great explanation of how that happens. And to your point of the reality being that most of men's violence against women being in the home, if this is the case, how has the narrative so wildly inaccurate? And from your perspective, how does the design of our cities kind of play into that narrative?

[00:40:33] Leslie: Well at the risk of sounding like a conspiracy theorist, I think they're the reason why that narrative is so wildly inaccurate is because we need to kind of continue to uphold the status quo of the heterosexual family. And part of the reason for that is like we discussed earlier the need for women to do all of this unpaid care labor in the home.

And if we totally broke free from that form, if we decided nope, no more heterosexual marriage, no more single family home, the entire system would just crumble, right? It would just not function as it is. So we have to kind of keep selling women on the idea that safety and security comes from marriage comes from partnering with a man when unfortunately for so many women the exact opposite is true.

So what does this have to do with cities? Well, I think in some cases we continue to like maybe overly focus on safety in public spaces. Not that there shouldn't be a focus on it, but it's kind of assumed to be like, okay, cities will address the problem of like lighting and sight lines and urban design elements and things like that.

And then we'll leave domestic violence to a totally different area of social policy often to totally different levels of government. And we kind of won't connect the two problems together in terms of how we might imagine solutions to that. So partly, you know, I like to think about, yeah what are alternatives to the single family home and the household and the family, as we know it today. And can we continue to expand those options so that people don't feel like this is the only path, right, the only way to live and you know, what might that do to kind of break the hold of domestic violence over so many people?

[00:42:20] Anna: I think it's just mad how much of a toll this kind of violence takes on the economy, you know, for living in a capitalist society that is so driven by economic productivity, you think that they would mind the 23 billion pounds that it costs the state, employers and victims in England and Wales every year.

That was the stat I looked at before this. It's just wild. So there's that, cost, but then you talk about the implications of this fear on the individual woman as well, the psychic toll. Can you tell us a bit about that?

[00:42:56] Leslie: Yeah, it's that burden of all of those seemingly little things that we take on, on a day-to-day basis, you know, checking, double- checking that your phone is charged, that you have money for a cab, that you have told somebody where you're going if you're leaving the house at night, that you've planned for friends to text you in the middle of your date to make sure that you're okay, that you plan to text one another when you get home, that you look up ahead of time, the routes that you're going to travel, you memorize bus schedules, you avoid shortcuts. Like we could just go on and on and on you, you know, you think about the way that you're dressed, you think about who you'll be with, or won't be with.

And we've just been taught to believe that this is just normal, right? Like this is just a natural way of doing things, but when you really start to list them all out and again, you know, so many women are like, oh yeah, like I just thought that was normal, that was just me, or that was just what, like, no, this is basically the rules that we've been taught to live under. And I think the psychic toll is just like this low grade kind of stress that exists. You know, that sense of like, not being able to just get on the bus at the end of a long day at work. And just like truly relax, because you don't know who could potentially be around you. You have to keep your eyes open and if you don't, uh, you're likely to be blamed for something bad.

That would happen. Oh, she fell asleep on the, oh, she got up at the wrong stop. Oh, she, you know, whatever it might be, it's going to be your fault if you, if you weren't extra vigilant.

[00:44:34] Anna: Exactly. And that's why, you know, I sometimes wonder do we do all of this policing of ourselves because we think it actually works or just to cover our asses for if anything actually does happen that we can say, well, I did everything right and it still happened even though to your point, that won't matter, there'll be something else. Everything that you listed, I mean, I think we should just start listing them all off so we can all see how ridiculous that it is. I mean, I have a couple friends that told me the other day that they consciously look for street cameras when they're out so that their faces are registered on them. That's just like a reflex for them now. That was a new one that I had not considered, I'm like, oh no, should I be doing that?

[00:45:17] Leslie: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, as modern technology changes, we're sort of given all of these like new ways to police, as you say, our own behavior. Um, but to what end, right?

[00:45:28] Anna: Yeah.

[00:45:29] Leslie: Yeah.

