[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Overdub: Hello, welcome to The Story of Woman, the podcast exploring what a man-made world looks like when we see it through her eyes. Woman's perspective is missing from our understanding of the world. This podcast is on a mission to change that. I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein Lau and each episode I'll be speaking with an author about the implications of her absence - how we got here, what still needs to be changed, and how telling her story will improve everyone's next chapter.

[00:00:34] Section: Episode level introduction

[00:00:35] Anna: Hello. Hello friends. Welcome back. I am so happy you are here. We've got a fantastic conversation for you today about women innovation and the economy. Did you know that it took us more than 5,000 years to attach wheels to a suitcase? Did you know that there was an entire electric car industry a hundred years ago with electric buses, fire trucks, and taxis in many of the world's major cities? Did you know that the first computers were actually not machines, but women? Or that the existence of bras allowed us to get to the moon? Probably not because all of this has to do with women. And we have a tendency to ignore women when it comes to the economy.

But as my guest points out today, our entire world, and the economy that's in it, is shaped by gender and by the deeply held beliefs we have about the role of men and women in society. It can help explain why women receive only 3% of venture capital funding globally, and why there isn't a single country on the planet in which women collectively don't have less money and less economic opportunity than men. And why the 2008 credit crunch may have held the world economy back for 10 years, but the ongoing female credit crunch has been holding the world economy back since well, forever. And why it took us more than 5,000 years to attach wheels to a suitcase.

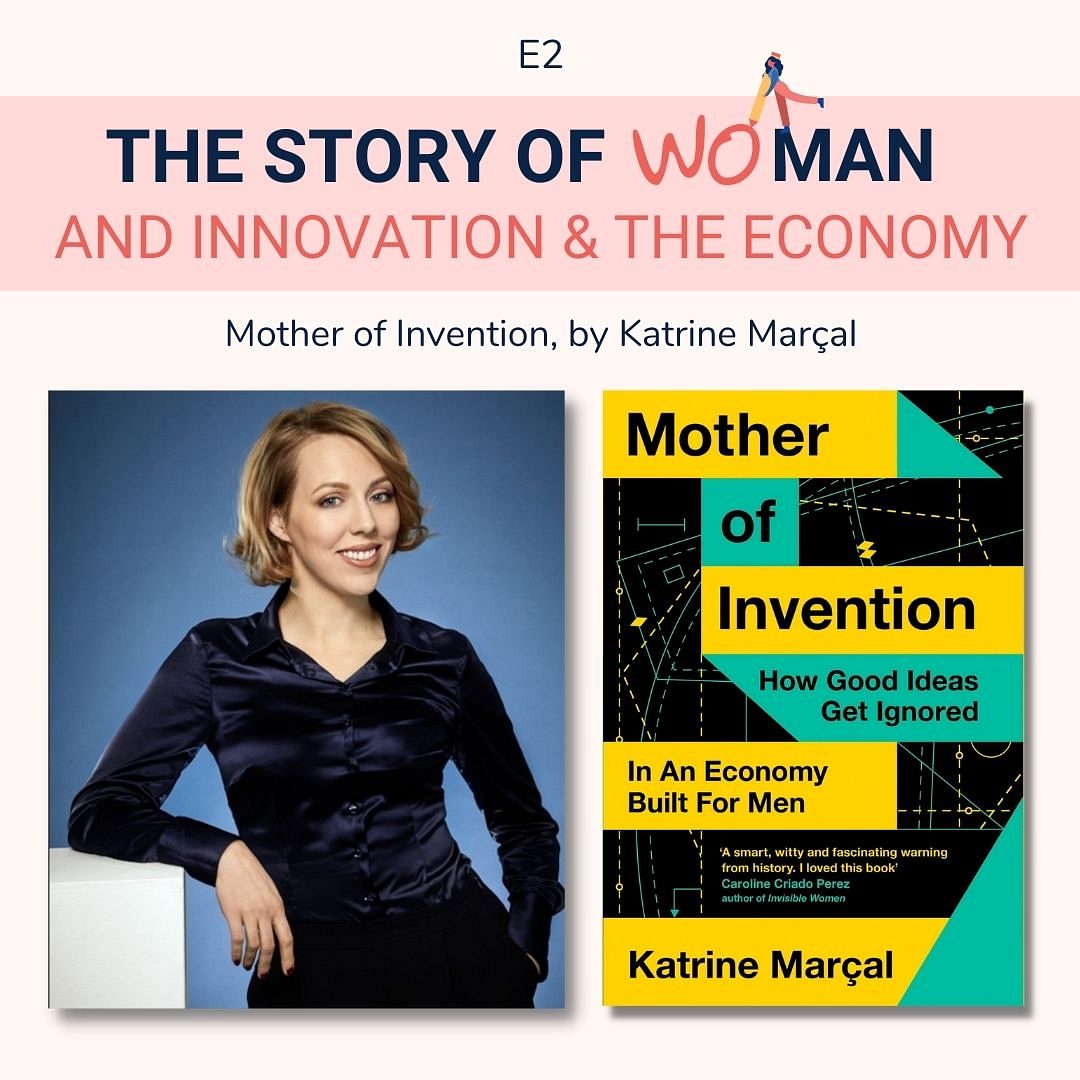

Our ideas about gender, and the fact that men have money and women don't, are factors that fundamentally shape, and hold back, our world. But it doesn't have to be this way. Katrine Marçal is my guest today and her book, Mother of Invention, is such a witty, enlightening and important read. She weaves together the past and the present, illuminating the consequences of excluding women historically and showing us how we continue to make the same mistakes today. She also makes the argument that women's ingenuity and intelligence are the very things that can save us during this time of crisis we find ourselves in.

Katrine Marçal is a best-selling author on women and innovation. Her first book Who Cooked Adam Smith's Dinner? has been translated into more than 20 languages. Margaret Atwood called it " a smart, funny and readable book on women, economics, and money." It was named one of the Guardian's books of the year in 2015. BBC also named Katrine one of its 100 women in 2015. In her role as a financial journalist, she has interviewed many of the world's leading economic thinkers. Some of her interviews have been viewed more than a million times on YouTube. She was also one of only a handful of European journalists to get an exclusive interview with Michelle Obama before the publication of her memoir Becoming in 20 18.

