[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Overdub: Hello, welcome to The Story of Woman, the podcast exploring what a man-made world looks like when we see it through her eyes. Woman's perspective is missing from our understanding of the world. This podcast is on a mission to change that. I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein Lau and each episode I'll be speaking with an author about the implications of her absence - how we got here, what still needs to be changed, and how telling her story will improve everyone's next chapter.

[00:00:34] Section: Episode level introduction

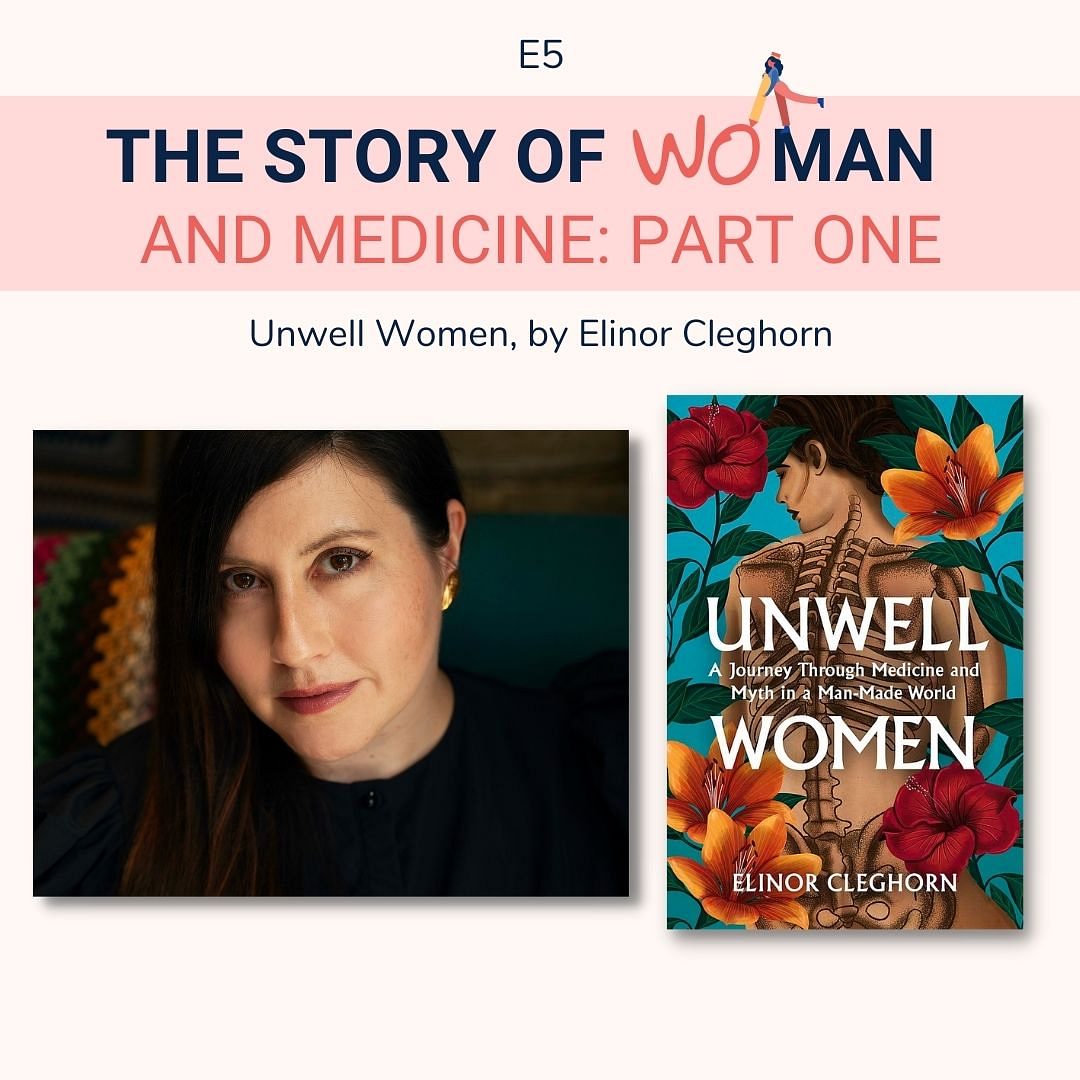

[00:00:35] Anna: Hello friends. Welcome back. I am so happy you are here. My guest today is Elinor Cleghorn, author of Unwell Women, a journey through medicine and myth in a manmade world. And we had such a great conversation and Elinor was so generous with her time that this story is going to be split into two parts, because if I cut the conversation down, what was I going to do? Delete all of the fabulous things Elinor had to say? I don't think so. I would recommend listening to the episodes in order though, as it will just make a bit more sense that way.

When it comes to medicine, women have been called many things, naturally inferior, subspecies, the inverse of males with genitalia turned outside in, witches, beings with menstrual derangement or menstrual insanity, hypochondriacs, hysterical, neurotic, hormonal. The list just goes on. In her book, Unwell Women, Elinor unpacks the roots of this perpetual misunderstanding, mystification and misdiagnosis of women's bodies, illnesses and pain.

