[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Overdub: Hello, welcome to The Story of Woman, the podcast exploring what a man-made world looks like when we see it through her eyes. Woman's perspective is missing from our understanding of the world. This podcast is on a mission to change that. I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein Lau and each episode I'll be speaking with an author about the implications of her absence - how we got here, what still needs to be changed, and how telling her story will improve everyone's next chapter.

[00:00:34] Section: Episode level introduction

[00:00:35] Overdub: Hello welcome friends - thank you so much for being here! Did you know that the average person concerned about becoming pregnant spends about thirty years trying not to get pregnant? And people do so mainly by using prescription birth control which is seen, and taken for granted as natural and beneficial, and of course, a woman’s duty

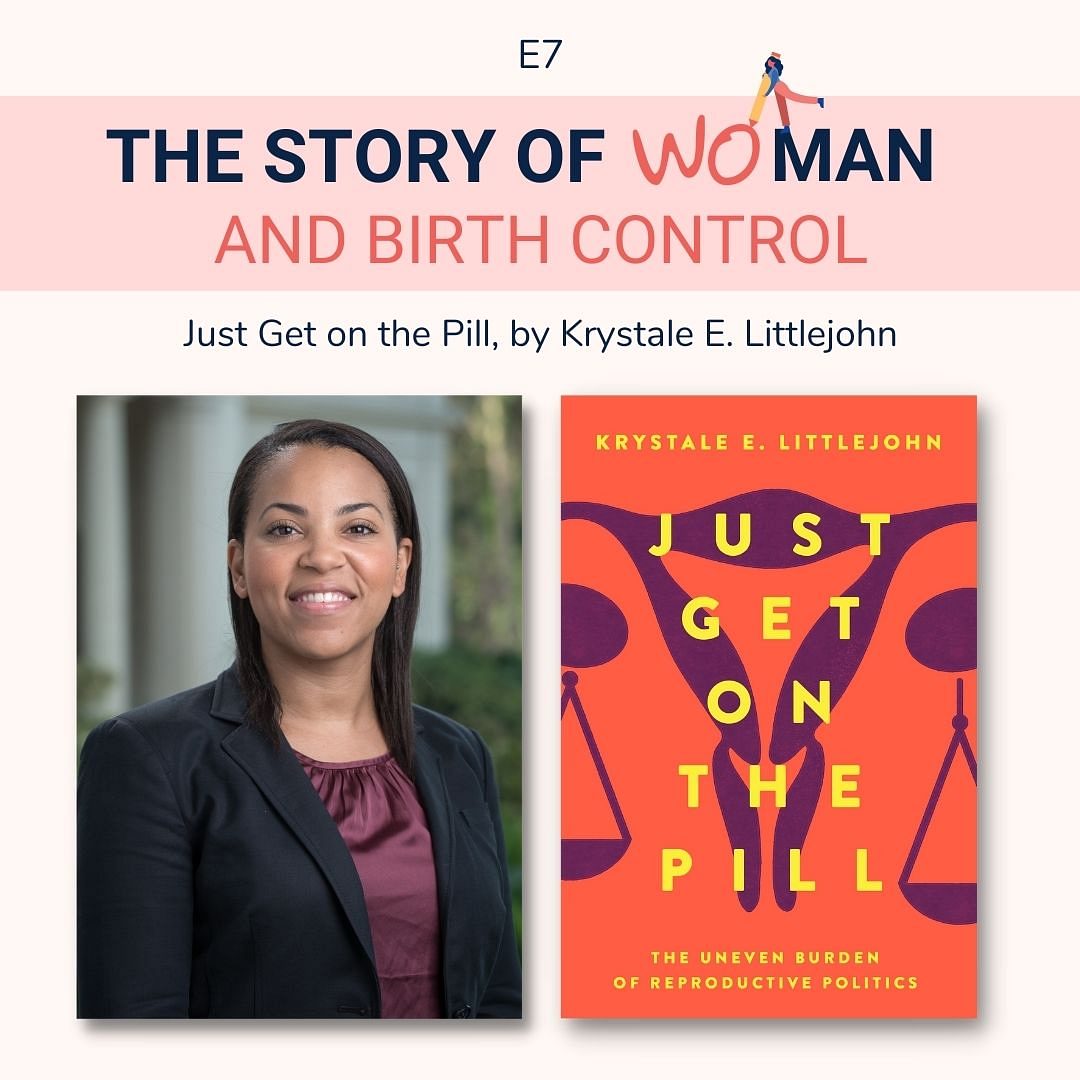

My guest today breaks this down with extensive research where she looks at how birth control is a fundamentally unbalanced and gendered responsibility. She argues that this gendered approach encroaches on reproductive & bodily autonomy and makes it difficult to prevent disease. I am speaking with Dr Krystale Littlejohn, author of the very aptly named book, Just Get on the Pill. Dr Krystale is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Oregon. She earned her Ph.D. from Stanford, and was a sociology and Spanish language & culture double-major at Occidental. Her work examines race, gender, and reproduction, as well as theorising the social underpinnings of fundamental life processes that are often taken for granted as natural.... such a just getting on the pill!

In our conversation today, Dr Krystale and I talk about how society’s ideas about gender help explain the phenomenon of what Dr Krystale calls gendered compulsory birth control and the need to see pregnancy prevention as *yet* another form of domestic labor. We talk about the importance of language and the need to get rid of words like male and female condoms, and also stealthing... which should really just be called sexual assault. We talk about larger societal issues like how poor women are blamed for *causing* unintended pregnancies instead of recognising that poverty is a reason people might label their pregnancies as undesired in the first place. And also how women's fertility is often seen as a tool for solving a variety of social problems.

And we talk about side effects... like weight gain and low libido... but also blood clots, something that really gets me going as you may notice in the interview... and i even had to cut out a slight tangent that i went on about how here in the UK and the EU, the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine was suspended at one point and the rules changed for who could get the vaccine because of the risks of blood clots.

And the irony of course, is that the risk of blood clots for hormonal birth control pills is higher than the risk from the vaccine. But of course, no one considers revisiting or doing anything about that and we continue to tell women not to worry, and to just get on the pill anyway. And we talk about what a more liberating approach to birth control looks like and what steps we can take as a society to get there. So we talk about a lot...which is why this episode is a little lengthy but Dr Krystale had so much fantastic wisdom to impart on us that I just had to include almost all of it!

And as always, the quotes you will hear read during the interview are taken directly from the book Just Get on the Pill

If you like what you hear today and you want more people to recognise the uneven burden of reproductive politics, feel free to share the episode with someone. But for now, sit back and enjoy my conversation with Dr Krystale Littlejohn

[00:04:20] Section: Episode interview

[00:04:21] Anna: Hi, Dr. Krystale, welcome. Thank you so much for being here.

[00:04:26] Krystale: Thank you so much for having me.

[00:04:27] Anna: I'm super excited to chat with you today and I would love to start by having you kind of set the framework for us and helping us understand the main arguments of your book, and then we'll get into them in more detail. But what exactly is the problem with how things are currently done when it comes to different methods of birth control?

[00:04:49] Krystale: The problem is that we have an uneven social approach to birth control, where we put all of the pressure on women and people can get pregnant to do all the work, to prevent pregnancy, and we completely leave their partners out of the equation. And so Just Get on the Pill, it takes a look at that, right? I examine what is going on with birth control? How are people organizing birth control in their relationships and what are the consequences of this organization? And I find that birth control use is incredibly gendered, where we expect women and people can get pregnant to do all of the work, and we let their partners off of the hook.