She has given keynotes at institutions, such as Oxford University Business and Economics Program, London School of Economics and The Royal School of Technology in Stockholm. And she has delivered two excellent TEDx talks.

She also has a phenomenal newsletter called the Wealth of Women that is a short, funny, and feminist take on business, innovation and economics that comes out weekly and I would recommend everyone subscribe to.

Final thing. The three quotes you will hear read during the interview are taken directly from the book, The Mother of Invention.

As Katrine puts it in her book, "There is nothing wrong with men, but there is something wrong with a system that shuts women out".

She brilliantly exposes that system and shows us how women hold the key to our future. So please do share the interview if you want to help bring women back into this important narrative and save the world, essentially. But for now, sit back and enjoy my conversation with Katrine Marçal.

[00:04:29] Section: Episode interview

[00:04:30] Anna: Katrine Marçal, hello, welcome. Thanks so much for being here.

[00:04:34] Katrine: Thank you. Thank you for inviting me.

[00:04:37] Anna: I'm very excited about this conversation. But I actually wanted to start off with a question about your first book, which came out in 2012 called Who Cooked Adam Smith's Dinner? Because I think that question and everything that it represents really sets the framework for understanding traditional economic theory and what's missing from it, or rather who is missing from it. So can you lay out the premise of your argument for that book for us? How did Adam Smith get his dinner and why is this an economic importance?

[00:05:13] Katrine: Yeah, I'd love to. I mean, so it's a book about how women were left out of economics and why that's a huge problem. So Adam Smith is known as the founding father of economics and in 1776, he asked what became sort of the founding question of economics in this big book called The Wealth of Nations. And the question that he asks is how do you get your dinner? And that's actually a really good economic question. You know, we take it for granted more or less nowadays that we can go to the store and there will be things to buy there and things will work. And Adam Smith was interested in sort of why does it normally work? What are the forces that sort of keep these things happening? Cause lots of complex economic processes actually do have to take place just for a loaf of bread to be in the store when we need it. And his very famous answer to this founding question of economics, how do you get your dinner, was " it's not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker that you get your dinner. It's from them serving their own self interest."

So you know we go to our jobs, we go out and do what we do in the economy every day. Not because we love it, but because we want to, you know, make money, turn a profit. And economists that came after Adam Smith made a very big deal out of this. You know, self-interest was the answer to the founding question of economics and economics has even been called, you know, the science of self interest. What I do in my book Who Cooked Adam Smith's Dinner? is go back to this founding question of economics. How do you get your dinner? And I look at Adam Smith's life and the founding father of economics, he lived most of his life with his mother, Margaret Douglas, who looked after the household for him so that he can write profound books in economic theory. And she clearly had a lot to do with how he got his dinner. And he forgot about that. And in doing so, economics actually forgot about the often unpaid care and household work that women are still expected to do in the economy.

And they also got this bit about self-interest a bit wrong because if you actually acknowledge the contribution of Adam Smith's mother, you can't say that economics is just about self-interest because she didn't look after her son just out of self-interest. She probably did it out to love and care and sense of obligation, all of these other reasons for why we do what we do that economists tend to ignore. And that's something that we need to correct. I think that's the basic argument of the book, would you say?

[00:08:10] Anna: Yeah. Yeah. I think looking back at the history like that, it's so helpful for understanding where we are today and all of these current conversations happening around unpaid labor. And you know, how Adam Smith's mom would still not be counted today or seen by economic standards. So, you know, you wrote this 10 years ago, what do you see for how much progress has been made since you put this argument out into the world? And do you think it's still is as relevant now as it was then?

[00:08:39] Katrine: I do. I mean, it's been very interesting. I mean, I wrote it when I still lived in Sweden and I could never imagine that it would be translated into 20 plus languages and Margaret Atwood would read it and all the other amazing things that has happened. But I do think what's really interesting to me is that I think when I wrote it, it was quite controversial.

I remember when it came out in the UK where I now live and I gave a lecture at the London School of Economics on it, and I had people in the audience shouting at me really angry. And that was in 2015. And I do not think that would happen today because just as you mentioned, the conversation around unpaid labor and the care work of primarily women and the underpaid nature of many of these jobs, it has progressed a lot, I think.

[00:09:33] Anna: That's great. I'm glad to hear it though, let's not judge our progress just on if we get yelled at by men from the audience...

[00:09:39] Katrine: Oh, well, that's, that's a good, that's a good point, actually.

[00:09:43] Anna: ...a start though. So your new book, Mother of Invention is another macro view of the economy that looks at how inventions and innovative ideas are ignored being that they exist in an economy that was built for men as we've just discussed. But you don't just talk about how ideas are ignored, there's also that in this time of crisis, women's ingenuity and intelligence are the very things that can save us. So as kind of depressing as some of the messages can be, there's a very hopeful message about the future. So I'm really excited to talk to you about that.

Let's get into it. The overarching theme for the book was the fact that our economy and our world is shaped by gender. So to read a sentence from your book, you write " Virtually every aspect of our existence from the cars we drive and the luggage we carry, to the defining inventions of our past and the ideas that shape our future is affected by our deeply held beliefs about the role of men and women within society."

So can you elaborate on this idea more for us? How exactly do you see gender shaping our world and in turn the economy?

[00:10:56] Katrine: Oh, yeah. First, let me just thank you for saying it's a hopeful book because that's what I think as well. And then a lot of the reader feedback I've gotten is I liked the book, but it was so depressing and that's really not what I wanted. So I'm glad you read it the way I thought I was writing it.

Yes. Okay. Gender. So the book is largely about, you know, innovation and technology, and I think we tend to see, you know, the forces of technology as these neutral forces, that are just sort of coming along and moving everything around. And all we can do is sort of adapt or predict them, you know, how many robots are coming? What are they going to do to the labor market? What does this new technology mean? And that is not how it works because you know, we are humans and we are the ones funding these machines, building them, inventing them, scaling these businesses. And we come into all of these things that then become innovation, very, very shaped by all of our biases.