The story that she tells begins in ancient Greece, where woman's one worthy possession was the uterus. And so her worth was defined solely by that. And any poor health was blamed on the curiosities of this mystical organ. And this is in fact where the word hysteria originates from. It come from the Greek word for uterus -hystera. But in her book, Elinor takes us through century by century demonstrating how medical progress has not just moved forward in laboratories and textbooks, but how it has always reflected the realities of society and culture and the dynamics of power within them.

Elinor writes that to dismantle this painful legacy in medicine, we must first understand where we are and how we got here. And this is exactly what we will be getting into today. Part one of this conversation includes the loaded medical history of the word, hysterical, why medicine is every bit as cultural as it is scientific and how we can see this legacy still playing out today. Eleanor's story as an unwell woman and how it drove her to write this book. We talk about the role medicine played in the witch trials and the debilitating condition of menstruation, which has been pathologized for centuries and continues to be shrouded in mystery and misunderstanding.

Then stay tuned for part two where we discussed pregnancy, male birth control, the rebranding of hysteria in more recent decades and where we dive into how women have pushed back against all this throughout all of history and still today.

Elinor Cleghorn has a background in feminist culture and history. After receiving her PhD in 2012, Elinor spent three years as a postdoctoral researcher at the Ruskin School University of Oxford. She now works as a writer and researcher. Her writing has been published in several academic journals and she has given talks at the British Film Institute, Tate modern and ICA London. And she has appeared on BBC Radio Four, among many other accomplishments.

Einor's book Unwell Women focuses on medical cultures and the us and UK where Western medicine dominates healthcare. And she notes that her discussions have not extended to the experience of trans, non-binary and gender nonconforming people, not because she believes that gender identity is defined by the biological sex a person is assigned at birth, but because her focus is on womanhood and the historical discriminatory myths about the binary gender differences, so that will be the focus of our conversations as well.

And the quotes will hear read during the interview are taken directly from her book, Unwell Women. All right. I think that about covers it. I hope you enjoy part one of my conversation with Elinor Cleghorn about woman and medicine.

[00:04:50] Section: A word from this episode's supporter

[00:04:52] Overdub: This episode is supported by The Trouble Club. The Trouble Club is a female-led members club that hosts the finest voices on everything from politics to fiction. They just all happen to be women. Trouble is a special society where women and men can learn from different speakers at talks, discussions and intimate dinners. They are here to enliven your mind, to expand your circle of friends, and to build a society of smart and engaged people. A few of the incredible women The Trouble Club have hosted include Laura Kuenssberg, Gloria Steinem, Elif Shafak and Baroness Lady Hale.

Find out more at thetroubleclub.com or from the links in the shownotes

[00:05:36] Section: Episode interview

Hello, Elinor, thank you so much for being here. I'm so excited to chat with you today.

[00:05:42] Elinor: Hello Anna, thank you so much for having me.

[00:05:45] Anna: Yeah, so I doubt there is a woman in the world who hasn't been called crazy or mad or hysterical, but your book really demonstrates the weight of these words and the real life consequences that we will certainly get into. But I mean, this is still so common, right? I feel like it's barely newsworthy when a male politician does it.

[00:06:12] Elinor: So true, because so many of these words to describe women's temperaments, women's personalities and the sort of presumed irrational or deranged, even nature of them are such common parlance on there. When we talk about women, especially when women are in any positions of public participation or in politics or any positions of authority, these words use they're sort of banded around so they diminish women's authority, diminish women's power. And so many of these words do sadly originate from the medical understanding of women's bodies and minds. And they've sort of filtered into our culture as slurs really, as gendered sexist as.

[00:07:02] Anna: I come from a background in nursing and I had no idea how complicit medicine was. And it just is so deeply embedded. And as you say, it does seem to happen even more so when women step out of their designated spheres and into the public life.

But even when I Googled the word "hysterical" in researching for this interview, the example sentence that was provided was " Janet became hysterical and began screaming", not John, but Janet. It runs deep as we will see.

[00:07:34] Elinor: It does run deep as you're completely, right. It's very specifically gendered too. You know, your hysteria is really, even when it is sort of very rarely used as a slur against men it's specifically a gendered slur.

[00:07:49] Anna: So let's start with how this is a historically medical problem. As you point out in your book, we expect medicine to be evidence-based and impartial and to receive fair treatment, no matter our gender, or the color of our skin, but you say that medicine carries the burden of its own troubling history. And that history is every bit of social and cultural as it is scientific. So to start, can you tell us what you mean by that?

[00:08:18] Elinor: Of course. So medicine, since its foundations in Ancient Greece, which is where my book, Unwell Women begins, always reflected, dominant social and cultural ideas about bodies, about people, about what people should do with their bodies, about how they should live. And, in the absence of modern medical technologies, like x-rays, blood tests, other kinds of diagnostic tests, other kinds of imaging, physicians and people who were working with bodies and trying to heal bodies had to really draw on other forms of knowledge about how bodies existed in the world.

