[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Overdub: Hello, welcome to The Story of Woman, the podcast exploring what a man-made world looks like when we see it through her eyes. Woman's perspective is missing from our understanding of the world. This podcast is on a mission to change that. I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein Lau and each episode I'll be speaking with an author about the implications of her absence - how we got here, what still needs to be changed, and how telling her story will improve everyone's next chapter.

[00:00:34] Section: Episode level introduction

[00:00:35] Anna: Hello friends. Welcome back. And thank you for being here today. We are talking about the latest organ that has been blamed for women's inferior position in society: the brain. And I say latest because as we will see with the upcoming episode with Elinor Cleghorn, who wrote Unwell Women, this is not the first organ to be blamed. Just the most recent.

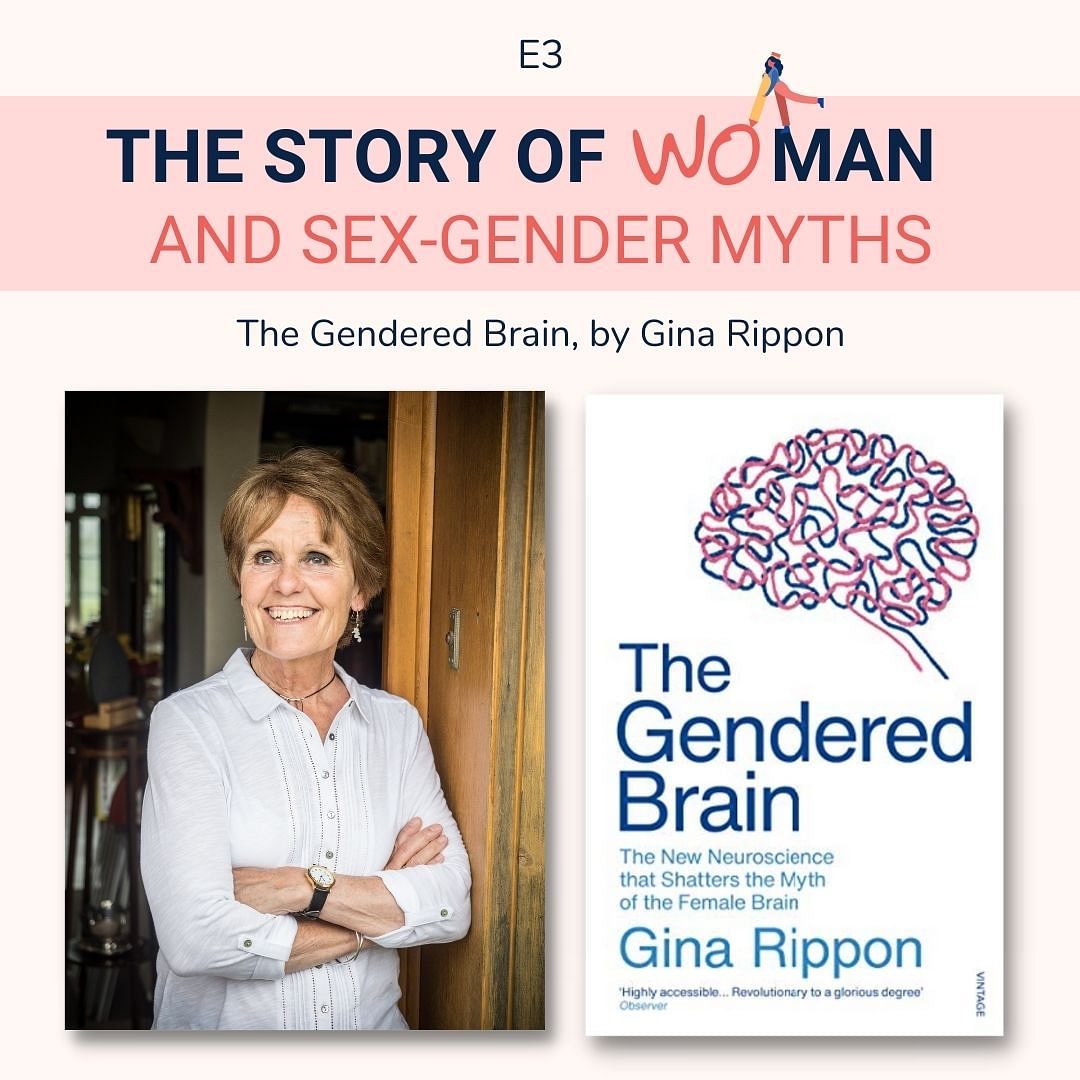

My guest today is Professor Gina Rippon, and we will be discussing her book, The Gendered Brain. Every single day, since the day we are born, we face deeply ingrained beliefs that our sex determines our skills and our preferences, from toys and colors to career choices and salaries. So girls prefer Barbie over Legos, and women can read emotions but they can't read maps, and only old, white, men can be scientists.

Obviously I'm being a bit facetious, but these stereotypes and beliefs have so much history and are so pervasive that they continue to inform and shape our world. I mean, as Gina points out in her book, even Charles Darwin, the author of one of the most important scientific theories, had these views about half the population he was studying. He said, quote, "The chief distinction in the intellectual powers of the two sexes is shown by man attaining to a higher eminence in whatever he takes up than women can attain, whether requiring deep thought, reason or imagination or merely the use of the senses and hands".

And Charles not only thought women were inferior and less evolved than men, but also that any attempt to expose women to education or independence could damage the process of evolution. So it's no wonder these myths continue to linger when such an influential person held these beliefs not very long ago.

But using the latest neuroscience and hundreds, if not thousands, of research papers to back it up, professor Gina Rippon unpacks the stereotypes that bombard us from our earliest moments and shows us how these messages, mould our ideas of ourselves, about each other and even shape our brains accordingly.

Professor Gina Rippon is an international expert on brain imaging techniques and Emeritus Professor of Cognitive Neuro Imaging at the Aston Brain Center and Birmingham, England. Her research involves state-of-the-art brain imaging techniques to investigate how the brain interacts with its world, and what happens when this process goes wrong. She currently works in the field of autism spectrum disorders, where she is a part of a team investigating abnormal patterns of brain connectivity.

And she is an outspoken critic of "neuro trash", which is the populist misuse of neuroscience research to misrepresent our understanding of the brain, and most particularly to prop up outdated gender stereotypes. In her book, The Gender Brain, which is called Gender and Our Brains and the US edition, she challenges the idea that there are two sorts of hard-wired brains, male and female, and offers a 21st century model for a better understanding of how brains get to be different.

In our conversation today, we talk about the origins of these myths and what has perpetuated them all these years. We talk about the importance of stereotypes and also the detriment of them. We talk about how early these stereotypes and the gender bombardment begins and the serious implications of the toys and messages children receive from day zero. We talk about self-esteem and self silencing and the lack of women in certain fields of science. And we talk about the future of sex and gender and where we need to go from here in order to get rid of these myths once and for all.

And the underlying theme through it all is not that sex doesn't matter or that there are no differences, but that we need to go beyond the binary because, as Gina puts it, there is no such thing as a typically female behavioral profile or a typically male behavioral profile. Each of us is a mosaic of different skills, aptitudes, and abilities, and attempting to pigeonhole us into two archaically labeled boxes will fail to capture the true essence of human variability.