And you know, this book is about gender and how ideas about men and women and you know, what men and women should do and what gender is, has actually often held back technological progress and innovation and is still doing it. So it's a way of showing that these, these are not mutual forces there, you know, we do this and we can do it differently.

[00:12:34] Anna: Absolutely. You know, that's actually kind of the premise for this podcast is that we essentially divided the whole world up into two groups and then went on excluding one from fully participating and that reality has shaped all of our institutions and every aspect of our lives, but we just don't usually see it because that's how it always is.

So the purpose of this podcast is to kind of look at those different components of our world through a woman's perspective in order to identify how it's been shaped, without her consideration, how it's been shaped by gender and to add her back into the story. So I think that's, you know exactly how your book came across as like you say, looking at the forces, the people behind it, it's not just these invisible things that have created the economy. There are people doing it. And your book really paints a picture of how we ended up in a world where only 3% of venture capital money goes to women. Some of the lowest paid jobs we have are those that take care of children and the elderly and the sick, and nearly 70% of the world's poorest are women.

So excited to dive into that in more detail with you and better understand how gender has shaped the economy we have today, but first, why should we care? As you noted in your book, and as we've seen with Adam Smith economists have not always been known to consider gender. So what's your pitch, if you will, for why gender needs to be brought into our economic conversations and more importantly, our policies?

[00:14:05] Katrine: Well, I mean, firstly, if you're an economist and you want to have an accurate view of how the economy works. I mean, gender is for example, probably the primary thing that sort of divides our labor markets. You need to look at these things. Talking about my first book, if you look at just something like women's unpaid contribution to healthcare systems in the world, that's, you know, we're talking about 2.5 or something percent of global GDP. If you sort of add that contribution together, it's huge. The figure is massive. And obviously., You know, if you do anything, any sort of policy to the economy, for example, there is a big pandemic and you shut down huge parts of the formal economy, that's going to have an effect, you know, if you shut schools and childcare centers, and suddenly kids have to be looked after at home and people are still expected to do paid work.

You're going to have an effect which, we've had, which has been sort of the great resignation of women from the labor market, particularly in the U S. And you can not explain that unless you look at gender as a factor. And then if you're talking about something like innovation that my book Mother of Invention is about, it's all about releasing that potential.

I mean, we all agree that we need innovation and new ideas to solve the big challenges we have. And we are basically innovating with at least one hand tied behind our backs, because, you know, as you mentioned, we are not funding and finding and scaling women's ideas for no other reason than that we are blinded by gender and, you know, we can do better and we should do better.

[00:15:50] Anna: Absolutely. It's pretty maddening to think about how much innovation we're losing out on when you look at the statistics of funding and just consider women's difficulty in accessing and bringing their ideas to market.

So looking into your book a bit more now than so they say history repeats itself, and one of the best ways we can learn is to study our past and in particular, the mistakes of our past. And you open the book with a few great examples of how innovation was held back because of society's beliefs about gender and the roles they play. One being the rolling suitcase, something most of us couldn't imagine living without though it turns out we almost had to thanks to our stubborn views of masculinity. Can you share that story with us? Why did we almost have to forever carry our suitcases?

[00:16:42] Katrine: You know we did for a very long time, which is, is one of the sort of classic mysteries of innovation that, I mean, Nobel Prize winners in economics and innovation thinkers from sort of more of a management perspective and lots of other people have pondered, because it's a fact that we invented the wheel of 5,000 years ago, but we didn't put wheels on suitcases until the 1970s. So we actually managed to put two men on the moon before somebody came up with this idea, you know, we have this 5,000 year old technology of the wheel, Let's attach it to the suitcase and wa you know, that's great. And how could we have been so stupid? Um, that's something a lot of people have thought about, what people have not done before, before me, before this book is actually, I think, really look into this story, because as soon as you do, you pretty immediately realize that there's a huge gender component here. And, you know, I didn't find that because I'm particularly clever or anything. I stumbled upon it because it is there and nobody had really looked at it like that because I think we're not used to thinking about gender and innovation like that.

But you look into this a bit and you find that actually there were suitcases with wheels before the 1970s. Most of them, however, were these niche products for women that never took off and nobody really saw the potential in. And why was that? Well, a lot of that had to do with the fact that there was this idea that no man would ever roll a suitcase. It was simply ridiculous that a man would roll a suitcase because masculinity is one of these things, it can never just exist, it always has to be proven, right? And one of the ways that men have to prove their masculinity is through sort of carrying heavy suitcases. And this idea really made the luggage industry and almost everybody else completely dismiss this idea. No male consumer will buy this type of product.

Women might, but they're too small of a market because hey, women don't travel alone. Right? If a woman travels, the assumption was she will do it with a man who will then have to carry her bag in order to prove that he's a real man. So no, there's no market. Thank you. And this was then obviously proven wrong.

And the rolling suitcase was initially marketed to this sort of new emerging idea of a female business woman that, you know, came in in large parts of the world and the 1970s. And then, there was this big shift when women started traveling more and also masculinity or ideas about masculinity changed, and, you know, we were finally able to accept this, this idea that, you know, you can still be a man and roll a suitcase. And this product took off and obviously completely disrupted the whole global luggage industry. And today we've forgotten about this really gendered resistance to it, but it was there and it wasn't long ago.

[00:19:50] Anna: No, it was not long ago at all. And in this context, we can better understand past mistake number two that you mentioned, which blew my mind a little bit, cause I had no idea that this happened. So when the first car came about, there wasn't just one market for it, but two and as we'll get into given our current climate emergency, it is pretty hard not to think about what could have been if things had turned out differently. So could you tell us about that past mistake as well and how that kind of ties into this same theme?

[00:20:23] Katrine: Yeah. I mean, because you can say, and, and, and some people do to me, well, you know, yeah rolling suitcases, whatever. It's, it's a funny story, but it's not that crucial. But, gender actually has played a part in, you know, many, many other things when it comes to innovation. And the one you're talking about is I think quite an interesting one, which is because it has to do with electric vehicles.