We rarely acknowledge that they too are responsible and play a role in preventing pregnancy and in conception. And so the book tells a story of just over 100 young women . As they're navigating sex with their partners. And it tells the stories of the trials that they face trying to prevent pregnancy because of a gendered approach that single-mindedly focuses only on them.

And I show that despite the knowledge of birth control methods and the different birth control methods that are available out there for women and despite the availability of condoms, that women are pressured to use only methods made for their bodies, despite their frustrations. And this ends up having a whole host of negative consequences, not only for their ability to prevent pregnancy, but also for their ability to protect themselves from disease and to fully have control over their body.

[00:06:14] Anna: And like I said, we will get in to all of that, but I also want to address that this might sound counter-intuitive to some people, you know, right off the bat, because we have been taught to see birth control as this liberating tool that's allowed women to plan their pregnancies and in turn, get an education, focus on their careers, or even opt out of having children altogether. So I'm sure we'll discover this more as we get into our question and answers, but can you just help us reconcile these two seemingly opposing ideas?

[00:06:48] Krystale: Absolutely. So the key for me is that birth control can't be liberating when people don't feel like they have the freedom to choose it. And so the central question that I ask is under what conditions can birth control be liberating and under what conditions is birth control liberating? And so when a person wants to rent pregnancy and they have the information to do so, and they feel supported it in making a decision that feels right for them, that is a liberatory approach to birth control, right? That's a liberatory experience of birth control, but when a person is maybe interested in understanding the methods that are available for them, maybe trying those methods, uh, but maybe not and they have partners or families that pressure them into, like I said, single-mindedly doing all the work without any consideration of their needs, right. That is not a liberatory approach to birth control. And I think we could all agree that if a person is being pressured to use birth control, when they don't necessarily want to use a prescription form of birth control or when they want their partners to use condoms right to protect both of them, that's, that's not liberating, right? It's not liberating to feel coerced into doing something. And so for me, the real emphasis is on centering the needs of the person and asking ourselves is our approach meeting their needs. Right. If our approach is meeting their needs, then that could be a liberatory approach to birth control. But if it's not and it oftentimes involves coercion, like my research shows, right. That's not liberating at all.

[00:08:13] Anna: That's so true, how liberating can it be when a choice not to use something is treated as irresponsible or selfish. I mean, what choices do you really have exactly, as you say within that context. So it's a really great way of reframing that question and that conversation. So to look at this, from an individual perspective, and then we'll get into kind of the wider social perspective, what are some of the common behaviors and experiences amongst the women who participated in your study? And maybe you can just give us a brief background . About the study itself.

[00:08:51] Krystale: Yeah. So this study, a research team that I was a part of interviewed over 100 young women in the San Francisco bay area. And we're really interested in understanding their experiences with sex, their experiences with birth control, their experiences with side effects and pregnancy. And the key for us was to be able to understand what happens in these young women's lives, right? What helps them be able to prevent pregnancy when they're looking forward to doing that or why don't they use birth control when they aren't interested in getting pregnant?

And so the most common experience that I found, and this is consistent with the research is that women overwhelmingly had used some form of prescription birth control. Right. They had used the pill, the shot, the intrauterine device, the implant, right? So they had overwhelmingly used one of those methods at some point in their lives. Many of them had been taught that that's what they should do. That's where the name of my book comes from. Right. Just Get on the Pill comes from people being told, oh, you should just get on the pill. Oh, your boyfriend or your partner is giving you trouble with using condoms. Oh, you should just get on the pill. And that is the solution to having these challenges. And so the key things where they had ever used a form of prescription birth control, overwhelmingly, many of them had experienced side effects and those side effects created a great deal of frustrations for them and made it difficult for them to use the birth control like they want it to, and they also experienced challenges with their partners, right? Challenges, getting their partners to use condoms like they want it to and challenges not having their partners make them feel pressured to get on a form of prescription birth control, if that wasn't necessarily what they wanted to do.

And I'm talking about partners here, but the key point of the book is that young women are socialized to use prescription birth control methods as their method, by not only by partners, but also by parents, by friends and by medical providers. And that goes a long way toward explaining why we see these uneven patterns of birth control use, where it's largely women and people who can get pregnant, who are preventing pregnancies.

[00:10:51] Anna: I think you called it the "gendered compulsory birth control" was the term for this, shall we say phenomenon of or coercion, probably.

[00:11:00] Krystale: Right. Spot on. Spot on.

[00:11:02] Anna: And you, you had speaking of healthcare providers, you know, it's parents, friends, partner, schools, and healthcare providers that are putting this pressure on, you had an incredible example in the book where a woman had just broken up with her boyfriend and went to her gynecologist to talk about getting off the pill because of hormones and the gynecologist told her something like, you know, Gina, if you wake up tomorrow and prince charming on a white horse comes to pick you up, what are you going to do without birth control pills, you must stay on birth control pills, essentially because of this hypothetical prince charming,

[00:11:37] Krystale: Right! And I think I, you know, I'm so glad that you're bringing up Gina because Gina's experience and telling Gina story is one of my favorite parts of the book, even as it's a kind of heartbreaking experience from the perspective of trying to be mindful of women's needs and their right to use or not use birth control and so in this case, what I think is fascinating is that the expectation is that prince charming, who's going to come along tomorrow, is a man who doesn't want to wear condoms. Right. And it's just this fascinating theme that in whose world is prince charming, this person that you just met, who's coming along and doesn't want to wear condoms.

And your job as a woman is to anticipate that and to stay on birth control pills so that he can have his desire met right, when it comes to not using condoms. And so I just think it's fascinating, not only in the sense of gender compulsory birth control as the concept that I introduced, but also in the sense of just the gendering of domestic labor in the sense of centering men's needs over women's needs and desires in health and lots of other areas.

And so I'm, I'm so glad that you brought that up because I think it really isolates the need for us to think very carefully and critically about what our approach does and what it means. But most importantly, what messages it communicates to young women and women in general about what they should expect and what they should be prepared to tolerate.

[00:13:02] Anna: That's so true. You just assume that that is your job because prince charming won't want to wear a condom, so you better make sure that he still enjoys himself. And another term, domestic labor, which you just mentioned the kind of laboring, and that was a new idea for me, but makes complete sense. Could you walk us through that? You know, why do you consider it domestic labour?

[00:13:25] Krystale: Yeah. So I think the key for me is even though it's overlooked, as a form of domestic labor, preventing pregnancy falls along the same kind of spectrum that we see domestic labor operating in other contexts. So when it comes to housework, for example, right, the idea is that having clean dishes, benefits both partners, right. And we expect that we don't say it's fair that the woman does all work, taking care of the dishes, even though she benefits from being able to have clean dishes, right. We recognize that there should be some expectation that her partner also contribute to that household task.

But when it comes to preventing pregnancy, I think there's this understanding that it is the woman's job to make sure that a pregnancy doesn't happen. And so we kind of let men and people who can get others pregnant off the hook for doing their part to help prevent a pregnancy. And I think the key part of domestic labor comes in here because even though it is the woman's body right, my book is about the right to bodily autonomy. The key here is also that in calling on men to wear condoms, that is also a woman's right to expect that she has sex under the conditions, that meet her needs. And if she wants a partner to wear condoms, it's her right as another part of bodily autonomy to have her partner do that when he's interacting with her body. And so when it comes to this notion of domestic labor, I see contraceptive use as just one more of those things, because it entails a great deal of work on women's part that goes overlooked. They're the ones that have to figure out how to get their birth control, when to go to their appointment. They're the ones that have to deal with side effects if they're experiencing that. There is some cost involved in using birth control, not just financial costs, obviously, right? There's some costs using birth control and that is overwhelmingly placed on women. And that's a key part of why I see this as just one more form of domestic labor. Right. They're doing work that benefits the couple. But it's framed as something that is only beneficial for women.