[00:45:30] Anna: Okay. So then onto what we do about it, I want to talk about what we can do about it, but first I want to talk about what we can't do about it. Um, a lot of people believe that in order to keep people safe, and specifically women, we need more police, you know, more crime, more police. Why is that not the approach that you suggest?

[00:45:50] Leslie: Sure. Well, I think just on the face of it, if we actually looked at what policing has done to improve women's safety over decades or century, or more, like I'm just waiting for somebody to actually show me statistics that say, oh yeah, policing has helped. The criminal justice system has made the world safer for women. I just think objectively it has not, even if it is proceeding with the best of intentions, which honestly a question, but even if it was, um, it's not working, it's not doing what it says it's going to do. So I think in that sense, if we keep putting our eggs in that basket, then change isn't going to happen in at the end of the day, we're just, you know, we're just giving more money and resources to institutions themselves that are very patriarchal, are very violent even towards the women that work within those institutions, you know, the number of women, police officers, and so on that report, sexual harassment and even assault from their colleagues, right? It's a huge number. So they can't even police themselves or take care of the women that are within their own ranks.

How are they going to take care of women in public? And of course, the perhaps even more compelling argument is just that policing causes so much harm and danger to so many communities, whether that's people of color, Black and Indigenous people, queer folks, homeless folks, trans people, sex workers, poor people, that I don't think the potential safety of some small group of likely white middle-class women really justifies the danger to so many other people.

[00:47:31] Anna: Yeah, absolutely. Using that as a justification for practices that target vulnerable groups is definitely not the answer. Um, And of course, as you mentioned, police forces themselves can be a hotbed of sexual harassment and assault against the public. know, This is all really timely for us here in London, where the conversation has been more on the forefront than usual because of the recent case with Sarah Everard, who you mentioned in your book, um, maybe I'll just give a quick background for any of those who don't know her story.

She was a 33 year old woman who was walking home from a friends. She was falsely arrested by an off-duty police officer who showed her his police ID, told her she was breaking COVID curfew, handcuffed her, put her in his car and then drove her off to a field where he raped and murdered her. And, you know, this is just, it's so evident how pervasive the culture is because this police officer who, you know, was a police officer, despite the Met trying very hard to distance themselves from him, he had been reported for multiple indecent exposure events, one of which was just days before Sarah was murdered. And he was literally nicknamed the rapist by his colleagues and was known for making his female colleagues uncomfortable. And yet, it seems that it's on women to fix the problem. The Met and the government are doing nothing to address the culture and the systemic issues and instead are doling out advice for what women can do. Have you seen any of the advice that they're giving to women?

[00:49:09] Leslie: O yeah, the senior officer who said, uh, you should, you know, question any officer who approaches and tries to arrest you, you should ask them to call another police officer to verify there, I mean, can you imagine being, for example, a black woman on the street, try, I mean, even for a white woman, I think you would, you know, quickly test somebody's patience, right. But I mean the obliviousness to the power imbalances there is stunning.

[00:49:37] Anna: Yeah, it really is. It's again, don't fix the system, fix the women. They said you can, this is in quotes, "shout or wave a bus down if you don't trust the male officer". Okay.

[00:49:51] Leslie: Yeah. I know how those London buses roll through the streets. Not stopping. They barely stopped for you at the stop. Let alone...

[00:49:59] Anna: Yeah, yeah. Not at a stop. And then the officer is just gonna stand there and let you do that. Of course. Um, but then also this got a lot of attention because it was terribly gruesome, but also because she was white and middle-class, and as you point out all too often, these victims are ignored because they're Black, Indigenous or trans women, which was a case in point with another London case of Sabina Nessa, who was a woman of color who was murdered like six months after and the media coverage was vastly different.

So about what we can do about it then, firstly, on an individual level, you've said that we've essentially given the same advice to women for 150 years about what she can do, except for now we're saying, well, also carry your phone. And that instead we should flip the script and stop asking what women can do and start asking what men can do. So what can men do, Leslie, do you have any thoughts on that?