You will hear Cordelia Fine mentioned a few times, so just so you know who she is, she is a philosopher and psychologist and has written at least four books on the subject. And the quotes you will hear read during the interview are taken directly from Gina's book, The Gendered Brain.

As always feel free to share, to help spread the word that women are in fact, capable of being scientists and reading maps, and that men are capable of having emotions. But for now, please enjoy my conversation about the gendered brain with professor Gina Rippon.

[00:05:47] Section: A word from this episode's supporter

[00:05:49] Anna: This episode is supported by Virginia Mendez, a feminist author, public speaker, and co-founder of the feminist shop. The feminist shop is an ethical brand that covers all basis to fuel your feminism, from free content and resources to over 400 book titles and a large selection of ethically produced apparel and gifts to make statements and start conversations. All while giving back to associations.

Virginia has written two bilingual children's books, one inviting kids to challenge gender stereotypes, and the other one opening the conversation about consent. And she is in the middle of promotions for her first parenting book: Childhood Unlimited- Parenting Beyond the Gender Bias. It's full of tips, information and tools to free our kids from the limits of bias. You can find links to the shop and Virginia's work in the show notes and on the story of woman website.

[00:06:39] Section: Episode interview

[00:06:40] Anna: Hello, Professor Gina Rippon, welcome. Thank you so much for being here.

[00:06:45] Gina: Thank you very much for asking me.

[00:06:47] Anna: It's great to have you. So, it seems pretty unfathomable that we would be sitting here in, 2022, about to have a conversation about if the brain inside a woman's head makes her incapable of leading a country, becoming a scientist or reading a map. Is this really still a thing that people believe?

[00:07:13] Gina: I'm afraid. It very much is still a thing. It's certainly unconsciously a thing. And sometimes consciously, sometimes there's kind of public outbursts about, you know, Google wasting its time educating women to be Google engineers or something. But I think there's clear evidence that, this belief still informs a lot of attitudes towards females or males indeed. And also, attitudes of self-belief as well.

[00:07:40] Anna: Yes, which we will definitely be getting into, well, I hope anybody who does still believe this to be true reads your book because it was fantastic, very thorough and well evidenced as you might expect from a neuroscientist. And, and very funny, you're a very funny neuroscientist, which I guess makes you two things that women supposedly can't be -funny and a scientist. So you yourself are just shattering this myth. So, the subtitle of your book is the new neuroscience that shatters the myth of the female brain. So I want to start there by having you define for us, what do you mean by " the female brain" and what is this overarching myth that persists about it?

[00:08:28] Gina: Well, I mean, that's a good question because in fact, if you start to unpick the terminology, sometimes you can get towards the answer that way. The idea of the female brain really goes back to the end of the 18th, beginning of the 19th century when there was a very strong belief, right at the beginning of research into the role of the brain in human behavior and human society, that there was clear differences between males and females. And these were catched in terms of the female being inferior, because scientists worked backwards from the status quo and indeed women had an inferior position in society. So the aim was to A identify the female brain and B prove that it was inferior because then justified science's "hunt the difference" agenda if you like.

But what the story really is is that whatever it is that made males and females anatomically different, because at that stage, they didn't have access to genotypes, or know about hormones. Whatever it was made, males and females anatomically different, also made their brains different. And those different brains actually had a different portfolio of skills and attitudes and personalities which then gave them a predetermined, predestined place in society. So the female brain, you know, was an anatomical reality to early researchers.

[00:09:49] Anna: All right. And, I guess the myth that exists about it is essentially that that is what gives women their inferior status in society?

[00:09:59] Gina: Yep. Well, I think, I mean, bearing in mind that all these original theories, which actually still, you don't have to look very far inform a lot of thinking both inside and outside science, I would have to say, were arrived at before scientists had access to the brain. So, you could look at dead brains. You could, you know, weigh them or cut them up or, or whatever, or you could look at the consequences of disease or damage and conclude what was involved in language or movement, et cetera, by the effect of that damage. But you couldn't actually look at an intact living human brain and intact living humans. So I think that's an important thing to remember in these theories arrived before we had proper access to the brain.

[00:10:44] Anna: That raises an interesting point. You know, your book started in the 18th century because you said that that's when they kind of started to look to the brain, not necessarily at the brain, to explain women's inferiority, but before that, you know, these same scientists and philosophers, they might not have been thinking about the brain, but they were looking at other parts of a woman's body to place blame on her inferiority, whether that was the hysterical uterus or their nerves or their hormones, which your book gets into a bit. But it seems like there's just always something that the medical and scientific community are trying to use to prove this predetermined conclusion. Exactly. Um, as you say.

[00:11:24] Gina: Yeah. If you look at the history is it's, it seems to be a, quite a determined effort to weaponize women's biology against them, you know, to draw conclusions about mood changes and the vulnerabilities that the ability to bear children also brought. So the brain was part of that story, but it became the most powerful part of the story.

And in a way not having access to the brain meant that, you know, you could let rip if you like with more extreme theories, because although you dressed it up in some kind of scientific paraphernalia, so you could feel the bumps on the surface of a skull, or you could measure angles on the skull and draw conclusions about the shape of the brain inside the skull, it was clear that focus on the brain as accepted as the core basis of human success, if you like. You needed in a way to prove that women had inferior brains, because otherwise you would have to be challenging the status quo and existing power differential.

[00:12:24] Anna: Yeah, and it wasn't just scientists, but neurologists, psychologists, philosophers, anthropologists, biologists. I was just kind of blown away by how many different fields were trying to prove this.

[00:12:36] Gina: Indeed. That's right. And psychologists, in the same way that the brain sciences were trying to prove that the beliefs were based on scientific reality. So they said we can explain why society is structured in the way it is. And experimental psychologists were also trying to justify their existence if you like. So they helpfully weighed in and produced, you know what I call that go to list of well-known, in inverted commas, male-female behavioral differences. Again, with the assumption that this was something to do with the functioning of the brain, that they weren't able to look at, but were able to speculate that there was an association between a particular kind of brain and a particular kind of behavior.

[00:13:17] Anna: And now that we can look at the brain, can you summarize for us why you wanted to write this book? What is your kind of main argument that you present in the book?

[00:13:28] Gina: Um, I mean, as you've mentioned at the beginning, the subtitle talks about the new neuroscience. And I think as I was practicing neuroscientist and using emerging neuroscience brain imaging technologies to address particular issues as it happens, in developmental disorders. But what I was interested in is how brains get different, which almost invariably then draws you into the kind of male-female debate.

It was really saying that neuroscience has new things to say about the brain, and this means that we should revisit these old questions, these old certainties, see if we know what truth remained or, if any. You know, we need to use this new science better because, the answers that have been come up with we need to challenge these. Cause if we look at the research findings, they're not consistent. So that was part of it. The other part of it was the new neuroscience, right at the beginning, when we started having in the 1990s wonderful brain images, that really captivating all of a sudden, they were being shared, not just within the scientific community, but used very enthusiastically outside the scientific community. Sometimes by scientists, but sometimes by non-scientists who didn't quite have the level of understanding of what these pictures were showing.

And so they were also saying, oh, you know, we know that male and female brains are different, so they didn't challenge the question. So let's have a look at how these wonderful new images can prove this. So there was a lot of misuse, or, you know, a continuation of what I call the hunt the difference agenda.

[00:15:01] Anna: It just cut out a little bit. That last word, what you call the

[00:15:04] Gina: Hunt the difference agenda.