So when it came to treating the illnesses and diseases of male and female bodies, a lot of knowledge that was constructed around that was really based on who men and women were in Ancient Greek society. Now, of course, women were seen primarily as reproductive vessels, as creatures whose particular and specific purpose in society was to bear and raise children. And ideas about their bodies being weaker, being less resistant to illness and disease , having weaker humors. These ideas were all based around the fact that a woman was primarily reproductive. So she was always associated very much with her body rather than with her mind, from the very beginning of medical culture. Because women were primarily reproductive in that society, these very foundational medical ideas by physicians like the Hippocratics, from where we get our Hippocratic Oath. Because she was primarily reproductive, their understanding of her illness and diseases really focused on her reproductive capacity.

So the uterus really became the sort of center, the pivotal organ, the primary organ of the female body and all of women's diseases and illnesses were thought in some way to be associated with either reproductive functions or with the uterus itself. So from the very beginning, women get sort of annexed off into this role that's all body, but also all social, it's all about the social duty that women should play. And that is how ideas about women's health really originated very much in line with what was socially expected of women within a patriarchal society, like Ancient Greece. And these ideas, you know, they seem really outlandish to us now, that a woman is all uterus, that she is ruled and governed by her reproductive system. But I feel like the shadows of these ideas are so present now in our contemporary health culture and Ancient Greek ideas are very foundational to thinking as it's evolved over the centuries. So medicine has always reflected dominant social and cultural ideas about people, gender, et cetera, and from ancient Greece, all the way through medicine's history, it's never been separate from society and culture.

Now today, when we hope to have an evidence-based, impartial, objective medical culture, it's still very much embedded with centuries of ideas, of foundational ideas about bodies and health. The residue of these old ideas. There's still very much there. In certain cases, in some understandings of diseases, the foundational knowledge, about how we understand how the body works is imbued with these sexist and misogynistic ideas.

So what I feel like we're grappling now with is the fact that these antiquated sexist ideas are still present in our medical knowledge and in our medical culture. So we needing to sort of separate out the myths, the antiquated ideas, the old stories, the old fallacies, from the kind of objective humanizing knowledge we need to properly care for people and heal them and allow them to live their lives fully and healthily. But we can't separate medicine from the world. We really do have to face up to the fact that medicine is a male dominated practice and art throughout its history has always endorsed and justified dominant ideas about patriarchy because the majority of doctors have always been men up until roughly the late 19th century. And the majority of people who were allowed to practice medicine have been men.

And also the majority of people who've been allowed to write these books, the textbooks, write down the foundational texts that are still with us now, that do constitute that history were all men. And of course they were writing from a position of power in society. They were elite, they were educated, some of the few people who were. And they were very much reflecting the patriarchal status quo. And so, when they are writing about women's bodies, their ideas are spun, according to misogynistic myths that today we need to move away from, but yet we're still grappling with the legacy of.

[00:13:37] Anna: Yeah, I think your book really paints the picture of how we can go from these types of foundational beliefs in Ancient Greece to present day. Because exactly as you say, it can feel so disconnected and like how on earth can teachings from the fifth century BC still be present today, but in your book, you take us through century by century and you see one belief bleed into another belief bleed into another until you arrive to present day.

And it just makes it so clear, where this all originates from. So you did that beautifully, and I want to talk about these myths and then we can go back in time to try to understand how we got here. And your story really exemplifies and is a great example of some of these myths and the current state of medicine. So to start, could you walk us through your experience as an unwell woman and how it led you to write this book?

[00:14:40] Elinor: Yes. So I was diagnosed with an auto-immune disease called lupus in 2010. And I had just had my second baby. And I'd had a very complicated pregnancy, which my son had a heart condition that was extremely rare. And one of the only reasons that this might've happened is that something was happening in my immune system that was damaging my unborn baby's heart.

And so I had various blood tests to see if anything was going on in my immune system. And it turned out that I carried an antibody, an auto-antibody body in fact, that meant that my own immune system was capable of crossing the placental barrier and damaging my baby. So thanks to brilliant consultants, fetal cardiologists, and in fact, the wonders of modern medicine, my baby was born healthy and well with a functioning heart. But nothing was ever really explained about how this strange immune abnormality might affect my own health. And about nine weeks after he was born, my son, I developed heart condition of my own. I was very sick for a few weeks, with a lot of pain in my back and my shoulders, I was very unwell, but every time I thought I should really go and see a doctor, all I could hear in my head was this resounding voice of a man saying, well, of course you're achy, you have a newborn and a toddler. Of course, you're tired. You know, you've just given birth. So all I could hear is this sort of dismissal and doubt and kind of patronizing language.

So I resisted going to the doctor when really I should have gone immediately because my heart, I had a form of heart disease. So when I eventually went I was rushed to hospital and a few days later sent home because I wanted to feed my baby and I was very distressed at being away from my baby. And I was sent home with the note that my anxiety about feeding my baby outweighed the anxiety about my own health.