[00:50:57] Leslie: Yeah, I mean, to start with, men can, learn, first of all, I think many men are oblivious to, you know, all of those things that women do on a day-to-day basis to attempt to look after their own safety. So maybe learn about that. Talk to the women in your life about kind of what it's like for them.

Try to step into their shoes for a moment, right, to recognize that what they're doing is not irrational, but it's built upon lifetimes of socialization and so on. And then think about what can you do to change your behavior? There's likely things that many men do that they think are very innocuous, whether it's telling someone to smile, speaking to them when they're wearing headphones or not wearing headphones, you know, maybe just pay attention to your own behavior throughout the day and think about in what ways am I acting that might be making somebody else uncomfortable here. But perhaps, even more importantly is that, men need to kind of check other men, right? Like you cannot let it slide. When you hear somebody making a cat call, when you hear people making racist and sexist jokes. When people are talking about picking up drunk girls at the club, you need to shut it down because I think women have been talking about this for decades, if not centuries. You're not listening to us, right, maybe you will listen to each other. So if you're not kind of stepping up and doing that work, then even if you are a quote unquote, a good guy, I think you're still part of the problem if you're allowing the culture to just make it a toxic way downstream for the next generation.

[00:52:35] Anna: Yeah, I think that's a really good point. There was all kinds of stuff going around on social media after Sarah's murder about what men can do- walking on the other side of the street, you know, don't walk closely behind, but exactly, as you say, it's not just about you, yourself. It's about what you do in situations when you see other people maybe behaving as you know that they shouldn't be. And then I know this isn't a fixed the woman situation, but is there anything that we can personally do to try to alleviate the female fear? You know, at least as a coping mechanism until the system has fixed.

[00:53:14] Leslie: I think, you know, as much as it's sometimes frustrating the sort of you know, go out with other women, travel in groups, that sort of thing. It's frustrating when it's advice that's kind of being pushed on us, but I think we can also recast it and recognize that there are ways that women have long taken care of each other.

Right. And that when we do text each other. When we get home, when we do offer to walk a friend home, when we say we're going to go together to do this thing. It is an expression of collective care. It's a way that we look out for one another, given the knowledge that we know that actually, maybe the police are not really going to be there to help us or that we can't rely on strangers to look out for one another.

So I think one thing that women can do is yeah, take care of your friends, even take care of strangers, maybe participate in learning about bystander intervention. Things that you might be able to do should you witness something happening that you think is problematic. So, let's not discard those things that I think women have been doing for so long, just because they sometimes come with this like patriarchal baggage, but can see some of them as actually empowering. Things that we do for one another that are kind of outside the system of what, what we've been told to do.

[00:54:32] Anna: Yeah. And, um, I guess do you think that this can also be applied to women everywhere, suburbs elsewhere, you know, you have the empty gas stations or parking lots, is there a suburb version of the female fear? Do you think all of this kind of applies, outside as well?

[00:54:49] Leslie: Yeah. I mean, probably even worse in those sorts of environments, because one of the things that makes people feel safer is when there are other people around. When they're open businesses, when there's a traffic going by when, when there's a sense of liveliness to the street, so suburban environments and so on can be even more frightening.

I'm not entirely sure what the immediate solution is except to keep thinking about building more mixed use environments, integrating residential and commercial spaces, having more public transportation through those neighborhoods. These would be at least a few steps that could be taken in those areas.

[00:55:27] Overdub: “And now for: “men are losers too”... in gender inequality of course. These are not "women's" issues, these are everyone's issues, because as long as women are held back from their full potential, so are we all.”

[00:55:42] Anna: So we've talked a little bit about this throughout, and we know it's not just a woman's issue, but society as a whole gets to benefit when women are allowed to participate fully. So why is including men in this conversation important and what do they stand to gain in a more feminist city?