[00:15:06] Anna: hunt the difference agenda. Yep. Yep.

[00:15:08] Gina: So it was part of the whole package That these new images became the new thing and any discipline wanted to put neuro in front of it, you know, see what neuro philosophy and neuroaesthetics and neuro anything. And therefore neuroscience starts to get a bit uneasy and say, actually, that's not quite what we said. And, you need to be aware that these images aren't quite what you think they are, et cetera. So that was another part of the book to say, this misunderstanding has very profound effect on this male-female debate. In particular that we need to challenge this because it's not just a question of anatomy. We're not just trying to find what bit it is that would tell me or anybody that a brain comes from a man or the brain comes from a woman. We're asking the question, because we want to know about gender gaps.

And you know, if we're parents, does a female child have a different brain from a male child and should you therefore treat them differently, expect them to do things differently, encourage them to do things differently. So there's lots of kind of real life applications. And a lot of it was just, I, you know, I got fed up shouting at the radio you're driving along and somebody comes along with neuroscientists say, and you say, no they don't! So I thought, put your money where your mouth is and write a book and say what neuroscientists really say.

[00:16:26] Anna: So what do neuroscientists really say then? You know, are you arguing that there is no difference or, what's the kind of crux?

[00:16:33] Gina: Right. Well, yes. I mean, I'm not arguing, it sounds very odd and people think it's very paradoxical because they love to bandy around the term "sex difference denier", you know, in the same way as "climate change denier". So I, and people like me are labeled as sex difference deniers, I'm sure there are sex differences in the brain.

The argument has in fact, always been based on size of the brain as a whole cause there was the original story about men had on average and that's really important, probably should come back, to that bigger brains. So that's why they're superior.

[00:17:05] Anna: Because they have bigger organs right? They're just bigger all around?

[00:17:09] Gina: Well, that's right. I mean, we now know, we've got 30 years of brain imaging data and if you go through all of the data that's been collected in that time and, check on the reliability and replicability of the findings, et cetera.

There is nothing within the human brain with respected different sizes, structures, et cetera, which differentiates female brains from male brains. Other than that, on average, male brains are bigger, but that's because males are bigger. And their hearts, kidneys, liver, et cetera are also bigger. And if you correct for that difference, which you can do, then all these so-called sex differences disappear.

It's, it's a scaling issue. You've got bigger heads inside that bigger head is a bigger brain, and therefore some of the organs are bigger and some of the structures within the brain are bigger. And some of the connections between them are longer or whatever. But if you correct for all of that, then any differences that have been claimed in the past, and there are very many, disappear.

And I think that's a really important issue, but it's not to say that I don't think there are any differences. I think if you look at metabolism, if you look at how the human brain deals with different kinds of drugs, for example, there will be differences emerge.

But the other issue to be aware of is that we're not talking about absolute differences. We're not talking about all brains. Male brains are like this or all brains from females are like that. If you collect data on both brain characteristics on behavior, from a group of males and a group of females that the distribution of those data will be hugely overlapping. So it tells you nothing about an individual, which actually is probably what people really want want to know.

[00:18:46] Anna: to Yeah, we have a tendency. It's not just this challenge of getting scientists and philosophers to stop trying to prove women's inferiority, but it seems like just humans are just drawn to categorization, which we'll get into stereotypes and just differences. You know, there are so many more similarities between women and men, than there are differences, you know, we're all human first and foremost and the emotions and the needs and the desires that humans have are universal, but we always focus on what makes us different. And as you point out in your book, if you look at people within your own gender group, you'll find many differences. And if you look at people outside of your gender group, you'll find many similarities. And yet we continue to demarcate and define and constrict on the basis of gender alone.

[00:19:33] Gina: Yes, that's right. And I mean, categorization in a way is a survival mechanism because you do need to know, am I safe with people like this? And am I unsafe with people like that? So you need to find a way of sorting these. The brain, if you like, is the ultimate stereotyper, you know, because stereotypes are nice shortcuts.

You don't have to go through lots and lots of information every time you meet an individual, all you need to know is perhaps, three or four beliefs. I mean, you might be wrong, but you know, you might think this is a female blond Scott or something. Then, you know, you may already be bringing preconceived notions of what that person's going to be like.

[00:20:11] Anna: Yeah, I'm familiar with that one. Not the Scottish one, but the blonde.

[00:20:15] Gina: That's right. But I mean, the other thing to bear in mind is, again, we're not talking about absolute differences, but where those differences come from, because the early beliefs were essentialist beliefs, they were biologically predetermined.

So you just needed to focus on what was going on inside the brain. What we now know with the new 21st century neuroscience, is that what goes on outside the brain in terms of experiences that brain owners have or attitudes they encounter will also change the brain. And that, of course, when we're talking about stereotypes, for example, or expectations, gender gaps, that's a really important step forward because it was always assumed that if you found a difference, it was somehow innate or hardwired is another popular term, which of course has implications if you think we need more women, more successful women, we need more women in science, we need more emotional men. Again, stereotyping suggesting we don't have enough of those. So if you believe the its hardwired, then you know, what are the points of diversity initiatives? Because you could say, well, if somebody is like this, that's what they're like, you know, we could offer all kinds of training packages, but that is how they will continue. So that's another important aspect understanding where these differences come from, as well as what they are.

[00:21:39] Anna: We're definitely going to get into that a bit more of the stereotyping, the immense social brains that we have that starts at such a young age. But yeah, you point out in your book that the key issue is really looking beyond the simple category of sex, you know, just to not stop there, but to see what other factors might be entangled as well. Exactly, as you say. So real quick, just to make sure we're all on the same page here before we kind of move forward. When we talk about sex and gender, what do we mean by those? Can you just walk us through the differences?

[00:22:13] Gina: Yes. Well, two things I would use the term sex to apply to biologically determined differences, which are determined by the fact that, normally speaking and I use that caveat advisedly, you either have X, X, or X, Y chromosomes and associated with that are different levels of hormones. And together, those produce characteristic, biological differences between males and females. And I would call those sex characteristics. At the other end or somewhere else, if you like outside in the world, there are a whole range of attitudes, beliefs, expectations, social norms, et cetera, which are differentiated into male and female, masculine, feminine. Not at this stage getting into whether that's right or wrong, but that, that is the reality. Everything from, you know, the fact that there are single sex schools and you know, which again is an interesting issue to come back to.

So the world is gendered, and the origin of that term actually is interesting in that there wasn't a term gender, when this story first emerged, everything was assumed to stem from sex differences. So you had anatomical sex differences, sex differences in the brain, sex differences in behavior, sex roles in society. So there wasn't a term gender. It was assumed that sex applied to everything. In the 1980s, with the sort of rise of the second wave of feminism, there was a different move saying that we live in a society, which is differentiated according to sex, but that is wrong. Actually, these, that kind of socially constructed categories, and we should not call them sex categories, we should call them gender.

I think an aspect of it too, should be, why are we actually asking the question? Because a lot of people would just assume that different definitions apply to the whole issue in one fell swoop. If you're asking about physical illnesses, for example, then why do more women have Alzheimer's than men and why do more men have Parkinson's disease than women? So if you're looking at brain-based physical illnesses, then sex differences or sex influences are going to be important. If you looking at, sex or gender differences in mental health, much higher instance of depression, for example, in women or anxiety, much higher incidence of suicide in young men.