So it felt like I was being punished again for being this hysterical woman who just wanted to be with her baby. I was still really sick. I got sent back to a hospital and eventually was diagnosed with lupus by a really brilliant rheumatologist. And was treated really well. And now I have specialists care of my diseases is managed. diagnosis was really a vindication for me that I knew that something was wrong in my body and that I had known something was wrong in my body for years, because all throughout my twenties I'd had characteristic symptoms of lupus.

But every time I went to the doctor, I was told it's nothing. Maybe you're still growing at the age of 22. Maybe you drink too much. You must, you know, you could afford to lose some weight. It must be your hormones. It's gout. It's I don't know all these kinds of strange things thrown back at me, but never a complex blood test, never of referral for a diagnostic procedure, never referred to rheumatologists. Always dismissal, always doubt, and always a form of victim blaming, you know, something you have done you're in pain and you are hurting because of your lifestyle or because the pressure you're putting your mind under. And of course, when I was in my twenties, I didn't necessarily understand that this was happening because medicine had this systemic gender problem. I just thought it was me and that I must be fussy and I must be making it up. So to be diagnosed was really a vindication for me because I knew and I was right and I was right to pursue my instincts and to try and get answers even though at the time that was in vain.

So gradually I began to sort of mine medicine's history for answers about my own disease, although I was being treated so well, medicated, cared for now, there were many questions I was asking that just couldn't be answered by my doctors and consultants. I wanted to know why my pregnancy in particular seemed to have triggered this massive flare of the disease.

Oh, it might be hormones. We don't really know. Okay, 90% of suffers of lupus are women. Why is that? Oh, we don't really know it could be hormones. And it's kept coming back to these sort of mystified, you know, vague notions about women's hormonal complexity. There seemed to be a real through line with this, right, being told that my disease was something to do with my erotic woman's and then all those times in my twenties been told, but my pain was all my hormones. You know, there seemed to be this real tendency to fall back on lazy, stereotypical ideas about women's bodies being alien or complex or mystical, and that being a reason why we don't understand enough about them and we don't need to diagnose them properly. I just, the book really evolved from there. That was the germination of the idea for Unwell Women. And it happened quite slowly. I started to write about my disease and kind of creative writing. I started to write about it from my own perspective, and then I wanted to sort of zero back into the history and make my story just one part of that history, rather than having, you know, a memoir that your own history. I wanted my story to be almost like a case study in amongst all these other case studies from the history of medicine So it really evolved from there. So it was deeply personal motivation for writing the book, but also it was my attempt to say, look, this has happened to me, but every woman I have ever spoken to has had some form of this experience. it's been trying to, you know, be treated properly for something in the life cycle, like a menstrual issue or perimenopause symptom, whether it's been related to fertility and pregnancy or to a chronic disease or illness, every woman I've ever met or spoken to you and know has some version of this story.

So it felt really important to acknowledge that. So even though I was drawing on past my experience, it was also my attempt to say, look, I acknowledge that this is happening and has happened to hundreds, thousands, millions of women across the globe.

[00:21:15] Anna: I am so sorry that you know, you had to go through that in order to get the appropriate treatment. And I wish you were an anomaly, but as you say, unfortunately, that's just not the case. How long did it take you to get your diagnosis? Cause I know you said in the book, it takes on average almost five years in the U S to get a diagnosis and three in the UK.

[00:21:39] Elinor: Yeah. So it took from when I went into hospital until my diagnosis was about 10 days. But in actual fact, I began, I think getting the symptoms of lupus when I was about 21, 22. So it was more like sort of seven or eight years of undiagnosed misdiagnosed symptoms. And speaking to my consultants, now they have acknowledged that yes, everything you described is a very classic presentation of lupus.

It tends to emerge in younger women. So, you know, late teens, early twenties. It can be triggered by hormonal events. It can be triggered by all sorts of things. Environmental factors, genetics, so many unanswered questions around it. They said you had a very typical presentation and I also have a genetic abnormality, I have a protein, strange protein that is very indicative of having an autoimmune disease. So this could have been shown with a really simple blood test. So this is what is also so flummoxing and so enraging about it is that there are simple ways to ascertain whether there's something more complicated going on, but it's just that when we don't know where medicine doesn't automatically know the reason for a person's symptoms, they do tend to fall back on lazy assumptions about gender. And it always seems to happen when the illness or disease doesn't immediately present itself.

[00:23:06] Anna: What other conditions do we see today that carry this kind of legacy? So your experience was with lupus and we know that lots of mystery still surrounds the reproductive system and menstruation, menopause, what other kinds of conditions do we see that have this kind of mysterious legacy?

[00:23:27] Elinor: I think anything that associates back to women's reproductive or menstrual cycles and systems does tend to be shrouded in this degree of mystery and mystification. A disease like endometriosis, I always feel is an object lesson in medicine's failing to separate its assumptions about women from its objective kind of knowledge about how bodies work.

I think it's the perfect example because endometriosis is a disease that today can take up to 10, I read the other day, even 12 years to be conclusively diagnosed. And one of the reasons for this is that endometriosis and the multi symptomatic disease, like auto-immunity, it's very unique to the individual, but it does have some certain things in common.