[00:55:59] Leslie: Sure. Well, I think that men's lives in many ways are constrained by the ideals of toxic masculinity or traditional masculinity that don't allow them to really fully express themselves as human beings in terms of their emotions, their desires, their sexuality, their caregiving capabilities, all of these things are kind of shuttered and pushed aside under traditional ideas of what it means to be a man. So I think opening that up is, is of benefit to men being able to more fully participate in all of the ways of being human without being so limited I think what would be a good thing for many, and of course, you know, recognizing that not all men experience all of these forms of privilege, right?

And there are many men who experienced forms of violence and discrimination and inequality in urban life and a lot of the things that we're talking about about creating generally more safer cities, more affordable cities, more accessible cities will be a benefit to many men as well.

[00:57:05] Book excerpt: "The feminist city doesn’t need a blueprint to make it real. I don’t want a feminist super planner to tear everything down and start again. But once we begin to see how the city is set up to sustain a particular way of organizing society across gender, race, sexuality and more, we can start to look for new possibilities. There are different ways of using the urban spaces we have. There are endless options for creating alternative spaces. There are little feminist cities sprouting up in neighborhoods all over the place, if we can only learn to recognize and nurture them. The feminist city is an aspirational project, one without a masterplan that in fact resists the lure of mastery. The feminist city is an ongoing experiment in living differently, living better, and living more justly in an urban world."

[00:58:01] Anna: Great. And then for the City of Possibilities and the alternatives. What does a feminist city look like? And do you have any examples of what other cities are doing well?

[00:58:15] Leslie: Yeah. I think one of the primary values that a feminist city would express would be this acknowledgement of the importance of caregiving work and of not only making women's lives easier, but actually trying to figure out ways to share and collectivize that work. I think there are a lot of examples of kind of the former happening, where there are urban efforts to make juggling care work and paid work a little bit easier.

So, cities that include, you know, gender mainstreaming in their urban plans are looking at the ways in which transportation routes, snowplows schedules, school mobility plans, and so on impact women and men differently and trying to make sure that they are not kind of reproducing gendered inequalities in the way that they design spaces.

So cities like Vienna have long had gender mainstreaming as part of their agenda. Barcelona is another example where especially at the moment, they have a lot of female leadership in that city and they are really pushing for more pedestrian spaces, more green spaces, more active mobility, safety for children on the streets, all of these kinds of things that really make them more like human kind of everyday urban environment.

In terms of going that step further and figuring out how do we really like collectivize this labor? I'm not sure that there's a ton of that that's coming from the top, if you will. I think that's more coming at the community level. If we look at mutual aid organizations and so on that are really about trying to create networks of care that are not dependent on the state or charity or things like that and are not assuming that there are some people who are needy and some people who are not, but that we all need care. We all have things to offer. I think we could probably learn a lot from those examples and see if there are ways to kind of integrate them into the City of Possibility, of the future.

[01:00:14] Anna: The City of Possibility, I love that. So are there any really easy and maybe more affordable things that cities can do or take as a first action?

[01:00:28] Leslie: You know, I never thought I would be talking so much about restrooms when I wrote book, but it comes up again and again, and I do think, you know, it's not free to provide public restrooms, I realize that, but it's also not that complicated a thing that cities could do or that they could kind of revive. So in my hometown, Toronto, there are public restrooms in parks, but they are all shut down for the winter because they're not heated spaces. So what could we do to change that, right, to make kind of a year round accessibility. What would make those spaces safer? What would keep them cleaner?

Right, this does require some investment, but it doesn't require, bulldozers and decades of construction and a trillion dollar infrastructure bill, right, it just requires a little bit more in the budget of already a billion dollar city budget, like maybe take a little from the police and put it into public restrooms.

That's just one idea. Right. Um, and something that, that would make a big difference, not just for women, but, during COVID we've been told you to go outside and socialize oh, sure, until you need the bathroom, and then what are you going to do? So it could do a lot to kind of revitalize public space, make it more tourist friendly if that's one of your goals, great for children, great for seniors, all sorts of people who typically, maybe are limited by lack of toilet access.