So that's another level of questioning. Or to the issue of gender gaps, you know, why are there so few women in certain branches of science? Why are there gender gaps across the world in a whole, you know, financial independence, educational achievement, health outcomes, et cetera. So I think that's another issue with respect to sex and gender, because very often the argument is assumed to apply to the whole issue. And I think that the differential balance is important to remember.

[00:25:08] Book excerpt: “Brains reflect the lives they have lived, not just the sex of their owners. Seeing the life-long impressions made on our plastic brains by the experiences and attitudes they encounter makes us realise that we need to take a really close look at what is going on outside our heads, as well as inside. We can no longer cast the sex differences debate as nature versus nurture - we need to acknowledge that the relationship between a brain and its world is not a one-way street, but a constant two-way flow of traffic.”

[00:25:45] Anna: All right, so let's get into these moles, which probably sounds like a really weird term to anyone listening, who hasn't read the book. So let's start there. You call these myths about the brain "whac-a-mole myths". So can you tell us what do you mean by that? And what's the most common myth or mole that we can go ahead and whack?

[00:26:06] Gina: The idea of whack-a-mole came up with the idea, a bit like me shouting at the radio, a lot of early research findings into, sex differences in the brain were based on very small numbers and there was all sorts of methodological issues and they became very popular when they came out, they informed pre-existing beliefs.

So we have this amazing confirmation bias where if somebody proves something, we already believe, we think that's fantastic. But if somebody shows something we don't believe, then there must be something wrong. So, very early findings, for example, the idea that women process language with both sides of the brain and men process language with only one side of the brain, kind of fit it into what people already believed, thanks to findings from neuropsychologists and experimental psychologist.

And so there are beliefs scientifically , which become firmly embedded . And then somebody comes along and says, do you know what actually that's, that's not true, we've got new techniques, we'd done a bigger survey. We've done a better controlled study. So actually we've moved on from that belief. But unfortunately that moving on within the scientific community, doesn't always get mirrored in the public consciousness. And whenever I see, that phrase "neuroscientists have proved that" my heart does slightly sink, as you think, how far back are they going or how recently are they looking at the data? So these are the kinds of moles, a bit like the fairground game. Whack-a-mole where a moles head pops up through a hole in a board or something and you whack it with a hammer and then it pops up in another hole et cetera. But anyway, the idea is that you never actually get rid of these things. They just pop up somewhere else, maybe in a slightly different guise, and that is so true of what goes on, particularly in the neuroscience of sex and gender.

And it's almost as though somebody says something which resonates so well or is so well publicized at the time that it becomes fixed. And no matter how hard the scientific community tries to do big multiple surveys and says, actually, that's not really the case, we thought it was initially, but it isn't anymore. It still pops up in a different guise and I mean, the biggest mole of all like is the idea of the female brain or the male brain. I have given talks called, the female brain is dead, long live the female brain because you can walk people through how the early beliefs about the origin of the female brain, have turned out to be past their sell by date, if you like, and we need to update our thinking, but people won't do that. And you then turn to, or you get sent some notification about an article in a business magazine, you know, "the female brain, how to harness the power of the female brain" and a lot of conversation about leadership during the recent pandemic where people were saying, countries with female leaders were doing better then countries with male leaders and this is power to the female brain kind of thing. And you think at one level, well, isn't it great that they suddenly start thinking the female brain is in some way superior, but actually the science doesn't support it. So, you know, you have to say I'm, sorry, it's a nice idea, but it's not true.

[00:29:18] Anna: Why didn't they have these ideas before, before we had all the science?

[00:29:22] Gina: Indeed yes, I've come across it really recently on websites of training academies or private education institutions or coaches of some kind, saying we need teach boys differently from girls or train males differently from females, et cetera, because their brains are different and they process information differently. So those are the kinds of moles that the book is trying to work whack.

[00:29:48] Anna: So we should all be on high alert. The next time we see an article like this claiming anything about...

[00:29:53] Gina: Well that's right, and I mean I have written with colleagues, we've done a sort of eight things you need to know, which is really when somebody says this, make sure you know, the backstory, which of course, you know, it's all very well as a scientist who actually loves going off and looking at different references and things.

But if you're, you know, a parent or an education or an employer or something along those lines, then you probably do need to check how valid this wonderful headline is. There's very often the headlines "at lost the truth" or "proof at last", because it reflects very much what appears to be a very fixed or well embedded need to believe that male and female brains are different. And that means we can carry on doing what we've been doing for many, many decades, centuries, even.

[00:30:43] Anna: Yeah, just kind of an excuse to validate anything that is not right. Anything that's unfair in the system, well, men and women are different. So I actually, heard an interview with Cordelia Fine yesterday, who you mentioned throughout your book, who talked about how even though we have kind of these traditional views that are falling away, they're being replaced by these seemingly more liberal views, this kind of "separate but equal". Everybody should have equal opportunities, but it just so happens that men and women choose different kinds of opportunities and kind of falling back on essentially the same argument.

[00:31:21] Gina: The issue of choice and preference, I find it very interesting because I'm passionate, as you probably picked up about the under-representation of women in science and the suggestion, certainly the early suggestion that this was a competency issue. You know, women didn't do science because they couldn't.

And now it's slightly shifted because we still have the gender gap, there's a vast under-representation of women in science generally, but in certain sciences in particular and worryingly the kind of sciences, which will determine our future, like robotics and computer science and physics.

And people are saying, oh, well, okay, it's not competence, but it's actually has to do with preferences and choices. And these are, you know, due to endogenous factors. I think I've seen it described some ways new entry in an old playbook, which again gives somebody free reign to say, well, let's not waste time, encouraging women into science because constitutionally, they don't want to do it.

And we don't want science full of unhappy scientists. It's something people really want to believe. And it's a very difficult belief to shift. I mean, and probably what you need to do is say actually this would be a better way of looking at the human race. Dividing the human race into males and females, has not proved a hugely informative enterprise so far.

[00:32:42] Anna: Yeah. So let's get into that more with scientists cause you did dedicate a good amount to this and that kind of stems into the stereotypes. You know, there's obviously the stereotype that all scientists are old, male, bearded and bald. So can you help us understand?

[00:32:58] Gina: And white

[00:32:59] Anna: and white. Um, can you help us understand, you know, if it's not, what is claimed by and has been claimed by others through the centuries, where do you think this gap comes from?

[00:33:15] Gina: If you look at countries who have the smallest gender gaps, like the Scandinavian countries and Iceland, proportionally, the under-representation of women in science in those countries is greatest. And you think that's a paradox that can't be right. You know, because science has leveled the playing field and I quote, and this is where the idea is that, despite this level playing field, women are still choosing not to do science there must be some kind of essentially predetermined rationale behind.

And what I would say is that we really need to look at science and just check how level that playing field is. And what you're seeing is very much, you know, what people have already observed in business organizations or politics, for example, in that you get the maintaining of, you know, people like working with people who look like them, or, you know, who they feel comfortable with, et cetera. So, you know, the basic origin, the lack of diversity and in so many institutions.

As well as you know, from early on, particularly in science, for example, once science became sort of professionalized, women were actually excluded, deliberately excluded that Royal Society didn't allow women to be members for hundreds of years after its establishment, and things like the Nobel Prizes, et cetera.