So it might present initially with abdominal, pelvic menstrual pain, with heavy menstrual bleeding, for example, and these kinds of symptoms are gate kept, I feel. They are gate kept by these sort of sexist ideas that, well, on the one hand, if you have menstrual pain, it's just your lot in life as a woman to experience that. It's built into your body, it's what women's bodies do, they hurt. What more do you want? You know, and on the other hand, it's this complete lack of knowledge clear, unambiguous knowledge about how to diagnose a condition like endometriosis conclusively, quickly, so that somebody can be treated and cared for properly. So it's these two things kind of come up against each other in cases like endo. Lack of knowledge, prejudice against women's expressions of their pain, mythologies around what it means when a woman is in pain or when a woman bleeds, they all sort of intersect in endometriosis. And endo was first properly described when it was named in the 1920s. But if you look through the history of medicine, the symptoms are described for centuries, and yet today, still in the 21st century, we're expecting people with endometriosis to struggle to find a conclusive diagnosis for up to 12 years.

You know, this . Is a historically recognized disease. But yet every time it's been studied, we've come back to these associations and assumptions about who women are, what they should do with their bodies, with their lives. In the 1940s when endo was studied fairly widely by American physicians, it was assumed that endo was caused by women deciding to have babies later, because of course, you know, we're just after The Great Depression, there's a lot of financial instability. And at the same time, women are having more opportunities to enter the workforce. So of course they were not necessarily getting married at 18 and having four or 5, 6, 7 children. So the doctor who was describing endometriosis in the forties, a man called Joe Meeks decided the endo was almost a punishment for women putting off childbearing and focusing instead on their lives and career. And he actually advised that young women who had wealthy parents should be given their inheritance when they got to 18, so that they were free to marry and have children because he believed that persistent menstruation was the reason for endo which is completely factually incorrect. But yet these mythologies still state, many women are still told, well, you better hurry up and have a baby or suggested that they might have a baby in order to cure the symptoms. For some people, it can help, but it's not a cure. And it's also not, you know, any doctor's business to impose, impose pregnancy on a, on a person, as a cure for a disease. Pregnancy is not curative. So we can see from a disease like endo, how persistent these mythologies are.

[00:27:31] Anna: Yeah. And that is straight out of ancient Greece. I mean, that is the prescription that was given back in the fourth and fifth centuries BC, as you lay out.

[00:27:44] Book excerpt: “Gender difference is intimately stitched into the fabric of humanness. At every stage in its long history, medicine has absorbed and enforced socially constructed gender divisions. These divisions have traditionally ascribed power and dominance to men. Historically, women have been subordinated in politics, wealth and education. Modern scientific medicine - as it has evolved over the centuries as a profession, an institution and a discipline - has flourished in these exact conditions. Male dominance - and with it the superiority of the male body - was cemented into medicine’s, very foundations, laid down in ancient Greece.”

[00:28:20] Anna: Let's go back. I want to do a little whistle-stop tour through time to try to figure out how we got to this place, where the se conditions we've mentioned lupus, endometriosis, there's more- you talk in your book about fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, which has been re classified as myalgic encephalomyelitis, MS, and the list goes on. So all of these which have these commonalities of majority women suffers, difficult to explain, blaming psychological and emotional, leading to the self fulfilling prophecy, where as you yourself say, we start to question ourselves and not believe our own bodies because objective medicine tells us we're fine.

So you've mentioned that this all stems from ancient Greece and the Hippocratic Oath, which I just found very ironic given that, you know, the Hippocratic Oath is all about vowing to do no harm. And you know, you do point out in your book and I think it is worth noting that you don't think the vast majority of doctors are consciously dismissing women out of hand, but this discrimination consists because of this long shadow.

And then in that way, I kind of see this Hippocratic Oath as a double-edged sword, that we tend to give medicine the benefit of the doubt, knowing that they vowed to do no harm, but at the same time harm can still arise from everything that we've laid out. So starting there. What were some of these theories about why the uterus was so troublesome and what was the cure?

[00:29:57] Elinor: So Hippocrates was a physician in Ancient Greece, but his writings were actually authored by different physicians who studied with him. It's very hard to know whether Hippocrates is actually a one figure or many, but we usually say the Hippocratic physicians, but they wrote treaties on the care and treatment of women's bodies and illnesses.

And of course the uterus was, you know, the lead player, the protagonist in these writings. And the Hippocratic physicians described different courses of symptoms that they believed were caused by the uterus being unsettled in relationship to its procreative or reproductive functions. So in the eyes of the Ancient Greek physicians and the Hippocratic physicians, healthy women was pregnant, was conceiving, was in the process of conceiving a baby, was carrying a baby, was bearing a baby, was raising a baby. This was the ideal health full state from women's body to occupy. And they believe that when a woman was not performing these duties, when her uterus was in want if you like of performing its desirable function, that it would become unsettled, unruly, ill, unwell, that it would start to become untethered from where it should belong in the woman's body and actually start wandering around and creeping up her body in search of the moisture that it should be furnished with by sorry, male seed to use an Ancient Greek way of putting it.