[00:15:29] Anna: And the labor isn't short-lived, you say in the book that the average heterosexual woman will spend approximately 30 years trying to prevent pregnancy. So, uh, this is not short lived, domestic labor

[00:15:43] Krystale: Not at all.

[00:15:45] Anna: And speaking of uneven, I've read a few of these types of stats lately floating around on the internet. You know, that say one man can impregnate like nine women, every day, but a woman could only get pregnant in that specific 12 to 48 hour ovulation period every month. And I just saw another one yesterday that was like, if a woman has sex with a hundred random men in a year, she can probably only produce one full-term pregnancy. But if a man has sex with a hundred random women in a year, he can produce a hundred full-term pregnancies. So, you know, with all of that in mind, I just find it even more unfathomable that we're always talking about regulating the women. Like even if you just look at the hard statistics of who is the most likely to be able to impregnate or be impregnated, it's just still, yeah, I guess I'll leave it at that to see if you have anything to add, but then I'm also curious to move on to why is it that we see this as the natural way, you know, because women are the ones with uteruses and they're the ones carrying the pregnancy, so they should also be the ones to stop them?

[00:17:00] Krystale: That really highlights the insidiousness of gender inequality. Right. That even when you have these clearly illogical explanations for what's happening,

[00:17:11] Anna: Illogical, that's the word.

[00:17:13] Krystale: It's illogical. But even when it's illogical, we're still like, well, it makes sense that we put all of this pressure on women to prevent pregnancy because men could impregnate a hundred women. Right. It's like, that doesn't make sense. That just doesn't make sense to put it kindly. And I think that because it is just so ingrained, right, we just kind of go with the flow and it's like, yeah, it does make sense to make sure that all of these women are on birth control so that we can help all of them not get pregnant when you have this person that's out there and can impregnate all of them.

And I think it also just really speaks to these myths that we have about men sexuality, right. That they're out there, they can't control themselves. Right. They just have this need to have sex. Maybe they have a need to want to impregnate women. And for that reason, right. It makes more sense from this perspective to really socialize women into using prescription birth control methods, prevent pregnancy. But the reality is that there's no reason why we have to have this uneven approach to birth control. And if we did want to uphold an uneven approach to birth control, given this perspective, it would make more sense, right, to put the pressure on men, and people can get others pregnant, given what you just said. But as you mentioned, that's not what we see. Instead we see these statistics and these calls for women and people who can get pregnant to do all of the work because on this idea that men can impregnate so many women but as we just went through this conversation, right, it doesn't, it doesn't make

[00:18:42] Anna: So ironic. And then women don't just get the burden, but they also get the blame. There were multiple instances in your book of a woman blaming herself, you know, when she did become pregnant, unintentionally and saying it was her fault, even when it resulted after her partner refused to work condom or cooperate with her efforts to prevent a pregnancy.

[00:19:09] Krystale: Yes. And I think that is one of the more heartbreaking sides of this story, right? That because women don't feel supported in making choices that feel right for their bodies because they're not supported in saying, hey, their partners should be accountable for helping prevent pregnancy too. They end up blaming themselves when a pregnancy occurs, even in cases where they did everything that they could to try and prevent a pregnancy. Or even in cases where getting prescription birth control was just really hard.

And it really just gets at this idea that women are not provided with the support that they deserve, not only to make the choices that they want to make. But also to help them reconcile a pregnancy when it occurs and they tried their best to prevent it, but instead, still feel like they deserve the blame, when it happens and to make sure I'm being perfectly clear.

I'm not saying that we should be blaming women for pregnancy period. Right? That's that? I want to make sure that nobody's confused about that. Right? If you read my book, you'll be clear that it's not my argument whatsoever, but I think, especially in this context, right, I just want to highlight the shame that happens, right? The shame that people experience when they have a pregnancy, and they're taught that it was their job to prevent it. And so when a pregnancy happens, right, they failed at doing their job and they're a bad person for experiencing it. And it's all related to gender inequality, to denying women, and people don't get pregnant bodily autonomy, and to upholding these insidious ideas about gender that support this kind of behaviour.

[00:20:41] Anna: Mm. Yes. What are some of the insidious ideas about gender that kind of underlie all of this, would you say?

[00:20:50] Krystale: I think you, you hit it on, you hit the nail on the head when you asked the question about domestic labor. Right? So I think one of the insidious ideas that we completely take for granted is that women are responsible period. Right? And we have that idea across the board, right? Women are responsible for the housework. Women are responsible for childcare. Women are responsible for managing other people's needs and emotions. Right? And so this is just one more area where we apply that logic and. Well, women are responsible, right? It is your job to make sure pregnancy doesn't happen. Just like it is your job to make sure that the dishes are clean at the end of the day, right. That the children are fed, if there are children involved. If there's a blow up at work, what did the woman do to make sure that she appropriately managed her emotions so that she didn't respond in a negative way and then get labeled as angry. Right. So there's all of these ways and it might seem strange to be making these parallels, right in the workplace, right in the house. But this is all part of this larger gendered umbrella where our ideas about gender are not just isolated in one particular domain, right. They're diffused, they're spread throughout our society. And then we just kind of draw on them when we need to, to make sense of things and to help us understand how we should approach different behaviors.

But the key is that they are ideas about gender, the facts about gender, right? It's not the case that women have to be responsible in these ways. We just take for granted that they should be responsible and then we expect them to behave accordingly. And I should also add that as I talk about in the book, I talk about my experience too, is being a person, right, whose has to deal with these things. It's not just about them. Right. And as a researcher, as a feminist researcher, my book, isn't only about them making assumptions about what people should do. It's also about us making assumptions about what we should do ourselves. And it's all related to these larger gender ideas that we all draw from.

[00:22:50] Anna: That's great point. It's women doing it to ourselves, to other women, just as much as anyone because we are raised and live in the same system that have the same, I like what you said, ideas about gender, not facts about gender.

[00:23:05] Book excerpt: “People are socialized into gendered bodies at young ages, and social framings of birth control serve as one more tool to teach people how to think about their bodies and behavior. Teaching people to behave according to standards expected of their gender (gender socialization) includes communicating expectations that girls should be moral and chaste, boys should seek sex for pleasure and status, and young girls should be especially careful to avoid pregnancy. Through gender socialization, girls also learn they must act as sexual ‘gatekeepers.’ These are more or less well-known gender norms dictating what people should and should not do sexually.”

[00:23:45] Anna: So on the gendering front, you pointed something out in the book that seems so obvious, but I never thought of before, and that is his condoms and her birth control. So can you walk us through that delineation and why is that problematic, thinking that way?

[00:24:11] Krystale: There was this fascinating perception that reflects broader social understandings of condoms, that the condom was for the man. Right, and so over and over and over young women talked about how they didn't have to worry about condoms, in terms of buying condoms, because that was their partner's job. I remember asking one woman like how she learned to use the condom. And she laughed and said, you know, that she didn't worry about it. That wasn't her problem. Right. It was her partner's problem to worry about how to use the condom. And so there was this understanding that men were responsible for getting condoms, putting on condoms, using condoms correctly. And that women's job was to make sure that they were using a prescription form of birth control.

And the way this played out was really clear in interviews when women talked about learning about birth control methods and having their parents, help them figure out what to do with birth control. So they would oftentimes talk about parents teaching them to get on the pill, taking them to health centers to get a pill or to get another form of birth control, and not having the same kind of active involvement around condom use. And if you think about our commercials, right, our commercials around condoms are geared toward men, right?