So I think that what we're really saying within science is that there's all sorts of biases within science, which are exactly the sorts of biases we know will affect the brain and how the brain functions and how comfortable somebody feels in their environment. You know, if they belong, where they don't belong, if their successes or acknowledged or underplayed or ignored. So I think that the observations about science perform a nice case study about how the outside world or the culture within an institution, if you like, can have exactly the sort of brain changing effects that different hormones or different synaptic patterns of connectivity can have.

[00:35:13] Anna: Yeah. And you say brain changing patterns, which I want to get into next, how our brain is shaped by the world, around us, throughout our life from a very early age, but real quick, on the point you made about the Royal Society, I have written down here cause I thought that that was a fascinating point. So it's an academic society for science here in the UK. And it was founded in 1660, but didn't admit its first female member until 1945. And this was after one woman was denied entry in 1902 because she was married. So she couldn't be regarded as a person in the eyes of the law. Uh which, yeah, that, that would make it a little hard to get involved in science I'd say.

[00:35:52] Gina: Yes, indeed. I mean, those kinds of things characterize quite well, you know, people were saying, you know, no women have won the Nobel Prize, et cetera, are you really surprised? Um, but now we know that our brains are wired to make us sociable and belonging sense of belonging is a very powerful driver and a lack of self esteem linked to this sense of not belonging is also a very powerful driver of human behavior.

You know, almost as profound as the search for food and drink and sex, if you like. In a lot of the mental illnesses, you can see, uh, disorders of self-esteem. And if you look at mortality rates and things like eating disorders, for example, self-image problems, you could say that that actually self-esteem is perhaps one of the primary drivers of human survival.

And that's, you know, putting it in a very extreme way, but it means that organizations and institutions really need to look at themselves really carefully to say, you know, it's not just about diversity, it's also about inclusion, you know, it's not just getting more people, different sorts of people into the organization. Those people have got to be included, and that may mean fairly dramatic changes in the institution's behavior and reward systems, et cetera.

[00:37:13] Anna: Hmm. Yeah. You've had some really, kind of surprising information about self-esteem and self silencing and the book, which we kind of do know that women have a tendency to do that, but the extent to which, you wrote about these thousands of research papers across the world that had the same findings about women having lower self-esteem than men and being a lot more likely sacrifice their own needs and not state their own feelings to, you know, avoid conflict and make sure nobody else feels uncomfortable.

so I guess on that point real quick, I'd love to know, you know, with your neuroscientist hat on, why is this the case? You know, is it because I could, I could deduce that if women are fed all of these messages, both overtly and more subtly throughout their lives, then they do begin to believe them and doubt their abilities and it kind of becomes a self fulfilling prophecy. Is, is that kind of what happens?

[00:38:06] Gina: I think that's, exactly. Certainly one of the pathways to self silencing. I mean, there's a great phrase again, which I talk about in the book by Reshma Saujani who founded Girls Who Code who's very anxious about the under-representation of women in computer science.

And so started making sure that schools had afterschool computing clubs for girls, et cetera, but she has this phrase, " We raise our boys to be, brave and our girls to be perfect." And I think that sums up so much of the behavior and self-belief shaping power of gender stereotypes. I think that's, that's a really important thing for people to be aware of because, you know, you can get into arguments about toys and reward systems and things, and, well, toys in particular, people roll their eyes and say, oh, you know why shouldn't little girls dress up as princesses and boys have all the construction kits, et cetera.

And that, that is to do with the fact that, you know, from day one, whole day zero, if you like, when babies arrive in the world, they are highly tuned to pick up social cues. And if little girls are told not to make a fuss, to sit still, they're rewarded when they get things right, that will shape their behavior because our brains desperately want to pick up the rules of behavior from the outside world to ensure that their owners fit in. And therefore, women much more than men are encouraged to be conformers, not to rock the boat, not to be, you know, not to strike out on their own and be a wild card in the pack, and think that's a really, for me, something that people really need to be aware of.

[00:39:51] Anna: Yeah, that was definitely one of the most fascinating things in your book for me was just how early we're influenced by our surroundings. You know, everyone assumes babies are these helpless little humans, but as you put it, you said that they are actually "highly sophisticated rule, hungry scavengers who with their plastic, flexible moldable brains are focused much more than we ever knew on learning the rules of social engagement in their world. And they start very, very early."

[00:40:20] Book excerpt: “One of the first, one of the loudest and one of the most enduring social signals a baby will pick up on is about the differences between boys and girls, men and women. Messages about sex and gender are almost everywhere you look, from babies’ clothes and toys, through books, education, employment and the media, to everyday ‘casual’ sexism.... We must remember that our childrens’ developing social brains will always be on the lookout for the rules and expectations that go with being a particular member of a social network.”

[00:40:56] Anna: You say babies come into the world with unfinished brains and you call children gender detectives. So can you just walk us through a bit more of how we see this social brain evolve through childhood, and I guess the "pink is for girls blue is for boys". That was another whack-a-mole myth in the book.

[00:41:16] Gina: Yeah, indeed. Yes. Yes. That's right. The pink and blue tsunami. Yeah. The key issue is, again with respect to trying to explain to people that this essentialist argument is not the answer. You know the people would say, well, children are gendered from such an early age. You know, my little girl, from the age of three or four, always wanted to wear pink. And my little boy played with tractors and there's always these stories about little girls are given a tractor and they tuck it into a cot and push it round in a pram or boys cut their piece of toast into the shape of a gun or something.

And so that's held up as a kind of gotcha type message, you know, we are terribly open-minded and gender neutral, but our children fall neatly into these categories and therefore they must be predetermined. And I think it's because people didn't realize that because as you say, human babies are physically and cognitively actually very undeveloped when they arrive.

But one of the key things for survival is that, we need to be aware of our in-groups, you know, where's our food gonna come from, who's going to rescue us, et cetera. So you need to pick up very, very early on, key features about the people around you. So, within very early days of birth, children are responding differently to the sound of a human voice, as opposed to, uh, abstract sound, to the sight of their caregivers, opposed to a random individual or to a face as opposed to a scramble image.

So they're spotting differences from very early on. And of course if the differences are given different kinds of value and a coded differently, that starts to emerge a bit later, but children are very good at it. So, the whole pink and blue thing with quite young children, you can take neutral objects like I think the melon baller and the garlic press those kind of things for some reason. And if you paint them pink or blue and then gives them to quite young children and say, which of these do you think girls would play with? Which of these do you think boys will play with? They will neatly sort them into pink for girls and blue for boys.

So they've already cottoned on to this coding system that particularly in the 21st century, I think is very profound. I talk about gender bombardment in the 21st century. And I think there is a lot of it, a lot more of it, particularly because of social media and kind of 24 7 information input. So people who look at little boys and girls and say, well, you know, the little girls are always walking round the dressing up box. And the little boys are always wanting to be racing around the playground, what you need to ask yourself is, is, is that true of all boys and all girls? And assuming it is means, you know, you might well be missing out on the quiet little boys who'd rather do dressing up, or the girls who'd rather be racing around the playground.

And you know, has this sprung automatically, or could it be the response to how society treats them and what they're rewarded for? If little girls are rewarded for sitting quietly it's more likely that that's what they'll do. Whereas if it's assumed that boys will automatically run around more and make more noise, then that's more acceptable for boys to do so they will pick up on that as well.