So the uterus, they believed would become dry if it wasn't, you know, involved in making babies. So it would creep up towards the liver searching for moisture, creep up towards the heart. And as it did that would compress those organs and cause a veritable catalog of strange symptoms. And those ranged from physical symptoms, pain, fevers, convulsions, and also to psychological symptoms, hallucinations fits of madness and so on. So the cure, the ideal cure for say a younger woman who had not, was not yet married, but was suffering from afflictions of the uterus. The ideal cure for her would be to be married off immediately and start having babies. And the average age of having babies in Ancient Greece for women was between the ages of 12 and 14, which is extremely shocking until you remember that life expectancy was about 30.

[00:32:43] Anna: Wow.

[00:32:44] Elinor: Yeah. And then for a woman who was say nearing the end of her fertile life, there were other proposed treatments that included things like fumigations, which were either sweet or fetid smells, so burning different materials. And it was believed that the uterus was attracted to certain smells. And that if you kind of had these fumigations going that the uterus will kind of hopefully fall back into its rightful place.

So what's really interesting about all this is that from the get-go from the very beginnings of the Western medical Canon, the uterus is described as having almost a mind of its own. It's described as this entity that has animate impulses that hungers above anything else for intercourse, for conception and for pregnancy, and this idea of attributing to it, the capacity to walk around the body, wander around the body move, and have a capacity to smell things. like it's this sort of, homonculus like there's other, other being that exists in a woman's body that she has very little control over, very little rational control over. So something like the wandering womb, again, it sounds ridiculous. It's really easy to make fun of those daft, old, Greek, white dude's believing a womb could create per round like a creature, but the implications for that kind of mythology, we can see how impactful that idea was over the centuries.

Even when dissection and anatomical studies soundly disproved the idea that a womb could move because it was tethered to sinews and tendons. The very notion that there is something in a women's body that wants above anything else to perform a reproductive function, really set up this idea that a woman is not in control of her body and that she doesn't know about her body, that she's not the authority around her own body and her symptoms and that she hasn't got any ownership around her own body.

That her body is always a matter of somebody else's analysis, somebody else's study and primarily a man. So it's very convenient, you know, that there's social expectations for women to produce children to produce heirs, is wrapped up so intimately with their health. So from the beginning, from the Ancient Greek times, you get this way of policing, what women should do through what is best for their health. And that's what I think is really fascinating. And that's what I think we really do still inherit today. And that we still grapple with.

[00:35:27] Anna: Absolutely. The uterus is still the defining factor for women and it is still the most controversial part of healthcare. And as you've pointed out with endometriosis that there's still direct legacy just from this prescription of marriage and pregnancy. And you know, if women's differentiator, is this very important organ that gives life to all humans, how did they not come to the conclusion that the uterus and being able to create life was not inferior deficient, but superior, you know, you think they might've come to that conclusion instead.

[00:36:04] Elinor: This question, baffles me all the time and it's such an important one, but I really think it comes down to how, sort of distribution of power and the perception of this incredible procreative power that women hold. And it's such an incredible source of power is literally the origin of new life, is literally the future in its making.

And I really believe that in terms of, you know, why women's bodies had to be spun as inferior is because we do contain too much power. We do so, it had to be dulled, it had to be diminished. It had to be controlled and curtailed, and we of course see that happening in violent and brutal ways across our history as well, in terms of the control of women's bodies, especially in a reproductive sense, right? We have this power, we have this agency, we do hold the most mysterious and still very mysterious power to bring new life into the world. And yet too much power is attributed, it has to be curtailed.

And that's what I believe. I mean, it was interesting, I was talking to someone recently about many of the Greek myths that attribute the procreative power to the male God. And it's strange the way that these old mythologies sort of grapple with this inexplicable idea that women really do hold this generative power and men don't. Men hold the parts of control it though. And yeah, that's how I think it's unraveled. And that's why I think that medicine, as a system of power, as an agent of patriarchal power throughout its history, has always insisted on this way of pathologizing women and reducing them to this organ, rather than to their minds, to their rational control. It's always a way of asserting this power over them.

[00:37:59] Anna: That was definitely a common theme throughout the book was that it seems to be about power and control.

[00:38:05] Book excerpt: “The ancient Greeks had blamed all the sickness of the world on Pandora, the mythological first woman, who was too weak to resist opening the forbidden jar of evils that her husband Epimetheus was taking care of. Christianity spun a different story about women and their bodies being responsible for all the sin in the world. The Book of Genesis decreed that Eve, the original woman, imperfect and incomplete from the get-to – and an afterthought spawned from Adam’s rib – ruined everything because of her desirous and disobedient ways.”

[00:38:40] Anna: So then as civilization moves on, from ancient Greece, we move on to the middle ages. We see the rise of Christianity across the Western world. How do we see women's role within medicine and society start to unfold?