So electric cars are all the rage now, obviously. But they are quite old. You know, we had electric cars already at the dawn of the automobile era. There were, petrol driven cars and there were electric cars and the were cars driven using different forms of steam technology. And all of these types of technology where it competing against each other as is the case and, and should be the case.

What's interesting and what I note in the book is that electric cars pretty soon began to be marketed quite heavily towards women. And the ads from that period are just, just amazing. The sort of women in long skirts and amazing hats getting into these beautiful electric cars. For example, in 1909, when Henry Ford launched the T Ford, uh, which was supposed to be, you know, a car for everyone, his own wife, Clara Ford went out and bought an electric car because that was the sort of women's vehicle.

And there was this idea that a car that was a bit slower, but very good for sort of urban areas, a car that was safer and cleaner, and more comfortable, which the electric was, must be feminine. Which is very random, really but, but that was the case. And what pretty soon happened was that the feminine associations between electric car technology and women, and femininity led to male consumers not wanting it, because this was like, this wasn't technology, this wasn't a real car. It was a drawing room on wheels, something for the ladies and many men dismissed it. And this actually contributed, it wasn't the main reason to why we decided that let's build a whole world for petrol driven technology. Uh, but it was, it was there and it was part of it and historians often talk about, you know, other cultural reasons for the electric cars, disappearing and I say in the book that we should call those other cultural reasons for what they are, which is a sexism.

[00:22:56] Anna: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I didn't know that a hundred years ago we had electric fire engines, electric taxis, electric buses in most of the world's major cities as you pointed out, and then they disappeared , and even if that wasn't the main factor, it is just hard not to imagine things turning out differently or what could have been if masculinity wasn't threatened by comfortable vehicles and anything relating to the feminine.

[00:23:26] Katrine: Yeah.

[00:23:27] Book excerpt: “...as it happens, the world is full of people who would rather die than let go of certain notions of masculinity. Doctrines like ‘real men don’t eat vegetables’, ‘real men don’t get check-ups for minor things’ and ‘real men don’t have sex with condoms’ literally kill very real men of flesh and blood every single day. Our society’s ideas on masculinity are some of the most unyielding ideas we have, and our culture often values the preservation of certain concepts of masculinity over death itself. In this context, such ideas are certainly powerful enough to hold back technological innovation for five millennia or so. But we just aren’t used to thinking about gender in relation to innovation in this way.”

[00:24:15] Anna: So as you point out throughout the book, and as we've just seen the economic consequences of what we choose to label as masculine and feminine can be enormous. And that's both at a societal level, but also for individuals or at least individual women. And, um, it seems one of the most significant ways that we do this is how we define technology.

What is, and isn't considered technology and what is, and isn't considered a technical skill. You argue that the feminine label is equated to the low paid as a direct result of our refusal to view what a woman does as technical. Can you take us through this argument and provide some examples of how we've seen this play out over the centuries or really over the millennia?

[00:25:00] Katrine: Yeah. So I guess this is kind of the theoretical concept of the book. So let's, let's take my mother as an example. So, I'm born in the early 1980s in Sweden. And when my mother had me, I was her first child. She decided that she wanted, you know, more sort of stable career, something that was give her, give her a bit more flexibility, but would also sort of, you know, decent job.

So she decided to retrain, and she went to university and she did something which was still quite natural for somebody of her background to do is she went and she studied computer science. And she was somebody who had worked at an art gallery and then with the administration of library catalogs in Sweden went to study of computer science, became a computer programmer.

So in that sense, I grew up in the tech industry before it was called that, and it was still pretty female dominated back then, particularly programming. I remember how most of my mother's managers, when I was little, were still, you know, women with big curly hair that brought cakes. That's the image of tech that I grew up with, then it all changed.

And obviously when my mother retired a few years back, the industry that she was retiring from was hyper-masculine and the female history of computer programming was largely forgotten. I mean, the first programmers in the world were women, women invented software. And within sort of my lifetime, I'm, you know, I'm going to be 39 this year, we've forgotten all of that. And that's one example of this point that I'm trying to make throughout the book Mother of Invention is that, you know, when women invent or do something, we just refuse to see it as technology. Um, you know, when women were doing programming, it wasn't seen as very technical when they were inventing software that wasn't seen as technology.

And that happens again and again, throughout the history of innovation. When women do something or a good at something, we see it as some kind of natural female ability, which doesn't require many skills. And then the economic logic dictates that, well, if it's a natural female ability to do anything from doing things within the dairy industry or programming a computer, then you know, why should we pay them very well?

And then the men come in and they take over some of these industries and suddenly it's a skill, suddenly it's tech, suddenly its technology suddenly it's high status and suddenly the women are just gone. And it's, yeah, that's largely how it is unfortunately.

[00:27:45] Anna: And you talk about how that wasn't the first time, you know, from antiquity until the end of the 19th century secretaries was a high status role for men. And do you also compare midwifery to doctors and how the tools were literally taken out of their hands because women weren't supposed to be able to use metal instruments was a actual law and rule, so we see that kind of trickle down to today where you have midwives doing essentially the same thing but getting paid a lot less and the status of their job being quite different than what a doctor is. And you talk about art and the types of technology that men use in their art that they produce compared to women. And, it just goes on and on and on. And if I could just read one more excerpt from your book that I think summarizes this quite well.

You said, "One of the greatest consequences of the patriarchy is that it makes us forget who we really are. If we instead took those aspects of the human experience that we have coded as female and recognize them as universal, we would change our entire definition of what it means to be human. The crux of the problem has always been that the human has been equated to male. Woman is some sort of supplement made as we know from a single rib." I thought that that was very powerful.

And then another area to look at and understand our current situation is funding or lack thereof. And based on everything we've discussed so far, the fact that anything that's gets labeled as feminine from actual skills to physical materials decreases in value, it will be no surprise that there are massive gaps in funding between women and men.