[00:44:29] Anna: And when you see that three, four year old running around doing that, they've already had three, four years of that socialization, which we, we don't really think about because we realize it starts so early, but they've already been exposed for years.

[00:44:43] Gina: Yes, that's right and there's a study I talk about, which is up to the age of about two, boys and girls will pretty happily play with whatever there is in front of them, bearing in mind of course, it certainly early on, they don't choice. They are given a toy play with, you know, so somebody else who's making the decision for them. And about the age of two is when boys start rejecting things that are pink, and girls are much more likely to play with dolls and things like that. So by the age of two children have already picked up on the fact that there's items that it's acceptable for them to want to play with or items that it's not acceptable for them to play with.

That there was a survey done last year by Lego, which looked at the effect of stereotyping and toys. And one of the findings was that boys are much more likely to be discouraged from playing with toys, which were in, in brackets for girls, you know, who determines for boys and what's girls, whereas it didn't matter as much for girls so there is imbalance kind of built in how the world works from a very early age.

[00:45:47] Anna: And it really matters, you know, you wrote, this is a quote from your book, "the kind of toys that children play with can have significant effects on the kind of skills they may develop or role-play they will indulge in. So any process which narrows the choices for either boys or girls should be viewed with alarm."

[00:46:04] Gina: Yes, I think that's right. And I mean, the example I tend to use a lot is construction toys and coming back to Lego, in fact, and spacial abilities, is a very powerful skill, which allegedly shows robust, in inverted commas, sex differences in that in lots and lots of different tests of spatial ability, males tend to on average do better than females and that's has been jumped on as an explanation for the under-representation of women in science. Coming back to that again, because spatial thinking is a core part of almost all of science. So if constitutionally you find spatial manipulation problematic, then you are less skilled in that area. And it was assumed that that was a fixed, hardwired brain-based difference.

But we now know, again, coming back to 21st century neuroscience, that you can actually change those skills, even in an adult, it's not just to do with children so that you could take individuals who find spatial manipulation tricky, you can train them to improve their spacial abilities, and you can generate that that also affects their skills.

So you can demonstrate that they're better at spatial thinking and that their brain structure and function has changed. So I always use that as a really nice example of how what looks like a sex difference is actually just a training opportunity difference. And more recently, there's been some studies looking at children playing a collaborative play with dolls and doll houses, et cetera, and showing that the social parts of the social brain are more activated with those kinds of play scenarios. So that's another area where what we play with as children can have pretty profound effects on the kind of adults we turn out to be.

[00:47:57] Anna: Yeah. You said "brains reflect the lives they have lived, not just the sex of their owner". And it's not just our brains that are plastic and changing, but our hormones too. I thought this was another fascinating part in your book where you talked about the changing testosterone levels in men and how the testosterone levels actually decreased for men when they spent more time with kids. Can you just tell us about that real quick and the wider implications of it?

[00:48:25] Gina: Yes. Well, I think the issue is that very often people will say, oh yes, brains that in a kind of dismissive way. I think if you've made a good argument that brains on different than we'll find something else. So they come back to hormones because in the 20th century hormones were a much more when I talk about weaponizing biology, raging hormones were at quite a powerful argument in that particular sphere.

And there is this idea based very much on studies with non-human animals. And I think that's an important distinction, that we are, I mean, hormone means drive to action. So the idea is we are driven by our hormones and therefore, you know, high levels of testosterone will equal possibly lots of self-confidence and success or possibly lots of self-confidence and aggression. Um, and similarly estrogen will make you nurturing and caring and collaborative, or behave in a particular way in the reproductive process, if you like, if you're a Guinea pig or a mouse, um, but that's kind of been extended into human society.

And what's interesting in terms of human social neuroendocrinology is that we know that hormone levels are again responsive to what goes on outside the brain, it's not just an automatic response to a particular phase of estrogen cycle or a particular site of a fertile female, for example. And that the social context, for example, the example, you mentioned that if a father is a primary carer of a newborn baby, testosterone levels are lower than if a father is not the primary carer of a newborn baby.

So the kind of social context of being a new father is the same, but the extent of your contact with the new baby will be reflected in changing hormone levels. So it demonstrates that again, rather like the brain responding to what's going on in the outside world, so do hormones. And I think that's important to remember in humans, because very often, and to come back to Cordelia Fine, again, she talked about in her book Testosterone Rex, really unpacking the story behind testosterone being the profound driver of all sorts of differences in male behavior and feeling that it's time to say that that story is, has outlived its usefulness, as Tyrannosaurus Rex, for example is now, uh, extinct. So that's an important thing to remember. We're talking about human beings. We're not talking about Guinea pigs and mice and zebra fish and things.

[00:50:52] Anna: Yeah, that was really an interesting point because we don't think about testosterone levels kind of fluctuating like that in that way based off of our immediate environment. And, yeah, that was very eye-opening. And, and speaking of men, a recurring segment of this podcast looks at all the ways, these issues impact men.

[00:51:14] Overdub: “And now for: “men are losers too”... in gender inequality of course. These are not "women's" issues, these are everyone's issues, because as long as women are held back from their full potential, so are we all.”

[00:51:28] Anna: So I would love to know how are men negatively impacted by this persistent myth? And what do you think they stand to gain by doing away with it?

[00:51:39] Gina: Well, the key issue for males is a bit like, you know, to come back to the, we raise our boys to be brave and our girls to be perfect. The expectation that as a male, you will be courageous, independent, a leader in success, et cetera, et cetera is very high expectation to live up to, and also slightly more nuanced expectations that, you don't express your emotions, that you know, in England you talk about stiff upper lip, but generally the feeling is that your somehow male behavior manages to suppress emotions or to ignore emotions or to overcome emotions.

You know, the idea that being emotional is somehow suboptimal, and it's used, you know, women are emotionally labile in a dismissive sense of the word. So I think that has major impact for how men can behave in the outside world for how they believe they can behave, and how they can interconnect with other people. And as I say, you know, you've only got to look at the incidence of suicide rates among young males, to see that, you know, that particular stereotype is not serving them well in the way that affection is not serving girls well.

[00:52:54] Anna: Yeah, you call, You said that stereotypes were straight jackets for the brain, and that obviously will apply to their brains as well. And

[00:53:03] Gina: Indeed. Yeah, I think that's that's how I described the effect of stereotypes, and also the power of culture, because we've always assumed that evolution is a response to some kind of biological change. And so we look at how we have evolved due to biology, responding to the environment, but we haven't looked at really at what happens when the environment doesn't change.

So we have this amazingly wonderfully flexible biology, but if it's embedded in the culture, which never changes from generation to generation, then biology will obligingly that reflect that. So, you know, people talk about evolution and systems staying the same as they always have from generation to generation, but they never say, well, you know, has the culture changed, from generation to generation? And if it hasn't, maybe that's something to do with the fact that certain beliefs, certain attitudes, certain expectations are maintained..

[00:54:00] Anna: Yeah, I love that. And I always, I tend to quote Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on this which is that culture doesn't make people, people make culture. And I think that's something we lose sight of quite a lot as society.

[00:54:14] Gina: That's right. And particularly in the human society, because culture has such a profound effect.

[00:54:19] Anna: Definitely.