[00:38:56] Elinor: So with the rise of Christian theology, of course came a whole new set of myths about gender, myths about who women were and what women did. And of course, with the story of Eve, women's bodies . Become responsible for all the sin in the world. Women's bodies are literally responsible for the unleashing of sin. And it's not just women's bodies, but women's propensity to be tempted, women's propensity to be weak and above all their propensity to be all body over mind. And so with this foundational meth and the rise of Christian theology, it was again, very easy to double down on ideas that women's bodies were not just weak and inferior, but potentially poisonous and corruptible. They have this very corrupting influence because of their weakness. So when we get the foundation of Greek myths about women being physiologically inferior, biologically weaker, you then add to that very potent mix, a new story about how women are essentially sinful.

You know, that just by existing in a female body, you are, you carry that potential for sin, that's really quite the concoction for creating some new, dangerous and disparaging myths around women's bodies. So by the time, Christian theology really becomes reflected into medicine, you know, we have centuries of medical knowledge from the Greeks being translated and transmitted into Latin. And of course, when it was translated and transmitted, it was recast according to these new Christian mythologies that were very misogynistic. And so where a woman's womb might've wandered in ancient Greece in 13th, 14th century, it was now, you know, wandering with a malicious intent. You know menstruation was dangerous, poisonous, could inflict disease. You know, women had to be controlled through religious prayer, only the most virtuous and penitent women were free of the dangers of their bodies. And this sets up a very, very dangerous precedent for women being punished. Purely for the fact of existing in a female body.

And we all know of course, about the witch trials, which plagued Europe from about the 15th century to the 17th century, and although medicine did not create the witch trials, it was certainly a very active player in creating the climate of suspicion and doubt and distrust that hovered around women's bodies, especially in relation to what women's bodies would perceive to be capable of. So it had a major role in that kind of culture. So by the time we see the rise of women being tried, accused and sometimes punished and executed for witchcraft across those periods of time in the middle ages and early modern period, there are often these biological justifications for why women would be consorting with the devil to bring about evil on earth and do his works in the world. And one of those was that women are biologically weaker, that because there's something in their body that hungers for copulation, for intercourse, it means that they were easily susceptible to this sort of influence from the devil.

And again, it sounds so absurd, even as I'm saying it, I'm thinking I'm literally talking about women having sex with devils, but this was so feared. And so believed at this time in history and women were scapegoats for all sorts of other events that were inexplicably in the world, plagues pestilence, disease, poverty, drought, it was much easier to blame women because they were so weak and incorruptible as the Bible taught people, than it was to really grapple with the idea that the world is this big volitional thing that makes events happen. No, we don't have understanding of disease and disease transmission. We don't have understanding then of cycles of poverty, of weather events. So that is how this knowledge happens. That's how these ideas become so embedded and extremely sadly what ended up happening was, you know, mass persecution of women across Europe that ended up with, I believe about 45,000 women being executed for crimes of witchcraft.

[00:43:29] Anna: 80% of whom were over the age of 40 you point out because menopausal symptoms carry their own accusations of witchcraft.

[00:43:38] Elinor: Absolutely. That's completely right. About 80% were over 40, which, you know, I'm 41. So it's kind of, but again, life expectancies were much lower than, so these were women who were at the end of their, approaching the end of their lives. They would definitely pass their fertile lives. And there was great suspicion of course, at that time of women who were no longer socially useful. Right? So coupled with the possible symptoms of menopause or perimenopause, which medically were not understood at all then, would produce some of what you might call the symptoms of witchcraft behavior.

So in the accounts of accused witches, you often hear, you know, the story of a woman who was cantankerous or argumentative or bolshy or independent or loud mouth, all these sorts of things that we now expect women to do to stand up themselves, you know, essentially speaking out of turn, appearing in public, daring to maybe have relationships, to speak their minds. And these could be used as proof that a women was somehow consorting with the devil to inflict ills on people or on the neighborhood or the village or whatever. But what really descended quite quickly in the witch trials was that it soon became a matter for local courts. And it was really exploited the sort of craze if you like for accusing people of witchcraft was often exploited in disputes between people in villages.

So it became a very canny way of getting revenge or blowing up a sort of idea about someone and, and then, following through with a often false accusation. And yeah, the idea of this sort of crone, like the wisdom crone who eats children in fairytales, very much from this era, this image of what would a woman be if she was so deceitful and evil that she consorted with the devil. Again, it's so crazy, but it really, it happened. And it happened because of an evolution of ideas that became embedded about what women's bodies were capable of.

[00:45:45] Anna: Yeah. You wrote that in one of the books, which explained how to identify suspected witches, it said "in order to infect a woman with witchcraft, she must have any one of three specific vices: infidelity, ambition, and lust", which I think, you know, ambition is still something that women have to be cautious when wielding today anyway. And also around this time, there was a book called The Secrets of Women that was published to instruct church men, who of course were the medical practitioners of the time on fertility, conception and . Pregnancy. And I just want to read a short passage from this medical book, which you write that it says:

" Women are monstrous. Their infirmities, lead them to do sinful things for menstruation is the root of all women's evils. When a woman is menstruating, she can poison animals with a glance, infect children in the cradle, dirty the cleanest mirror with her vial reflection and transmit leprosy and cancers to men. It is very important that priests understand such things for evil cannot be avoided unless it is known."