This is all part of this broader social approach to birth. And so it's all of these messages that then end up teaching women, and teaching their partners, that a condom is for men, it's the man's job to worry about. And that prescription birth control was for women. And this ended up having negative consequences for women and their partners, frankly, because they not only had more trouble protecting themselves from pregnancy, they also could have trouble protecting themselves from disease because they were taught not to worry about condoms.

And so if a partner say they weren't saying, well, we'll even bracket prescription birth control, right? If we're just talking about disease and the negative consequences, they could be heading to an encounter with a partner and expecting him to provide a condom. And because of gendered ideas about it being his condom, they didn't bring a condom of their own. And then they get into this encounter and realize that their partner, in fact, didn't have a condom or told them that he didn't have a condom. And then they were faced with a choice. Do they continue to have sex without a condom? Or do they say, no, they're not going to have sex until somebody provides one.

And sometimes they passed and said, no, they weren't going to have sex. But there were lots of other times where they went ahead and had sex without a condom, simply because a condom wasn't available. And simply in part, because the condom wasn't available, it wasn't provided by their partner right, by their male partner. And so even though this might seem un problematic because the idea is that as long as everybody's using the method assigned to them, it should be fine, it'll work out. Right. The reality is it's not all fine, Because it's not just about pregnancy. It's also about protecting themselves from disease. And this set up fundamentally undermines women's ability to protect themselves from disease. And frankly it undermines their right to do so. So it's not okay that it's organized this way and we do need to do something about it.

[00:27:30] Anna: Yeah, absolutely. And you, you also talk about how these problems can go a long way in helping us understand the challenges around managing STD contraction in the U S you say in the book, but presumably the world. So, that's at an individual level, but what about At the societal level?

[00:27:48] Krystale: At the societal level I think we see these skyrocketing numbers right around STI, even as we've had some more success helping reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy, for folks that don't want to get pregnant. We, we do see that we're having a great deal of trouble trying to reduce the spread of sexually transmitted infections. And I think our social approach to birth control is fundamentally a part of that problem, right? If we're teaching people that the key thing to do is prevent pregnancy and that what women have to worry about is using prescription birth control to prevent pregnancy. Of course it's going to lead or shape this outcome, right?

Where people are not having as much success using condoms. And we're not sending the message that they should be using condoms. Right? Our messaging around condom use, specifically as it relates to pregnancy prevention, right, is that condoms are less effective, right, condoms are less effective than prescription forms of birth control. And I had some women talk about how they don't even think condoms work. And this is all part of this broader inaccurate, I need to say messaging. Condoms are quite effective when they are used consistently and correctly. If a person is not using a condom or they don't use it for the whole time that they're having sex, of course it's not going to be effective.

Right. But if people are using it consistently and correctly, it is very technically effective. And so we have this messaging that says that the most important thing to do is to prevent pregnancy. And that the best way to do that is by using prescription forms of birth control. Of course, when you have all of these people who are having sex, and that is the message that they're receiving, it deemphasizes condom use. And that is of course, going to shape people's ability to protect themselves from sexually transmitted infections and lead to continued increase in STI is year after year after year.

[00:29:47] Anna: Um, and even though we have this myth that condoms aren't as effective when they're not used correctly, we say that it's women's fault when they aren't taking the pill at every time of everyday. But obviously, you know, the same can be applied there. That's going to be less effective if it's not used correctly. So it's, it's the same, but yet only one of these methods, we blame the tool instead of the person. Interesting.

[00:30:14] Krystale: It's very interesting. Right? It's a very interesting thing. And I think in only one of these methods, do we endorse the message that it's just hard or it's just unsatisfying, right? Like condoms, people just don't like them and they're just, they're just not as, fun to use. Right. They end up making sex feel less pleasurable for people. And when it comes to prescription birth control, as I talk about in the book, and as we've been talking about, it's not fun for lots of people to use either. Right. But they still do it and we don't let them off the hook, quote, unquote, for not using it given those challenges, right, we don't say, well, prescription birth control can give people side effects and that is hard. And they might have side effects every day for months that they're using it. And so let's cut them some slack and say, hey, this is hard to do, and maybe they don't want to do it and we should come up with something else. Right. Instead we say, you should get on prescription birth control. And if you have hassles with use, talk to your doctor until you find one that works right, we have a very different set of messages. Uh, and I think it's absolutely related to gender inequality and not just related to the effectiveness of the technology.

[00:31:31] Anna: Absolutely. Okay. I want to get into side-effects, but I want to ask one more question or talk about one more thing relating to condoms, because I want to talk about stealthing for a minute, and I don't think you use that word in the book, but you do mention stories of men removing their condoms without their partner's consent, presumably, you know, it's uncomfortable, not as pleasurable. Exactly everything as you say. And I feel like this is one of those under-discussed issues we're going to start talking about it more and more in the coming years, or at least I hope. I know California just passed a law at the end of last year that outlaws nonconsensual condom removal, making it the first us state to do so.

So can you just walk us through this issue? You know, is it considered sexual assault? How common is it? And if it happens to us, is there anything that we can do about it if we don't live in California or a country where it's currently illegal?

[00:32:26] Krystale: So to be completely unequivocal, right. I believe that nonconsensual condom removal is sexual assault. Right. And so that's part of the reason why from my approach, I don't talk about it as quote unquote stealthing, because stealthing focused on what this person is doing right there they're taking it off without somebody's knowledge. Right. And I think that it undermines the fundamental violation of the person's right. This is sexual assault, right? It is taking the condom off without somebody's consent when they had agreed to have sex under a particular set of conditions.

And so in my study, there were numerous occasions where women discussed men taking off the condom without their knowledge. There's one woman that I talk about whose partner regularly took the condom off during sex, without her knowledge and consent and would I see no problem with that until she talked about being mad at him. Right. But even in her mind, she didn't see it as a form of sexual violence. And I think that's what you oftentimes see, which is the import of these laws, right? For people to understand and to have a language for this experience, right. It wasn't just partners being annoying. It wasn't just partners being jerks, which is the way that some of them thought about it, right. It can be understood as a form of sexual assault.

And in my opinion, it can be understood and should be understood as a form of sexual assault. And in terms of what we can do as a society and moving forward, even when we have places where it's not against the law is to recognize that laws only do so much. Right. And that laws are not the be all end, all. There are lots of things that are not against the law when they should be right. They fundamentally violate people's rights and they should be against the law, but they're not right. And especially when you talk about the story of woman. Historically we know there are lots of things that have been agregious violations of women's rights that have not been against the law.

And on the other hand have been codified into law when they are in fact violations of their rights. Right. And so I think for me, the key is to say, we need to be changing the discourse, right? So that even if it's not against the law, that has nothing to do with whether or not it is a violation of somebody's human rights, we need to recognize that it's a violation of their human rights and we need to demand better.

And eventually we have to hope that it's going to be, put into law, right? And that people's rights are going to be protected by law. But until that happens, we need to keep fighting to have these kinds of egregious violations recognized and to make clearer to everybody that it's not okay. But most importantly, to help people who've had that experience come up with a way to understand it and to have the language to discuss what's happened to them so that they don't have this experience of having to deal with in isolation or feeling some sense of shame, right? Because they don't have a language to say that your partner violated your right. Especially when we talk about stealthing, right. This is the thing where the person can have this experience, that's like, this feels egregious to me, but then if we just use this language of stealthing that's kind of makes it about a game in some ways, or just about the act that the person was doing, right. They were still it's stealth removal versus no, if you're feeling incredibly violated, we understand that because it wasn't just a person playing tricks during sex. Right. This is fundamentally somebody who violated your rights and violated your body. and it's not okay. Even if people don't necessarily recognise that.