[00:54:20] Overdub: “The term ‘influence’ would seem to be a much more accurate reflection of the role that biological sex can play in our brains’ journey through life. Sex definitely matters; this is not an ‘inconvenient truth’ but it is a truth that needs to be carefully revealed. We need to go ‘beyond the binary’, to stop thinking of ‘the male brain’ or ‘the female brain’ and see our brains as a mosaic of past events and future possibilities.”

[00:54:51] Anna: So, so what's it going to take to finally whack all these moles and move forward, what needs to happen to resolve this matter once and for all?

[00:55:02] Gina: Yeah, I mean that is the hundred million dollar question or whatever, wouldn't it be? People talk about gender neutrality and, you know, parents talk about raising their children gender neutrally etc and you think well, good luck with that. But, I think my answer to the conundrum is gender irrelevance. I think we really need to sort of major revolution where being male or female is actually a very minor part of societies' assessment of individuals.

Because I think we have to offer somebody, offer the world, if you like something else, rather than just say, don't think of people as male or female. You will need to categorize them. We should have a better category system. We should get rid of whether you're male or female as being really, really important other than at a biological level, with respect to who can bear children and who knows how that's going to change in the future anyway, but you should say, you know, what does society need to function better than it currently does?

And let's, you know, organize people in terms of those particular kinds of skills. So we have people who are, who are really empathic. Maybe let's have a look at, you know, if empathy is a good thing, who's naturally appears to be naturally empathic. How can we make sure that other people become more empathetic? So those kinds of skills become much more celebrated and rewarded and encouraged in society. And I think that's the only way we're going to get rid of this kind of very strict binary, Mars and Venus type thinking.

[00:56:40] Anna: Hmm, that doesn't serve anybody, yeah. I think that's a really good point that we need something to replace it with. Cause I was thinking about that as well with just the myth generally that there is a male female brain in addition to just kind of making gender irrelevant that we need something to replace that because you know, if people see differences, they're gonna fixate on that and need something to explain it.

So I feel like, can we just find a way to change the public discourse to, um, you know, until we get to gender or irrelevance, which I feel like will just take a longer time that men and women may exhibit different characteristics, but it's much more socially influenced than biologically.

[00:57:23] Gina: Well, I think education, particularly early years education. I mean, then you can't say to a teacher in the middle of a class of 35 five-year-olds, treat each child as an individual, which of course is really what you'd like to do. Teachers will have some kind of grouping algorithm, if you'd like, just, you know, in order to survive the day. So, you know, look for different things in the children that you're teaching. And it may be in certain headings, but don't assume that all boys are like this and all girls are like that, because

[00:57:55] Anna: Yes,

[00:57:56] Gina: That way, you know, and I, I wouldn't like to disparage what teachers do, but, but they are part of the problem. Because you know, they reward girls in one way and boys in another.

[00:58:07] Anna: Because of course they've been raised in the same system, so it's a continuous...

[00:58:12] Gina: indeed. Yes, that is the major problem, we've got this self-fulfilling prophecy aspect, which is somewhere we need to break the cycle.

[00:58:20] Anna: Yeah, and we've gotten it at an individual level and at a systemic level. So that's quite challenging. And one more question on the future. Cause I liked at the end, you talked about intersex people and redefining sex altogether, and we've just mentioned making gender irrelevant, but also the possibility of a future with lots of genders, you know, at least five, if not more.

And also saying that in the 21st century, psychologists and neuroscientists are beginning to question the question asking, have we spent all this effort looking at two separate groups who aren't actually different and may not even be distinct groups, which is just, you know, I can see a future scenario where they're looking back and they're saying, wow, can you believe they used to put people into these two different groups? Um, So, so for anyone who might be hearing that line of thinking for the first time, can you explain how, how that's even a possible question? And what do you think the future looks like? You've kind of already touched on that with gender irrelevance, but I guess in terms of a multitude?

[00:59:22] Gina: Yeah. Well in a way, I mean, it's a bit like the classic sort of paradox, what we really need to do is not think about gender by thinking about gender a lot. I think what I was anxious to demonstrate in the book was that we need to break that previously inextricably, fixed link between sex and gender.

So the idea was that, you know, your biology determines your gender. And I think that's a link that needs to be broken. So currently biological characteristics that you acquire via your genotype gives you a particular role in the reproductive process. Cut it right back to basics. And that's the role of that particular part of the view. The rest of it shouldn't, I mean, for some people, their biology, their physical appearance is very important. It may be very much a reflection of society, but for whatever reason. And so that will be a primary part of, you know, if you ask somebody to describe themselves, they might say, you know, I'm tall and blonde and whatever. But for other people, what their biology is being male or female, it's irrelevant.

And, you know, they, they're attracted to particular kinds of people. Maybe the same sex may be different sex. They like to wear different kinds of clothes or whatever. So I think the future would be really important to say, first of all, it always used to be assumed that could only be two genders because they were firmly fixed to there being two sexes.

If you break that link, then there can be as many genders as you like. And I think that will be really important. And I think that there is a lot of us, you know, hot topic, the whole issue of transgender individuals, and some extent I think that we're looking at the consequence of this continued emphasis on a very fixed link between sex and gender. Deterministic one way link between sex and gender. And I think a misunderstanding of where that came from and how flexible it is is the basis of a lot of anxiety and argument in the 21st century around that area. And I think if everybody could agree that that link could be broken, then we might have a much better way of resolving what are pretty fraught issues around gender in the 21st century.

[01:01:52] Anna: I like that idea. Just breaking that link and it is extremely complex. I looked at the article in Scientific American that you mentioned that kind of illustrated the biological determination of sex. And oh my God, the fact that we arrived at just two categories when it is so complex, I'll put it in the show notes so everyone can go have a look at it.

[01:02:15] Gina: Yeah. I thought that was very interesting because lots of people would assume that the biology equals two sexes is a given, you know, and we don't even need to look at that when you actually look at that, you think, oh my God, how do we ever arrive at that? And even within the two broad categories, you can see how much variability there is.

[01:02:37] Anna: Absolutely. So is there, is there anything other than buying your book and looking at the Scientific American article and, um, is there anything that we can do as individuals?

[01:02:49] Gina: Yeah. Well, I think with respect to stereotypes, particularly in the early years, you know, call it out. I think it's interesting that there was quite a lot of interest in Lego last year, saying that as a result of their survey, they were going to stop gendered marketing. You know, they acknowledged that they were marketing Lego to boys and different kinds of Lego to girls.

And the results of the survey made them say, we are not going to do this anymore. And the French government has in fact legislated against gender toy marketing. So the people are starting to wake up to the consequences of stereotyping. And the, you know, within organizations there is attempt, you know, people talking about unconscious bias, big diversity initiatives, but, you know, to come back to something I said earlier, organizations need to make sure that it's diversity and inclusion, not just numbers, tick boxes. But I think to be relaxed and allow people to express their true selves rather than to assume that a particular label will tell you everything you need to know about somebody, because it won't.

It becoming a matter of public discourse, which is great. There is a lot of pushback. There's still a lot of "let boys be boys". There's a lot of religious input into the argument. And in days of uncertainty as we're living in at the moment. People don't like to be challenged with respect to something they thought wasn't an issue, not a matter of a debate kind of thing. So I guess uncomfortable ride, but, at least the discussion is being had.

[01:04:18] Anna: Absolutely. Is there a one-liner that you could give us for the next time we hear someone claim one of these whack-a-mole myths?