[01:01:53] Anna: Yeah. And I mean that just another point of something that everyone will benefit from, including men as well. So...

[01:02:01] Leslie: Absolutely, yep.

[01:02:02] Anna: Everybody uses the bathroom.

[01:02:06] Overdub: “Just a quick note to say that this is by no means a trivial issue, especially when you look at the global picture. In Leslie’s book, she writes that the lack of safe facilities for women and girls put them at even greater risk of violence. And that an estimated 2.5 billion people globally lack access to proper sanitation. United Nations has recognized sanitation as both a women’s rights issues and a human rights issue, but little progress has been made on this particular development goal.”

And then is there anything that we can do as individuals to help create this City of Possibilities? This feminist city.

[01:02:50] Leslie: Yeah. I think, It can be small things, right, it doesn't have to be, oh, I'm going to run for mayor and change everything. It could be being that bystander who notices and says something when something is going wrong. It can be the person who checks on an elderly neighbor, make sure that they have something to eat or that they have a ride to their doctor's appointment. It can be, hanging a pride flag outside of your house during pride month or maybe all year. Right? It can be those kinds of like symbolic gestures, you know, the black lives matter flag or placard, things that signal your political and moral and ethical commitments in the world. And the one where people kind of see that and recognize one another in those intentions, you know, that's great. You can go and join a protest. You don't necessarily have to organize the protest, but you can join a protest if that is available to you or safe for you. It never hurts to have that one extra body you might think, oh, I don't make a difference, but you know what, if everybody thought that and everybody stayed there. We would never have protests and, and they do lead to change. It's not always overnight, but it's important. It does matter. So if you can get yourself out there on the street every once in a while, go for it.

[01:04:09] Anna: And they can also get your book to keep learning more on this.

[01:04:12] Leslie: That's always an option too. And, yeah, I won't dissuade you from that choice.

[01:04:18] Anna: All right, one more question. And then we'll get into the final section. So if people take one thing away from this conversation today, what do you want it to be?

[01:04:28] Leslie: That a different city is possible. We tend to look around at the built environment and think it's always been this way. It's kind of unchangeable. It literally is stone and concrete. It's not mutable, but there are so many systems and processes and just ways of being in the city that are not so fixed, right? That don't require a bulldozer or a crane or a wrecking ball to change them. The way that we live in cities, the way that we relate to one another, the way that we use spaces, those can all be changed. It's always dynamic. So don't feel trapped in the city that we have. There's a possibility in every corner of the environment.

[01:05:12] Anna: Beautiful.

[01:05:14] Overdub: And now for: “Your Story”, the part where you are invited to reflect on this story as it relates to your own life - think about it, write about it, talk about it, and if you wish, share with the community. Whether or not you are listening in real-time, if you send in your thoughts, experiences, questions, and recommendations, they may be included in a future listener-led episode. Check out the link in the show notes, or revisit the Your Story episode, to learn more. Remember, no matter your story, you are not alone in your experience, and there is power in our collective realisation of this.

[01:05:57] Anna: All right. So as listeners come away from this hour with you, are there any questions that you want to put forth to them? What can they pay attention to as they go about their lives? Are there ways they can reflect on their own experiences or ideas or organizations that you would like to hear more about?

[01:06:15] Leslie: Definitely. I think people could start the kind of practice of noticing things a little bit differently. So they might ask themselves, you know, what experiences have you had that have maybe led you to question whether you truly belong in a space? Have you ever been made to feel like you don't belong? In what ways have you had to improvise to make the city work for you? So that might mean like, oh, I had to turn a bench into a changing table for my baby. Right. Uh, we sometimes have to like work around the barriers of the city. So that's always an interesting thing to think about, right? Like what ways do you challenge the built environment as it is?

Maybe I would always be interested to know what changes to the built environment, big changes or little changes, do people think would make the biggest difference in their day to day life? Maybe it would be getting rid of the stairs outside the public library, or maybe it would be, um, a totally free and fully accessible public transportation system. But what in your life or in your city would change that would actually make your day-to-day life easier, safer, more affordable, anything like that?