[00:35:55] Anna: Oh, excellent points. Yeah. Okay. So no more stealthing. We're all dropping that from our vocabulary as of today. And I mean, language is, is so important as, as we'll get into cause that's one thing that you talk about in your book, you know, we can really use language here, so we'll get some tips from you in a bit, but I think this is definitely one that we should all take away.

So to go back now to the side effects, because this is an area that I was definitely wanting to spend a minute on. But to start, you know, can you tell us about some side effects that women might have, or can have when they're on hormonal birth control options?

[00:36:33] Krystale: There are a range of side effects that people can experience. And some people don't experience any side effects. Right? Many people do experience side effects. The kinds of side effects that people can have range from weight gain, emotional volatility, some of the most common ones are spotting. Right? Regardless of the kind of methods that they're using, they might experience a little bit of bleeding in between periods. The other side effects that we've been talking about in the study included headaches. Some of them discussed feeling like their birth control was lowering their libido or making them not want to have sex.

There are just a number of negative side effects that people could experience. And also to be fair, there are some positive side effects, right? Some people talk about having lighter periods. Uh, they talk about having less frequent periods and sometimes we will get on birth control methods for that reason. They want to have periods less frequently. And so there were a number of both positive and negative side effects that people could experience, but the negative side effects ended up making it very, very hard for people to continue to use birth control. And dissatisfaction was a key part of people's experience and a key reason why they might stop or switch birth control methods, even when they wanted to prevent pregnancy.

[00:37:46] Anna: You even mentioned one woman whose nausea from it was so bad that she would just take it at night so she could sleep through it. That was what she saw as her option.

[00:37:55] Krystale: Right. That was her option. She just going to take it at night and this goes back to the messages that we send, right. We don't say your birth control pill is giving you so much nausea, it's so awful that you're taking it at night. Well, people just don't like birth control. Right? We instead say, let's give you ways to manage that experience so that we can make sure that you stay on your birth control method.

Uh, and across the board, women talked about trying their best, right? They tried their best, right? If they had a method that was giving them side effects and making it difficult for them, it wasn't often an experience where they just said, that's it they're stopping. Right. They oftentimes try to find something else, until they either did find something that worked for them, or they decided to stop altogether because it just, they couldn't find something that did a better job.

[00:38:42] Anna: Yeah. And the other part of side effects that I do want to talk about are blood clots. And cause I know that they're rare, but I just feel like this is one of those things that we just accept the fact that some women are going to die and we make ourselves feel better by talking about the rarity. And it is rare, but it still happens. And again, I just feel like we brush it off like it's no big deal. It's just a woman's burden to accept that risk to her life. And often, you know, for the sake of her partner's physical pleasure. That kind of trade-off, to go back to illogical, just blows my mind. I mean, I had a friend who was hospitalized last year in a very serious state because she had a blood clot from her hormonal pills. One that could have killed her and it was terrifying. And she told me that all the female nurses on the heart floor that she was on in the hospital said they use IUD because they've seen so many women come to that floor who have had issues with other methods. So yeah, not really a question, more of a statement of indignation of those two il logical facts.

[00:39:57] Krystale: And I think really a jumping off point for a discussion, because I do think that the key is to think about the conditions under which people are using birth control and whether or not it's liberating, like we were talking about at the beginning. And I think in this case, dismissing women's concerns about blood clots simply because they're rare, is not a liberatory approach to birth control use, right, it is not the way to make people feel empowered around their birth control decisions to dismiss the concerns that they have about blood clots, or to shame them for not wanting to use a birth control method that scares them. Right. Because I think the reality is that even as a person may not want to use a particular form of birth control because of concerns about blood clots, it doesn't mean they don't want to prevent pregnancy. Right. And so what ends up happening is you could have somebody saying, you know, I don't want to use the pill, because I'm worried about blood clots and we meet that by saying, well, blood clots are rare, don't worry about it.

Right. And so I think instead, what we need to be saying is, okay, this person is coming in. They've expressed concerns about blood clots. We need to give them the best information that we can so they understand the context of experience with the blood clots. And if they decide not to use the pill, then we need to figure out is there anything else we can do to support them.

In my research, helping them and holding their partners accountable for using condoms could go a long way, right? Toward, toward not only alleviating their concerns about using a form of birth control that could lead to blood clots, but toward helping them feel empowered about their ability to prevent pregnancy.

And so I think there are, as I talked about it being a jumping off point, right? Because I think there are so many different things that we can do with that information. But the key for me is making sure that we're centering the person's needs, right? Even if they're afraid of a birth control method like the pill, it doesn't mean that they don't have needs. They still have needs. And we need to try and make sure that we're meeting those needs in whatever way we can and pushing them to use a birth control method by dismissing their concerns is just not the way to go.

[00:42:05] Anna: Yeah, that's really helpful. And I think that's what I have the most problem with is it just feels like a bit of gaslighting to just say, you know, it's rare, but, it is a tricky one.

[00:42:16] Book excerpt: “Women’s experiences with contraception and pregnancy are complex, intersectional, and embedded within larger gendered structures that can erode reproductive autonomy on multiple dimensions. Ignoring women’s social context while championing highly effective birth control as the solution to unintended pregnancy prevents understanding of the real social and structural challenges that prevent women from contracepting to begin with. Elucidating their experiences demonstrated the highly gendered, classed, and racialised subjectivity deployed in automatically assuming that their decisions were misguided, careless, or wrong.”

[00:42:48] Anna: So for all of this, do you think getting more options for men would be helpful? You know, it just seems like there are more options for women every few years, but nothing new for men ever comes out. Even though I recently learned that there has been a male birth control pill, some iteration of a male birth control pill that's been researched and trialed for almost as long as the female pill has existed. So do you think more options for men would help at all?

[00:43:14] Krystale: Improving technology without changing our ideas about gender, just isn't going to solve the problem. Right. And in my opinion, I think we oftentimes fall back on these technological explanations. Right. And we'll say, well, it's because there's not methods available for them. And that's why this is happening. Right. And so I think that we overemphasize the power of technology and underemphasize, the centrality of gendered ideas in solving some of these challenges.

Obviously I think we should have more methods, right? I want to be clear on that. We absolutely should have more methods for them, but I think it has to occur alongside changes to our thinking, right? Because we can invent all the methods that we want and there will be some portion of men that will use them, but we're not going to see the dramatic changes that we're hoping for unless we also change our ideas around gender and say it is also their responsibility to try and prevent pregnancy.

There's some research showing that for some men, the idea that hormonal birth control, it might be available for them, it's marketed as making it less likely that they need to use condoms. Right? So it's kind of like, look, hormonal birth control is going to be available or prevent pregnancy. That means that you don't have to wear condoms. Right? So the technology is there for us to use and to try and create the lives that we want to create. But the ideas always go hand in hand with those technologies.

And if we don't have the right ideas, then we're not going to have the right outcomes. And so I love the work being done to try and create these methods for men and people who can get others pregnant. But I think the key is that we have to change our messaging. And while we can't just invent a method overnight and we can't change our messaging overnight, we have more control over changing that messaging, right? Doing the work to try and get people to think differently. We have a lot of control over that even as we have to continue to wait for scientific advances to make the birth control actually available to them.

[00:45:24] Anna: Excellent point, we'll get ahead of the scientific advancement with our language and, um, and human nature. We'll try to that conversation first so by the time the methods come along, we're ready for them.

[00:45:37] Krystale: Right, exactly.