Exactly as you say, you know, this sounds ludicrous to us today, but this book, and others just like, it were used for teaching in universities and in science and philosophy all across Europe, you know, it was disseminated far and wide to the medical practitioners of the time. And today there are people who see menstruation as a reason, women shouldn't hold positions of power. So I'm curious what you think of that. You know, where are we today in terms of accepting and understanding menstrual health and from your perspective, how has this past helped to lead us there?

[00:47:44] Elinor: I think that we are still very much in a sort of mythologized and antiquated space when it comes to understanding menstruation and menstrual health. Menstruation is so shrouded and myths and old fictions and prejudices and strange ideas, even today when I do feel like we're having this moment in our culture, when we're really encouraging the sharing of menstrual experiences, you know, the accepting of menstruation as part of our bodies, as a unique and important part of what our bodies do. And I do feel like that's happening and I'm really hopeful because of that shifting culture, but still everywhere you look, you see the residue of these ridiculous, ludicrous, old ideas that menstruation is somehow this source, maybe not demonic anymore, but as sort of source of derangement in women, like it signifies a derangement of ration and mental functioning.

And in the most crude samples we saw it when the 45th president of the USA talked about why Hillary Clinton shouldn't take office because, you know, she was menopausal And this idea of going back to a women's fluctuating hormones, this mysterious fluctuating hormone cycle, as the way to bar her or exempt her from positions of authority, definitely began in those early theories about menstruation being the source of trouble, in that case of the book, The Secrets of Women as source of profound evil. And there's another piece in that book that suggests that a menstruating woman is very, sexually aggressive and will deliberately try to lure men to have sex with her when she has her period. And that while she does say she would have inserted pieces of iron into her vagina, because she was intent or mortally wounding her partner.

[00:49:34] Anna: Oh, my God.

[00:49:36] Elinor: This is awful. It's a horrible and ridiculous line in that book, but it also plays off two really interesting ideas that a bleeding woman is vengeful, angry, evil, crazy. And also that a bleeding woman is this kind of sexually libidinous, sort of excessive, uncontrollable, untameable creature. And today I feel like these two things are so with us, you know, like the wandering womb in ancient Greece, women's hormones are now seen as almost that independent entity that controls how we think and behave, you know, that we have no agency over. We are all the hormones. And so much of the understanding of menstruation, clear on ambiguous understanding of menstrual health, of menstrual wellbeing, is still clouded by these old assumptions that when we menstruate or throughout our cycles, we are not in control of what's happening to us.

So we've sort of abdicated our rational minds to this bloody hormone or chemical concoction that you know, is kind of controlling us from the inside out. And from something like The Secrets of Women, which was indeed ludicrous and enraging, the idea that women's menstrual cycles do dictate their behavior and habits, but also limit what they can do in life persists throughout the centuries. And when we see it returned to when women are trying to argue and agitate for more professional and political and social opportunity, we see a real trend, and this happened in around the mid to late 19th century, of male doctors or sort of Dr. adjacent figures in society, arguing against the expansion of women's rights because women bleed.

[00:51:21] Anna: Of course. Yeah, That's where we wanted to move on to next, so we have gone through Ancient Greece, the Middle Ages, and then we move to the late 18 hundreds when women start demanding, as you say, equal education and suffrage. So seeing these objectively have nothing to do with medicine, I didn't quite expect them to pop up in this way in your book. So, can you tell us what the medical community had to say about women's participation in these areas?

[00:51:55] Overdub: Ooooo I am sorry... that is where we end part 1... what a tease... tune in to part 2 of this story to hear what elinor has to say about how the medical community felt about women going so far as to demand the right to vote and get an education AND how women responded and began to make their way into the male-dominated medical institution... And because I am sure you are on the edge of your seats, i’ll leave you with a little teaser to show you what you have to look forward too... see you back here soon!

[00:52:28] Elinor: One of my favorite figures in the book as an American physician called Mary Putnam Jacobi, who argued against a Harvard doctor who was really, leading these campaigns to say women would get so menstrually ill if they went to school, that they should be practically barred from getting an education. And she debunked this by doing research with actual women.

[00:52:49] Anna: Woah.

[00:52:50] Overdub: Thanks you for listening. The Story of Woman is a one-woman operation, with voiceovers done by Jenny Sudborough.

If you enjoyed this episode, there are a few small things you can do that make a big difference in helping other people find the podcast and allowing me to continue putting out new episodes! You can subscribe, leave a review, share with a friend, follow us on social, buy me coffee (not literally - this is the name of the platform to raise production funds - but hey, I’d grab a coffee as well), or head to the website and check out the bookstore filled with 100's of books like this one. If you purchase any book through the links on the website, you support this podcast - and local bookstores! Soooo feel free to do all your book shopping there! All of these options are in the show notes.

Anything you can do is appreciated and makes a big difference in elevating woman from the footnotes of history to the main narrative.

💌 Sharing is caring