[01:07:31] Anna: Excellent questions.

[01:07:35] Overdub: And now for: the “feminism gets a bad wrap because the narrative has been just a bit one-sided" corner.

[01:07:43] Anna: All right. And now for some rapid fire questions to wrap up. Leslie Kern, what does feminism mean to you?

[01:07:53] Leslie: Well, I'm going to borrow a bit from Bell Hooks and say that that, to me, it means a ongoing intersectional movement toward the end of gender and other hierarchies.

[01:08:05] Anna: Have you always been a feminist?

[01:08:07] Leslie: At least since I was a teenager, for sure.

[01:08:10] Anna: All right. What is one of your earliest feminist memories, or a time when you realized the world didn't treat girls and boys the same?

[01:08:19] Leslie: Well, I recall that I wrote a college admissions essay that was called something like, "God must be a man", where I argued that only a man would create such an unequal world.

[01:08:30] Anna: Um, and what is the Story of Woman to you?

[01:08:36] Leslie: I would say it's a story of struggle and perseverance, but also kind of collective wisdom and care.

[01:08:44] Anna: Love it. And a few more, what are you reading right now?

[01:08:48] Leslie: I'm reading a psychological mystery called Blue Monday by Nikki French.

[01:08:54] Anna: Ooh, intriguing all time favorite book?

[01:08:58] Leslie: Well, it's hard to choose a favorite but a book.

that I've read many times and probably will read many times again, is Written on the Body by Jeanette Winterson.

[01:09:08] Anna: Ooh, I'm going to have to look that one up. These will all be in the show notes as well, by the way. Um, who should I make sure to have on the podcast? And it's okay to be aspirational.

[01:09:19] Leslie: Oh, great question. Well, I read her book earlier this year, Feminism Interrupted by Lola Olufemi and, uh, she's a fantastic speaker, someone who I think would really have a lot to say about what women can do to create a feminist world without relying, for example, on the state to make it happen for them.

[01:09:42] Anna: I think that's a sign because I bought that book on Saturday. So...

[01:09:45] Leslie: there you go. Yeah, it's a great read.

[01:09:47] Anna: Lola, I'm coming for ya. Um, what are you working on now?

[01:09:52] Leslie: I just finished writing my next book, which is all about gentrification and that will be coming out next fall from Verso and Between the Lines. And I'm also working on a book about feminism in academia, a kind of how to make your academic work environment a more feminist space.

[01:10:12] Anna: Oh, very nice. I think a lot of people need to read that one when it comes out. And then where can we find you? This will be in the show notes and on our website as well, but where can people find you?

[01:10:23] Leslie: Sure I am at LellyK on Twitter, Instagram, and, uh, on Peloton, if that's your thing as well.

[01:10:32] Anna: Oh, love it. I need to get one of those. Amazing, thank you so much, Leslie, for your time. Author of Feminist City, everybody go out, get your copies. There'll be a link in the show notes and on the website, but really appreciate your time here with us today.

[01:10:51] Leslie: Thank you for having me. It was great to chat with you.

[01:10:54] Overdub: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one-woman operation, with some editing help from Clare Mansell and voiceovers done by Jenny Sudborough. If you enjoyed this episode, there are a few small things you can do that make a big difference in helping other people find the podcast and allowing me to continue putting out new episodes!

You can subscribe, leave a review, share with a friend, follow us on social, buy me coffee (not literally - this is the name of the platform to raise production funds - but hey, I’d grab a coffee as well), or head to the website and check out the bookstore filled with 100's of books like this one. If you purchase any book through the links on the website, you support this podcast - and local bookstores! Soooo feel free to do all your book shopping there! All of these options are in the show notes.

Anything you can do is appreciated and makes a big difference in elevating woman from the footnotes of history to the main narrative.

💌 Sharing is caring