[00:45:39] Overdub: “And now for: “men are losers too”... in gender inequality of course. These are not "women's" issues, these are everyone's issues, because as long as women are held back from their full potential, so are we all.”

[00:45:54] Anna: While we're on topic of men, there is a recurring segment of this podcast that looks at all the ways issues impact men, and what they stand to gain in a more equal world. So could you tell us from your perspective, what do men stand to gain by un-gendering our contraceptives and changing the discourse around these conversations?

[00:46:16] Krystale: Men have the ability to ensure that they're behaving in just ways. And I think that is the key, right? So from my perspective, I don't want to just make it about the improvement to men being that they benefit in some way, I will talk about the ways that I think they can benefit for sure. But I think the key has to be this needs to change, not just because it will benefit men, right. Especially on The Story of Woman podcast. Right. Not just because it has benefits to men, but most importantly, because it needs to be just, and that is the key. So I think the first thing is ensuring that they're behaving in just ways.

Right? So when changing this men can know that they're behaving in righteous and just ways, and that they're not violating somebody else's bodily autonomy. And I think that that is key. And I think that many of them could get on board with wanting to do that. Right. So I think that is the first thing, uh, right. We can hope so. I think that is the first thing.

But beyond that, right? There are a number of ways that changing our approach would be helpful for men because I think the way that we do it is harmful to them, even in ways that might not be understood. And so for one, and I'm thinking specifically about how we don't have access to hormonal birth control for men at this point. Right. And so the change here, would it be changing our gendered understanding and gender behaviors around birth control. And so it could take some of the pressure off of men to always be the ones providing condoms, for example. If we assume that any partner could provide a condom, then women would also, could also be bringing condoms to the encounter and it could then take some of that pressure off of men to always be the one doing that work, you know, making sure they have it available ahead of time.

I think it could also, improve men's bodily autonomy, because if the notion is that the condom is a man's method, then a woman could say that she's on a hormonal birth control method, and then there might be this expectation that he doesn't have to use a condom, because hormonal birth control use is on the table when he in fact wants to make sure that a condom is used.

Right. And so I think we could also do more to center men's bodily autonomy, and their right to use, condoms themselves. So I talk about in the book, how important it is to ensure that women have the right to protect themselves from disease. But the reality is that men also have the right to use condoms, right?

And they have the right to have their partners respect their desires to use condoms when they want to use them. And I think if we can change the messaging around his and hers and instead make it a conversation about respecting the bodily autonomy of everybody involved in the sexual act, then I think that it could go a long way toward protecting men's bodily autonomy as well. Because they have a right to protect themselves from disease as much as their partners do.

And so those are some of the key ways that I think just changing our messaging around it could make a difference, but my last thing would just be, we desperately need to give men and people who can get others pregnant more support around contraceptive use. Right? I talk about this in the book that women engage with their providers much more, right? There's much more support around contraception for women. And I think if we can change this understanding of birth control, then we can understand that men, they need more support, right? It's not, okay for them to only have access to condoms, to not have much information whatsoever about how to negotiate condom use with their partners. They're less likely to have these conversations with providers. And I think that's a key part of trying to change this for the better. If we stop gendering this, then we can realize that we are really doing a disservice to men and how we approach this in the healthcare system. And we might be able to start making some changes there.

[00:50:03] Anna: Hmm. Great. So men, women, and you also talk about how the gendered approaches to birth control also negatively impact trans intersex and gender nonconforming people in overlooked ways. Could you just talk to that point?

[00:50:18] Krystale: This is such a key part of what we need to do to make changes in the future. Right? And so when we talk about his and her birth control, when you go to the CDC website and get information on birth control methods, right and this is changing, which is a good thing, but there's hardly any information that is gender neutral. It is incredibly hard to find information that's gender neutral. And so this idea is that it is cis-gender women who are trying to prevent pregnancy and the cis-gender men who are responsible for wearing condoms and it completely obscures the needs of trans intersex and gender nonconforming people.

So the way that we talk about birth control methods, eliminates them, right. It literally invisibilizes as their experiences. And because information is so important and because feeling supported is so important if there's not even the information for them, right, if they don't even see their experiences, at least reflected in the way that we discuss these methods, we can imagine how it can make them feel alienated and make it less likely that trans, intersex and gender nonconforming people would want to go to a clinic to talk to somebody about their birth control method.

And so I think in addition to making their experiences invisible, it ends up blocking them from accessing a form of healthcare that is vital for everybody who's trying to prevent pregnancy because in addition to the general concerns they might have about being discriminated against, it can make them feel like they don't have a place there.

Right? If you don't even see yourself represented in the discourse and the language, then you of course are not going to say, I need to go and talk to somebody about this because the assumption might be, they don't even know what to, how to help me. Right. And they don't even know about my needs. And so there are a number of really negative ways that this ends up shaping their experiences. But I think that that can be remedied, but we first have to recognise its a problem.

[00:52:14] Anna: Back to language again.

[00:52:16] Krystale: Right. Right. So important here.

[00:52:18] Anna: You also write about the gendered expectations of behavior having a particularly important consequence for the reproductive autonomy of Black women and other marginalized women. So what are some ways that this becomes an issue of race and gender?

[00:52:35] Krystale: I'm so happy you asked this question because this is fundamentally about the ways that race and gender and class really intersect. And so the larger we're going to be getting to language here again, right. But it's about the messaging, right? The larger messaging that so many of us are familiar with says that women need to be responsible for preventing pregnancy using prescription birth control methods.

But what about women who don't want to do that, or who wants to take a different approach. And so when you start wrapping up all of this into this unintended pregnancy framework, which is the typical approach, this is how we end up engaging with this information, right? It's about preventing unintended pregnancies. We talk about the statistic that almost half of pregnancies in the United States are unintended. And so what is the solution there? The solution is to get women to use prescription birth control methods and Black women and low income women. And, Latinx women, their experiences are oftentimes cited when it comes to unintended pregnancy, right?

And there's this notion that they especially need to be on prescription birth control, so that they can make sure they prevent pregnancy. But what I find in my book is that they face unique responses to gender inequality that don't entail them just saying, okay, they're going to use prescription birth control.

So instead the Black and low-income were more likely to expect their partners to use condoms. Right. And what that meant is that they saw prescription birth control use, and condom use as what we call a dual method strategy, or they felt like they should be able to use both of those together, or they felt like they just wanted condoms to be their go-to strategy.

And they didn't necessarily think that they needed to use prescription birth control if they were going to be using condoms regularly. And so of course they couldn't always get their partners to use condoms, like they want it to, and that could lead to not using anything. And so when we talk about the intersections of race, gender, and class, right, we might look at that data and say, Hey, look at this Black women were more likely to not use anything with their partners.

What can we do to get them to use prescription birth control versus recognizing this is a story about gender inequity. They wanted their partners to use condoms. Their partners didn't use condoms like they wanted them to. And so they didn't use anything. This is not about trying to get Black women and marginalized women to be quote unquote, better birth control users when it comes to prescription birth control.

This is a story about remedying, gender inequality in their relationships and in our society more generally, right? Cause it's just a reflection of broader social inequality, right? So we need to remedy gender inequality in the relationships so that we can help them meet their reproductive and sexual health needs.

And so when we think about racial gender and class inequality and the way it plays out, it means that the discourse in public health is about trying to get specific groups to use prescription birth control better, rather than recognizing there are structural issues like gender inequality that gets baked into their relationships, that makes it harder for them to use the birth control methods that they want to use. So let's fix those structural issues so we can better support them instead of stigmatizing individual women and saying that it's their fault, that they are not using birth control like they'd like to using it.