I want to lay out some stats from your book to make sure we're all on the same page about the gravity of the situation. And then I want to talk about how we got here as to understand that better. So as it stands, 3% of all VC funds in the world go to women. In the UK, it's less than 1%, in Sweden where you're from and as a country known for doing a lot more it's just over 1%, in the US it's less than 3%, even though nearly 40% of businesses in the U S are owned by women. It's currently estimated that 80% of all female owned businesses have unmet needs for credit. At the current rate, it will take 25 years for women to get their hands on just 10% of the money. And to top it all off there isn't a single country on the planet in which women collectively don't have less money and less economic opportunity than men and all of this, despite the fact that businesses started by women generally turn a profit faster than those started by men, which is just tragically ironic.

So I think we can all start to understand the bigger picture, how this could possibly be. But of course there's a lot more to the story than just labeling skills as feminine and then refusing to fund them. So could you help us understand how we got here? Maybe starting with what venture capital is for anyone who might not know and where it comes from? I think that was a really interesting anecdote from the book. And then, yeah, how has that given rise to the massive gap we see today?

[00:31:03] Katrine: Yeah. I mean, so firstly, I just think it's important to sort of understand what, what this is. Cause you know, obviously there's lots of ways to get funding for an idea or business and venture capitalist is just one of them, but talking about venture capital, it is something that is increasing in importance and in a world where particularly the big sort of tech companies have this massive sort of global political influence, enormous economic influence over our world.

And that sector has largely been fueled by venture capital. And then the fact that men, the statistics you've read out, almost have a complete monopoly on this type of funding is actually very serious, because what this means is that the business models that you know are going to define things in the future, the healthcare, the AI, the tech, that's going to be hugely influential and rule our lives largely in the future is created almost exclusively by men.

And this is why this type of funding I think is relevant to discuss, because it's easy to say, oh, you know, all of those gender things you talk about, it's just in the past, it's, you know, we don't have these problems anymore, but we do have these problems anymore. And particularly we, we have these problems in the future because of the funding decisions we make today.

So that's, that's why it's relevant. Then what I talk about in the book is that it's not just an issue of woman comes in and pitches business idea, and then man comes in and pitches the same business idea, and man gets the money and woman doesn't get the money, that happens too. But, um, and it happens quite a lot, but, the main reason I argue in the book is the structure of venture capital. In the book I tell the story of, of how it's, you know, it came from the whaling industry and it was a tool to finance these high risk, potentially high return whaling expeditions. The way it's structured means that it's particularly badly suited to see and fund and scale the type of business ideas that women tend to have. Because as you also say in a women's businesses tend to be, for example, profitable earlier, which is actually a bad thing if you want to go for venture capital. A venture capital is looking for a type of idea that can either fail completely or become the next Facebook. And sort of women tend to be creating things that don't really fit that model. And therefore we have this huge funding gap and we basically need to fix this problem using financial innovation. We need other type of funding logics that can better capture the innovative potential of women.

[00:33:58] Anna: And we'll get into some solutions towards the end. But yeah, I think again, just considering how many ideas we've lost out of, you know, thinking about how long it's taken to innovate the breast pump, for example, or we're seeing now all of these innovations around menstrual hygiene technologies and technologies that address sexual harassment and everything else. And this is still given the lack of funding, you know, so what would it be if we were actually on a level playing field?

[00:34:27] Katrine: Yeah, particularly since, you know, women are, have, have quite a lot of consumer power in today's economy. So women are thought to influence around 80% of all consumer decisions. That's huge. Um, so, you know, there should be, I mean, the fact that there is not more funding into particularly consumer products for women is actually a pretty clear cut market failure I think. You know, I think investors are leaving money on the table, which they normally say they don't like to do. But you know, I think Mother of Invention shows again and again, that actually often when we are, we have to choose between upholding certain ideas of masculinity and femininity or making money, surprisingly often we actually choose upholding gender roles, um, before making money. And that's, that's strange.

[00:35:17] Book excerpt: “Who will want to invent a self-cleaning house when we live in a world in which women earn their living by cleaning for $8 per hour? Who will want technology to solve problems that remain invisible, since they are currently being taken care of by women for free? What we value and don’t value in society affects the type of technology that tomorrow will bring. There is nothing strange about this; we simply need to be aware of it. Then we will realise that we always have a choice, and that the best way to predict the future, is to create it.”

[00:35:58] Anna: All right. So as we've mentioned, easy to look back and laugh at the ridiculousness of the fact that man's masculinity was threatened by comfortable cars and tiny wheels, but the second half of your book really illuminates the fact that we are making these same mistakes today and mistakes that will probably be laughed at, by future generations in the exact same way. But they're just a lot harder for us to see now. So we've talked about funding and then you also talk about the pandemic about robots and about the climate emergency. So starting with perhaps kind of the pandemic and robots, we have this narrative, I loved how you kind've took this narrative apart. We have this narrative that robots are going to descend in on us and steal all of our jobs, you know, any day.

And obviously there are jobs that are being replaced by new technologies, but, you know, you point out if this happens, it's not a consequence of technology. It's a consequence of the choices that we make along the way. It's not because the robots are coming, it's because we are creating them and organizing society accordingly. And as you do in your fantastic writing, looking at the past and tying that into the present, you pulled out the example of 300 years ago, the first machine age, and compare that to where we are with the current movement. So can you tell us a little bit about, how we kind of have been here before, um, a few centuries ago and yeah, what can that tell us about our current moment?

[00:37:30] Katrine: Yeah. I mean, so all the clever people are talking about that we are in a second machine age right now, so that new technology is coming and it's disrupting our lives. And the consequences of that, you know, will be huge. And we can't see the full extent of it because we're in the middle of it. And you know, Okay yeah. That's, that's probably true. But if there was a second machine age there, that means there was the first machine age. And when we talk about the first machine age, that tends to mean the industrial revolution that went on in the 18 hundreds centered in, largely in, in Northern England. So I look into that in the book, because there was a famous man called Friedrich Engels who then went on to found communism with his friend Karl Marx.