[01:04:27] Gina: Well, I think that a gendered world produces a gendered brain, you know, when people say all girls like to dress up as pink princesses, you know, it is, have you actually looked at any social media, the kind of stuff that children are being bombarded with. So, it's not a one-liner know.

[01:04:46] Anna: I think "a gendered world produces a gendered brain". I think that's a great one-liner. You can tailor that to the conversation, but I think the idea behind that really says it all.

If people take one thing away from this conversation today, what would you want it to be?

[01:05:04] Gina: There's no such thing as a female brain, or steal Reshma Saujani's, you know, "we raise our boys to be brave and our girls to be perfect" and, you know, ponder the consequences of that.

[01:05:15] Anna: Yep.

[01:05:16] Overdub: And now for: “Your Story”, the part where you are invited to reflect on this story as it relates to your own life - think about it, write about it, talk about it, and if you wish, share with the community. Whether or not you are listening in real-time, if you send in your thoughts, experiences, questions, and recommendations, they may be included in a future listener-led episode. Check out the link in the show notes, or revisit the Your Story episode, to learn more. Remember, no matter your story, you are not alone in your experience, and there is power in our collective realisation of this.

[01:05:58] Anna: So as listeners come away from this hour with you, are there any questions you want to put forth to them? Anything that they can pay attention to as they go about their lives or other ways they can reflect on their own experiences?

[01:06:12] Gina: Do you think we live in a gendered world, um, go into a bookshop, clothes shop, toy shop, supermarket, and just kind of raise their awareness of, you know, even the shower gel is gendered as I've noted in a supermarket. You know, have you encountered in your workplace, your school, your children's school, whatever, have you come across any examples which you now would think, we should have some different examples, you know, are there lots of pictures of male scientists on the wall, in your school science lab. Did you take your children for Santa Claus Lucky Dip at Christmas and find there was a barrel for girls and a barrel for boys,

[01:06:55] Anna: I might have to Google a Santa Claus Lucky Dip after this, but, uh, assuming our British listeners will know what you're referring to there.

[01:07:03] Gina: They will indeed. They will indeed. Yes.

[01:07:06] Overdub: And now for: the “feminism gets a bad wrap because the narrative has been just a bit one-sided" corner.

[01:07:14] Anna: All right. Now, for some rapid fire questions to wrap up, these are the questions that I ask every guest at the end. So, what does feminism mean to you?

[01:07:23] Gina: Feminism is about, I think it's about equality and equity. The term obviously has got it tied just to issues for women. But I think overall, feminism is a particular branch of a very much needed fight for equality of opportunity and equity of outcome.

[01:07:44] Anna: What is one of your earliest memories of gender, a time that you realized the world didn't treat girls and boys the same?

[01:07:54] Gina: Oh gosh.

[01:07:57] Anna: Or a significant one.

[01:07:59] Gina: Yeah, I mean, I have to say I have a, a male twin. Um, so we were kind of

[01:08:07] Anna: So pretty early on?

[01:08:11] Gina: Yes, but oddly, because we were twins, there was quite a lots of family treat us the same. So that, which was interesting. I don't have any other male or female siblings. So, you know, I didn't know if boys were allowed to do things more than girls or girls were encouraged to different things.

But we were certainly given different toys at Christmas. Certainly I did actually ask for a cowgirl outfit, one Christmas. Cowgirl, so, you know, I was already indoctrinated, but actually I got a princess outfit, so yeah, that's perhaps one of my earliest memories

[01:08:47] Anna: Well, it's great that you have to think so, so hard on that one and you guys were treated with it that way. Um, what is the story of woman to you?

[01:08:56] Gina: Story of a group of people who've been ignored, treated as invisible, interruptable uh, incompetent. The four I's, if you like. Um, for no good reason. Assuming we're talking about the story of woman going back over centuries, for example. Yeah. A group of people who've been unfairly treated.

[01:09:17] Anna: All right. And what are you reading right now?

[01:09:20] Gina: I'm one of those terrible people that have about five or six books on the go. And sometimes I get books sent to review. So what I'm actually reading at the moment is not actually published yet. So I'm probably not allowed to tell you...

[01:09:34] Anna: that's all right. You're reading, a very new book. Well, we can . Leave it at that.

[01:09:41] Gina: it's yeah, I thought I could tell you it's called Different: What Apes Can Teach Us About Gender. So it's a primatologist trying to extrapolate observations about monkey, literally monkey behavior and monkey societies, to suggest that it brings us understanding about gender in human society.

[01:10:03] Anna: Wow. That sounds fascinating. Who should I make sure to have on the podcast and it's okay to be aspirational.

[01:10:11] Gina: Oh right. Anne would be my nominee.

[01:10:17] Anna: All right.

[01:10:18] Gina: Um, she's a biologist who has probably done more than anybody else to try and help us understand the relationship between expectations and biology, so she's great.

Cordelia Fine? Obviously I've already mentioned her.

Daphna Joel. She's from Tel Aviv and has done a lot of work, on really producing the data to show that there's no such thing as a female brain, that every brain is different from every other brain and our brains are a mosaic of different parents sticks. Lise Eliot from Chicago, she wrote a wonderful book called Pink Brain Blue Brain, which is very much a focus on early stages and how small differences can be magnified by external influences.

[01:11:05] Anna: What are you working on right now?

[01:11:07] Gina: I'm working on is potentially a second book, which is about, gender and mental health issues, which is an extension of what I mentioned, you know, about the much higher incidence of disorders such as depression and anxiety, and self-injury, eating disorders among females, which is very often allegedly proof of some kind of biological vulnerability, but to say, how might what goes on in the outside world produce those kinds of problems as much as biological vulnerabilities. And it's tied a bit to the idea of, you know, our culture is like a straight jacket so for some people straightjacket can be very harmful.

[01:11:48] Anna: Oh, well, maybe we'll get you back on here one day when that is out, because that sounds right up our alley.

[01:11:54] Gina: Excellent.

[01:11:55] Anna: Uh, and then last question, and this will be in the show notes as well, but where can we find you?

[01:12:00] Gina: I've got my own website, which is, Gina Rippon one word.com. My Twitter handle is at Gina Rippon one. I don't do Facebook. And I'm not very good at at LinkedIn. I mean, I have a university website, obviously. So if you went to Aston university, you'd find me and my doings there.

[01:12:20] Anna: Well, thank you so much for your time today. It was a pleasure.

[01:12:27] Gina: Good. I'm glad we sorted out the early technical problems.

[01:12:30] Anna: Yes, we persevered. So thank you so much. It's been, um, it's been wonderful Professor Gina Rippon. Thank you.

[01:12:38] Overdub: Thanks you for listening. The Story of Woman is a one-woman operation, with voiceovers done by Jenny Sudborough.

If you enjoyed this episode, there are a few small things you can do that make a big difference in helping other people find the podcast and allowing me to continue putting out new episodes! You can subscribe, leave a review, share with a friend, follow us on social, buy me coffee (not literally - this is the name of the platform to raise production funds - but hey, I’d grab a coffee as well), or head to the website and check out the bookstore filled with 100's of books like this one. If you purchase any book through the links on the website, you support this podcast - and local bookstores! Soooo feel free to do all your book shopping there! All of these options are in the show notes.

Anything you can do is appreciated and makes a big difference in elevating woman from the footnotes of history to the main narrative.

💌 Sharing is caring