[00:55:57] Anna: Classic blame the woman. And speaking of structural issues, there is a very harmful narrative that exists that says poverty is a consequence of irresponsible people to put it nicely, having unintended pregnancies. And you really break this wide open by asking some very important questions that do not get asked, let alone answered.

So can you walk us through that narrative? Like, Why is that inaccurate and problematic? And what's a better way of thinking about poverty and unintended pregnancy.

[00:56:32] Krystale: Absolutely. So as you're mentioning, this is a longstanding narrative, right, this idea that women are poor because they are not using birth control. And the reality is that people are poor because structures in our society prevent them from obtaining upward mobility, right? It is easy to come up with these individual explanations that fault them for poverty, when the reality is that our society has so many structures in place that make it difficult for them to be able to achieve a living wage, right. Let alone to be able to escape poverty. And so when it comes to birth control use, this is just one more of those things that ends up getting thrown into the mix as something that can help explain poor women's circumstances. People are not poor, because they're not using birth control. I think the real message that we need to be advancing instead is what can we do to better support women in raising and having the children they want to have, not having the children that they don't want to have, and raising the children that they do have.

Right. And that is a reproductive justice framework that ends up getting into these larger structures of oppression and inequality that make it impossible for people live the lives that they deserve to live, and to have their rights in a whole host of areas respected. And so when it comes to thinking about this narrative, the first thing to recognize is that it's wrong.

Right? The second thing to recognize is that it scapegoats people. And the third thing to recognize is that we can take a different approach. But that different. Involves recognizing that these are social and structural issues that we need to solve. And that is about getting into these bigger things that it's not about individual women's behaviour.

[00:58:20] Anna: Absolutely, I mean, I liked, you said we need to stop asking how can we get people to comply, and instead think about what might be happening for them not to quote unquote comply in the first place. It's a great way to reframe that question and exactly as you say, like there's this rhetoric that people are having unintended pregnancies as a result of poverty, instead of poverty being the reason people labeled their pregnancies as undesired in the first place. So you really explain that very well in the book.

[00:58:53] Krystale: Absolutely. And I'm so glad that you elucidated that, right? Because I do think that it's incredibly important to think about the ways that some people have access to labels that others don't, right. Who's more likely to label a pregnancy intended ? If you have the things in place to be able to carry a pregnancy to term and feel like you can give your child everything that you'd like to, it could make sense for you to say that pregnancy is intended.

Versus if you don't have those things, you might label it unintended. And the reality is that person might not ever be able to label a pregnancy intended because they may not ever have the resources that they need to say they intend to get pregnant at that time. time

[00:59:32] Anna: One more question on the context and it's kind of a big one that we could do a whole other episode on. So I just want to like touch on this point that you made in the book was that the management of women's fertility has often been advanced as a tool for solving a variety of social problems. So again, a big question to throw in at the end, but can you kind of give us an overview of some ways that this has happened historically and continues to.

[01:00:03] Krystale: Absolutely. And I think what you hit it on the head again, right, the management of women's fertility has absolutely been used as a way to help at least try and say that we can explain social problems if not solve social problems. And so one of the key things that this makes me think about is the ways that we framed out of wedlock births.

Right? And so when we think about historically there was this understanding and I think it still holds today, that the best family structure is a family structure with two married parents. And the key is parents, right? So don't have children until you get married. And so, in the eighties and you still see some of this rhetoric today, there was this understanding that poverty, was a consequence of people having out of wedlock births. Right? And so the way to solve poverty was to get people to understand that they need to be married before they have children. And as we've been talking about this whole episode, Right. Who do you, they put the focus on, right? We put the focus on women.

So the idea is that women needed to be more selective in who they decided to have sex with. That they needed to only have sex with people if they were serious about them and wanted to be married to them. And there was also this understanding that they should do everything they could to get married first and then have children. And we see that narrative continues today. But it tends to be less tied to this understanding that the reason why people are impoverished is because they're having children out of wedlock. But historically that was a key argument. And we still see that playing out in some ways today. Right. Which is why there is this emphasis on getting low-income and marginalized women to use birth control to prevent pregnancy. Because even though we're not saying it's about out of wedlock births, we're still saying it's about pregnancy, right? People are impoverished because they're having babies when they shouldn't. And so there's this longstanding effort to frame it in that way.

Instead of recognizing, like we said, there are challenges, there are so many challenges that I won't even get into, we can't even get into, we don't even have time for, right. But we make this about the individual woman and her fertility versus recognizing that it's a larger social problem.

And that regulating women's fertility is not going to solve that. I think one more thing that I'll just throw out there is that we might also see this kind of argument being made about mental health and the mental health of parents. And so this notion is that unintended pregnancies could have negative consequences for the mental health of parents.

Right. But instead of recognizing there are lots of things that could be affecting that relationship, we make it about management or fertility, right? Let's have you reduce the chance that you're going to have an unintended pregnancy versus let's focus on the reasons why you might label a pregnancy unintended and how that could then affect your mental health.

Right? So if you are impoverished, that is going to affect mental health. And that is not about having a pregnancy that's unintended, that's not about using birth control. That is about your structural context that makes it hard for people to live their lives without a great deal of stress.

Right? And so even as we consistently return to try and to get people to use birth control in particular ways to prevent pregnancy, the key thing to think about is that we always try and blame women for structural problems and social problems. And the solution is not in their behaviors. The solution is in our social approach to a whole host of aspects of their lives when it comes to income, employment, childcare, right? Those are the areas to focus on. Not trying to get women to not have babies by using whatever form of birth control we think is best for them to use at that point.

[01:03:41] Anna: Love it. I think we can just go ahead and apply that way of thinking to basically everything else. Let's not focus on fixing the woman. Let's look at the system.

[01:03:50] Krystale: Right? Absolutely. Absolutely. We'll get a lot further doing that.

[01:03:55] Anna: Yes, yes. Not fixing the women, not fixing the men, well maybe fixing the men in maybe in some instances, but overall we're talking about the system.

So moving forward, what does an empowered experience using the pill or another contraceptive for a woman actually look like?

[01:04:15] Krystale: It means that people have access to the information that they need to make the choices that they want to make. It means that they can use those methods or not use those methods without feeling pressured or coerced. It means that they feel like they can access those methods when and wherever they need to.

And it means that they feel supported in ultimately being able to make the decisions about their bodies that feel right to them. And I think if we meet those expectations, then we can help ensure that people feel empowered to use birth control. But if we don't, I think that's what you're going to end up, not fulfilling the promise of the pill and other forms of prescription birth control.

[01:04:56] Anna: Hmm. So what do you think it's going to take then to change the landscape to get us to this kind of empowered experience, you know, what does an equitable reproductive society look like? And I don't know how you want to answer that. I'm curious if there already social policies, but also just generally speaking, what do you think it's going to take to change the landscape?

[01:05:19] Krystale: One of the key things is to change sexual education, right? So when you talk about what are the policies, right? So getting above kind of thinking about individual people, right? Our sex ed policies need to change, sexual education in the United States is awful. Largely across the board.

And one of the things that we can do with sexual education is not just make sure that people get comprehensive sex education and have access to information about all of the birth control methods that are available to them. But also that we have conversations about what gender power in relationships looks like so that people have knowledge about what coercion is. Right. What does it look like to not respect your partner's wishes? What does it look like to make them feel pressured, to use or not use a particular form of birth control, when it comes to prescription birth control methods, and how can people negotiate these intimate and sensitive experiences so that they feel like they are having their rights respected by their partners.

And sex education is an ideal place to start, right? Because there's a lot that we can do in that period of time to help people try and create sexually just relationships. Obviously I think we need to change our language, right? That's something that's been the kind of a key theme in our conversation has been changing our language around birth control methods.