But before that, he was, he was a journalist going up to Northern England, looking at the consequences of new technology, the new machines they were coming in, you know, huge factories being built, these large areas of the country being disrupted. And he described in a very famous book that radicalized a lot of people at the time, just the consequences, this new technology, that were making a few people, very rich had for communities and people in terms of poverty, jobs being lost, environmental destruction and so on, you know, what were the consequences of these new machines? And it's interesting, that in this book, he actually talks a lot about gendered effects of new technology. Cause he is describing a situation in the first machine age, back in the 1800s where new machines were coming in and they were not making everybody unemployed. They were making a certain group of men unemployed because with those types of new machines, suddenly physical strength didn't matter as much on the factory floors. So the owners of the factories, they got rid of many male workers and they hired women and children to do the jobs instead because they were cheaper.

You know, the wages were lower. And this led to a situation with sort of many men being unemployed and the wife having to be the breadwinner and Friedrich Engels, you know, who then went on to found communism, describes with outrage, this situation sort of how new machines are deemed masculine. What's it called? De masculine...

[00:39:59] Anna: oh, emasculating.

[00:40:02] Katrine: Sorry. Um, um, Swede trying to speak English, uh, emasculating men, and how we need to do something about this. And I found that very interesting, but in that the first machine age and the consequences of that new technology were actually discussed at the time connected to gender in this way by probably the most famous guy who wrote about it.

And that ties back to the second machine age, which they say we're in now, because if you look at many of the studies coming out where economists are doing their best, trying to predict, you know, which jobs are the robots going to take and which ones are, they're not going to take, you can actually see a similar thing that many of the jobs that are highly likely to be automated are male jobs.

And a lot of the things that women actually have been specializing in, in the economy, care working with, you know, other humans, these types of jobs, cleaning, you know, are actually much harder to automate and that could mean, I mean, obviously we don't know, we're still trying to guess the future here, although using data is that, this wave of technology will also have very gendered consequences on the labor market could make a lot of men unemployed, a lot of the traditionally female jobs, you know, there would still be demand for human workers in those sectors of the economy. What will that mean? That's an interesting question I think.

[00:41:36] Anna: That's a very interesting question. And you know, you talk about your mom and what happened to that industry and is it going to be a future where the care industry is dominated by men and held up as this wonderful sector, high-paying sector for everybody to get into? Um, and the question you pose in your book, which I believe was just kind of a thought provoking question was "Will the economic problems of the future be less about girls not having been encouraged to code as much as boys not having been encouraged to care?"

So can you paint a picture then of what is possible if we do it right this time? You know, what should we be thinking about to make sure that we're not repeating the same mistakes that happened back then? Because it was obviously, it was a, you write in your book about how it was a very turbulent time, this transition. And there was a lot of, of human suffering that went along with this transition. So yeah, what can we do better?

[00:42:33] Katrine: I mean, I think it's that sort of basic acknowledgement that, you know, technology is an innovation is not this neutral force. And because we are the ones creating these machines, we also have to create political institutions and political innovation and societal innovation that can handle these types of transitions.

So it's, it's all about that and it's that we can, and we should steer these things. And I think there is a big opportunity in this technological shift that, if actually new technology can come in and do a lot of sort of repetitive work for us. And that would actually enable more and more humans to be able to specialize in, you know, things that have to do with other humans and relationships and being human and art.

And, um, all of these other things that I think most people would say, are more meaningful to both men and women really. So in that sense, there's an real opportunity to rearrange the economy so that more people can find much more meaningful roles. And in that sense, the robots will then have helped us become more human in a way. um, and that be a wonderful, wonderful thing. And that's the kind of, uh, I think a political vision that we'll need to, to guide that type of institution building and innovation around the human consequences of this, of this transition. And I obviously think that, you know, having a gender perspective and a feminist perspective in there would be very important.

[00:44:17] Anna: Yeah, fascinating.

[00:44:18] Book excerpt: “’Mother Nature’ we say, and yes, it does have a nice ring to it. But what is a ‘mother’, really, in a patriarchal society? She is someone who can be expected to give her all without ever complaining, someone who has no needs of her own and lives entirely for others. Mummy dearest cleans up any traces of pollution by simply changing our nappies, and every morning when we wake up the kitchen has been cleaned and the floors mopped and we can go on flinging our toys around without a single thought to how much time it might take to pick them up. Our idea of the mother is, in essence, an idea of a woman who looks after us and loves us regardless of how we behave. This is pretty much the last things our planet needs to be compared to right now.”

[00:45:16] Anna: And then getting onto the climate emergency, which is perhaps the most pressing way we continue to make the same mistakes of the past. So you write about the increasing overlap between nationalism, anti-feminism, racism and a resistance to everything that the climate movement represents.

And you admit that this may seem deeply illogical until we consider, the idea of nature as a woman. Saying that climate change is not only the greatest innovation problem of our day, but it's a problem tangled up with our ideas about gender. So can you elaborate on that? How do we currently view nature and what does gender have to do with the current emergency we find ourselves in?

[00:46:00] Katrine: Yeah. So, I mean, so what I do, I basically kind of throw in this little problem of the climate emergency in the last chapter. Um, but hey, okay. Um, it needs to be there. And I thought that is where the book needs to end. And particularly because the whole book is about these things that we code as feminine, whether that's wheels on suitcases or electric cars, or computer programming before it became male, and saying that the things that we code is feminine are not taken seriously and are seen as inferior to things that we decide for different reasons to see as masculine. And if you're doing a whole book with those types of examples, you cannot not acknowledge the fact that the biggest thing that we have coded as feminine in our culture is probably nature.

So, you know, mother earth, right? And this sort of concept of nature as this feminine force that then the masculine forces of technology should control and extract resources from, and the similarities there with sort of, you know, because often women are seen as this natural resource that we can just like keep extracting unpaid labor from and there will never be a consequence because there will always be, yeah, there will always be more. We do, we do tend to look at nature in a similar way. And I do think because so much of the discussion around the climate emergency is very gendered and very tied up in these ideas. You need to kind of start with this and with looking at why we see nature as, as feminine and what that means.

[00:47:42] Anna: Yeah. You say that the political parties and leaders who are currently doing the most to deny climate emergency today are almost always the very same ones that want to put women back in their place. So they're kind of inextricably linked. So again, to kind of put that back on you of what do you think it's going to take to change things? What kind of policies do we need to put in place and to kind of use your own question that you asked, do we need to invent or reform our way out of this?

[00:48:12] Katrine: Yeah, I mean, I do you really think, I mean, the climate emergency is one of these sort of throw everything at it, sort of throw everything at it in an intelligent way kind of problems. It's, it's a very, very complex problem. I mean, what I do talk about in this book, because it is a book about innovation and is that, you know, take my fellow Swede, Greta Thunberg her very famous question that she put to the UN " how dare you, how dare you not to do more to, to stop this sort of climate disaster."

And to be honest, you know, the answer to that question, how dare you has a lot to do with, you know, how you see innovation and technology, because the reason why many of the world's leaders in that room have dared not to do more is because they do think that we will invent technology at some point that will fix at least part of this problem for us, which means that, you know, how you view how much needs to be done here, and now has a lot to do with how you see, or how you look at the possibilities of, of technology and innovation.

And from there in the book, I go into this, um, um, I start talking about witches basically, um,

[00:49:32] Anna: I love this part.

[00:49:34] Katrine: So the American science journalist Chelsea Man, he has this distinction, between wizards and prophets when it comes to how you see innovation and, and technology. And he talks about how any discussion about almost any sort of environmental issue for decades has been this not very productive duel between wizards and prophets. So on one hand we have the wizards and that would be somebody like Elon Musk, for example. So somebody who really believes in the power of innovation and technology, you know, human beings, we've had to sort of deal with all of these problems in the past and we've always kind of invented ourselves out of them. So innovation and technology is clearly, the solution even to the climate emergency. That's what a wizard thinks. And on the other hand, we have the prophets and they say the opposite. They say that, you know, technology and innovation is how we messed everything up.

You know, that's where the pollution comes from. It comes from the machines. So how can more machines be the solution? No, we need to sort of live differently. We need behavioral change. We need sort of another vision of the good life. And technology can't be the solution. And then they kind of fight it out like this over every single environmental issue and we're not getting anywhere.

And there's a lot of frustration because most of us, I think, understand that it's both about new technology and behavioral change and they happen in, you know, what came first, suitcase with wheels or the behavioral change necessary for men to be able to roll them. It's all kind of tied up in each other.

How can't we sort of get past this, the wizard and the prophet. And that's when I start talking about witches as, as an archetype that has a different relationship to nature because both the wizard and the prophet, they do see nature as this thing that's not part of them and that they're not part of. It's sort of this feminine other. And we could have an innovation paradigm that was much more like the archetype of the witch. So she's different from the wizard in the way that he's up in his tower getting his knowledge from formal books and sort of his magic, his technology is something to sort of control the outside world. Well, the archetype of the witch she's still magic, but she's, you know, down in the forest, she's doing interesting things with herb's and, and ritual.

And she very much sees herself as part of nature and her magic comes from it, not to control it. And that's a different sort of innovation and technology archetype that I think we have dismissed largely because of this insistence of viewing nature as this other feminine thing that, that should be controlled and worked against. And, and I think we do need a different innovation and technology paradigm to sort of this climate emergency.

[00:52:39] Anna: That's fantastic. And when you read your book, all of this really comes full circle because you started out the chapter talking about the great European witch trials that killed up to a million people, mainly women that actually we look back on and we think was linked to climate change. There was a Little Ice Age starting in 1590, that kind of triggered these weather events that people needed someone to blame for their crops failing, for the floods, for everything that happened linked to this climate crisis, so they blamed the witches and here we are today. And with your analogy, moving forward into the future, looking to the wisdom of witches to get us out of it, full circle.

[00:53:20] Overdub: “And now for: “men are losers too”... in gender inequality of course. These are not "women's" issues, these are everyone's issues, because as long as women are held back from their full potential, so are we all.”

[00:53:35] Anna: Moving on here, I want to talk about men for

[00:53:37] Katrine: Oh, yeah. Favorite topic.

[00:53:41] Anna: There's a recurrent segment on this podcast that looks at all the ways gender inequality negatively impacts men, so I would love to know how do you think men are negatively impacted by the current economy and innovation and what do they stand to gain in a more equal world?

[00:53:58] Katrine: Oh, I love that I think we should talk a lot more about that because I think sometimes we get the impression that, you know, it's all about, women taking money and power from men and they get like, oh, the right to cry in public in exchange. And, you know, sometimes, but it doesn't, you know, for those of us who don't like crying in public because we're Northern European and a bit sort of, you know, um, that doesn't sound like a very great deal, but, um, I do think you men have everything to gain from this.

And I think, I mean, firstly, on a, quite sort of deep and existential level and you alluded to this earlier, it's, you know, it's, it's a mistake, the way we take the human experience and say, these parts of the human experience are feminine and these parts are masculine and never should they meet. Because we are denying people, both men and women, the experience of the full extent of what it means to be human, which consists of, strength and autonomy and those things that we tend to see as masculine, but also of vulnerability and emotion and that type of depth.

And it's all of those things. And we are denying both men and women that experience in patriarchy, which is why we need to get rid of it as a system. So that's sort of on an existential level and, but I also think. You know, it's, it's, you know, connection with, children and loved ones and time and, and all these things, you know, men have so much to gain from this type of shift and meaning, and, and also, you know, looking at it strictly from like an innovation economy perspective, we are ignoring a lot of good ideas, we are leaving money on the table and often for very kind of, you know, if you pinpoint them quite random reasons, you know, this is male, this is female, therefore this idea can't be. So I think there's so much potential and you know, we are innovating with at least one hand tied behind our backs and, what could happen if we released, if we cut that rope, I mean anything, and that's quite exciting to think about.