And some of that is so easy, right? It's just so easy to stop calling something, a male condom or a female condom, and to get into thinking about other language like internal and external condoms that still make clear the kind of method that we're talking about, but don't rely on this kind of gendered language.

And then lastly, to keep it brief, I think that we could also change our structure around supporting birth control methods financially. Right? So with the affordable care act, not including coverage of a vasectomy, right? So this could be one way that just reinforces pressure on women to get sterilized because it's covered by insurance. And even if they might want to consider a vasectomy, they might be less likely to do so because lack of coverage. And so I think these are some of the things that we can do that would go a long way toward improving the uneven system that we have right now that just creates a great deal of strife in people's lives.

[01:07:40] Anna: All right. So internal and external condoms, no more stealthing. You know, obviously we're all going to be changing our language overall surrounding this, but is there any other words or anything else we can take away with language today to help start shifting the conversation?

[01:07:58] Krystale: I would add reproductive justice. Right. I think that's a term that many people may not be aware of, even though they might be getting a bit more knowledge about it recently, because it's been in the news much more, but reproductive justice is a kind of framework and movement that really centers the right to have a child, the right not to have a child and the right to parent the children that people have. And I think in terms of trying to think about what a just and equitable reproductive society looks like, I think that we need to center a framework like that that really gets us to think about what justice looks like, right. Not necessarily only what equality looks like.

Not just about what our individual desires might be, but also what is a just society look like and how can we all work together to achieve that? So I would add reproductive justice as one more thing that I would love us walk away from this conversation as a new term that we can add to our vocabulary.

[01:08:55] Anna: Added. If listeners take one thing away from this hour and a bit, what would you want it to be?

[01:09:02] Krystale: I would say that it's that reproductive coercion isn't just an annoyance. It's fundamentally a violation of people's rights and that there's a better way forward. So when somebody is telling you a story about something that's happened to them, and it sounds coercive, right. I want us to all be able to just take a step back and before we say that sounds like your partner was being a jerk or boys will be boys. Right. Which is kind of a typical way. We explain these things, right. I want us to be able to say, you know what, this is fundamentally wrong. I'm sorry that happened to you. And please tell me what I can do to offer support so that we can work together to create a better society. Right? Cause reproductive coercion, it's not a small thing, right? It's not just something that is an unfortunate consequence of our society. It's fundamentally about violating people's rights and we need to center the rights of people so that everybody can live freely and joyfully in our society.

[01:10:02] Anna: Beautiful.

[01:10:04] Overdub: And now for: “Your Story”, the part where you are invited to reflect on this story as it relates to your own life - think about it, write about it, talk about it, and if you wish, share with the community. Whether or not you are listening in real-time, if you send in your thoughts, experiences, questions, and recommendations, they may be included in a future listener-led episode. Check out the link in the show notes, or revisit the Your Story episode, to learn more. Remember, no matter your story, you are not alone in your experience, and there is power in our collective realisation of this.

[01:10:46] Anna: So one other recurring section of this podcast is inviting our listeners to think about all of this as it relates to their own lives and then begin or continue to tell their stories. So, Dr. Krystale, as listeners come away from this hour and a bit with you, are there any questions you want to put forth to them as they consider their own narrative, things they can reflect on for their own experiences or anything else you'd like to ask.

[01:11:15] Krystale: Yes. I love to hear more about what their experiences are with genders compulsory birth control and being pressured to prevent pregnancy using prescription birth control methods, if that's happened to them. I'd also love to hear about what they think we should do to change things, right? So I have my own ideas and we've talked about some of those things today, but I'd love to hear what they'd like to see and what specific support they feel like they need to make things more equitable. I'd love to hear that.

[01:11:47] Overdub: And now for: the “feminism gets a bad wrap because the narrative has been just a bit one-sided" corner.

[01:11:54] Anna: All right. Now for some rapid fire questions to wrap up, these are questions I ask every guest at the end. What does feminism mean to you?

[01:12:05] Krystale: I love this question. So for me, feminism is about locating gender inequality at the intersection of other axes of power and oppression. So I know that that's kind of a lot, right, but it's about fighting to ensure that everybody has the right to live freely. And recognizing that when we thinking about intersectionality, right, being a black, queer woman is going to lead to having a specific set of experiences and a specific set of needs. And in order to make sure that feminism itself is meeting its promise, right. We have to make sure that we're always thinking in terms of how gender intersects with these other axes of inequality.

[01:12:45] Anna: Beautiful answer. What is one of your earliest memories of gender, a time when you realized the world didn't treat girls and boys the same?

[01:12:54] Krystale: I would say that it was probably in elementary school when we had to get into small groups and I realized that the boys would oftentimes want to choose other boys for their groups. But the girls didn't always think that they needed to choose only other girls. And so you would end up with this kind of very clear message that like boys wanted to be together and that girls shouldn't be part of that group. And this is what I'm talking like just literally about in class, right? Not about the friendship groups that form, but in class groups that form and realizing that there was this kind of unifying principle that I hadn't understood right. Is being important for people's group decisions, but it ended up being important for them. And so it was really early. I want to say it's probably fifth grade. And I realized that that's how the world worked. And obviously it was, it was a bit of a bummer. It was, it was a bit of a bummer to recognize that.

[01:13:49] Anna: Yeah. Yeah. And so early, woman to what is the story of you?

[01:13:55] Krystale: The story of woman to me is really a tale of gender expansiveness, right? Where we reflect on multiple experiences and positionalities in relation to the identity and we make space, right. We make space for the history, for the feelings, the different kinds of feelings that people might have about the word and the identity. And most importantly, that we also think about the evolving possibilities, right? For a woman, in the future. What does that look like? What does it mean? As I mentioned throughout this podcast, like how can we work together to create a more just future? So it's about history. It's about the present and it's about the future. All really centering an emphasis on the multiple experiences of womanhood and that the identity of being a woman.

[01:14:47] Anna: Evolving future, I like that.. What are you reading right now?

[01:14:51] Krystale: I am finishing up or starting actually, as I said, it was like, I'm reading quite a few things, right. I'm one of those people that read like a lot of different books at the same time.

[01:15:02] Anna: that.

[01:15:04] Krystale: Something that you learned about me today, as I read a bunch of books at the same time. Um, but I am finally, getting into Children of Blood and Bone. And so that's something that I have been meaning to read for a very long time and I'm getting into it now and really enjoying it.

[01:15:21] Anna: Great. And do you have any, I started out by asking favorites, but I think I'm going to just be asking, recommended reading now, any books that you would recommend for our listeners to read after they're finished with yours?

[01:15:34] Krystale: If they have not read Killing the Black Body by Dorothy Roberts, I would absolutely start there. I think that for the kind of work that I do and for the kind of society that I envision, and I would say people that do the kind of work that I do, it's kind of like, Dorothy Roberts is the place to start.

It's accessible. And I think it really is just a spectacular book. So Killing the Black Body by Dorothy Roberts, I would highly recommend they

[01:16:00] Anna: I second that, Great answer. And, um, who should I make sure to have on the podcast? And it's okay to be aspirational.

[01:16:08] Krystale: I think it would be fantastic for you to have a Brodsky who just has a book that just got released called Sexual Justice. I think that that would be fantastic. And it gets into this conversation about stealthing and

You know, it's like what does just sexual politics look like. Like how do we interrogate these terms that so easily get used in our society, but might be communicating messages that we're not always aware of. So I would say alexandra brodsky would be fantastic.

[01:16:43] Anna: All right next season coming for ya. And, uh, what are you working on now?