[00:56:09] Anna: I love that it's very exciting to think about. And another benefit is they can continue living on this planet when we

[00:56:16] Katrine: Yeah. That one, I forgot about that one. You will actually, you will actually be able to survive. Um, yeah, that's a great one. I'll note of that one.

[00:56:29] Anna: All right. So you said that you think women holds the key to our future. And there was one question on the cover of your book that I would like to pose to you relating to that point. What do you think the world would be like if we listen to women?

[00:56:44] Katrine: I think it would be much more, uh, exciting. I think it would make a lot more sense. I think, I think because again, it's, it's about this balance and, you know, shutting at least half of humanity out of that decision-making process and not giving them that power, it just creates this really unbalanced system that I think we're all suffering from. So I think it would be very, um, exciting is the word I'm going to go for.

[00:57:16] Anna: If listeners take one thing away from this conversation with you today, what would you want it to be?

[00:57:22] Katrine: I think it would be that when you look back at the history of innovation, the way we tell it, it looks as if everything important has ever, ever has been invented by men. And the big takeaway is that that's, that's not true. And the reason that's not true is that when women have invented things, we don't see them as technology in the same way.

And therefore they don't get to be a part of this grand narrative of innovation. We talk about the Bronze Age and the Iron Age and the Stone Age, but why don't we talk about, you know, for example, the ceramic age or the flax age, or the string age, you know, all of these things, ceramics, all the technology around weaving or string as an invention, those are technological inventions, you know, we think were done by women. But we don't see them as such. And that creates this narrative of innovation that I think effects women today. Where when you studying the history of innovation, you are studying your own absence, which doesn't exactly encourage you to sort of go out and go for that funding for your new idea.

And therefore, I think it is very, you know, not just inaccurate, but very destructive. So I do think this, the takeaway that technology historically has basically been defined as whatever men do, that would be what I would wish for people to takeaway.

[00:58:46] Overdub: And now for: “Your Story”, the part where you are invited to reflect on this story as it relates to your own life - think about it, write about it, talk about it, and if you wish, share with the community. Whether or not you are listening in real-time, if you send in your thoughts, experiences, questions, and recommendations, they may be included in a future listener-led episode. Check out the link in the show notes, or revisit the Your Story episode, to learn more. Remember, no matter your story, you are not alone in your experience, and there is power in our collective realisation of this.

[00:59:28] Anna: You write and have talked about the importance of bringing women into the narrative. That if we do the entire narrative that we hold about the economy, about the world becomes something else and a new way emerges. And that's exactly the type of space that I would like to provide in this last section of the podcast, where we invite listeners to share their own stories.

So as listeners come away from this hour with you, are there any questions that you want to put forth to them as they consider their own narrative? What can they pay attention to? Are there ways they can reflect on their own experiences or anything else you'd like to ask?

[01:00:05] Katrine: Yeah. I mean, for me, one of the things that I thought about a lot when I was working on this book was that when you, as a woman, when you're good at something, we tend to see it as not as a skill, but as like a natural female ability, which then makes us kind of, you know, take it for granted in an economic sense.

And that's something, you know, for me that was very useful to just think about even in my own life, when has that happened to me? And when do I even do that to myself? Because when you look at that from the macro level, which I do in the book, you know, what's the consequence of us looking at the things women do in the economy as natural abilities and not as skills, hard acquired skills that should be paid well, the macro implications of that financially are massive, but when it happens to you in your own life, you tend to maybe not take it in a see it or take it that seriously. So that was something that I personally thought about a lot and also something that readers who've sort of written to me or, come up to me after I've been giving talks have said, so maybe that's something to think about it.

[01:01:13] Overdub: And now for: the “feminism gets a bad wrap because the narrative has been just a bit one-sided" corner.

[01:01:20] Anna: Great. All right now for some rapid fire questions to wrap up, these are the questions that I ask every guest at the end. So Katrine, what does feminism mean to you?

[01:01:32] Katrine: I think it's the radical notion that you know, women are are, are humans.

[01:01:39] Anna: Radical notion. Uh, what is one of your earliest memories of gender, a time when you realize the world didn't treat girls and boys the same?

[01:01:48] Katrine: So I had, I had, I didn't have very much hair growth as a child. Um, it took me some time to grow hair and when I was at nursery, because I had very little hair, the other girls, this is a sad story, told that I was a boy and that I was not allowed to play My Little Pony with them because there were no male ponies in My Little Pony, which is factually untrue. Um, and also it was just mean, um, yeah, that that's an early memory of gender and the need to conform to things and yeah.

[01:02:23] Anna: Oh, yeah. In a very sad one. Well your hair is beautiful for what it's worth. What is the story of woman to you?

[01:02:33] Katrine: Why do you take like the most difficult questions put them as rapid fire questions? That is not fair!

[01:02:42] Anna: Yeah. To get you the best possible concise...

[01:02:45] Katrine: I think the story, the story of women is like the thing that will, the great untold thing that will save us. I do think that all the things that we have, almost all the things that we have categorized for different reasons as feminine and therefore excluded from things like, for example, economics bringing them back in, bringing that story back in, is where the solution to almost all of our problems will come from.

[01:03:13] Anna: Yes. See, beautiful response. These are probably a bit more rapid fire, like you're thinking, what are you reading right now?

[01:03:21] Katrine: I am a rereading Tinker Tailor Spy, is that what it's called, by John le Carre, the British spy author.

[01:03:29] Anna: Oh, very nice. Any, um, top books that you would recommend?

[01:03:34] Katrine: Um, anything by Ursula Le Guin because I like science fiction and she is the best science fiction writer. And, also anyone who's interested in gender and hasn't read, The Left Hand of Darkness, uh, needs to read it and also because it has a great descriptions of snow. Um, so that's, that's great feminist read, uh, I also recently read, Unwell Women by Elinor Cleghorn, think you've interviewed. Yeah. Which I thoroughly, recommend. And, uh, yeah, we'll start with those.

[01:04:06] Anna: Great, uh, who should I make sure to have on the podcast? And it's okay to be aspirational.

[01:04:15] Katrine: Um, uh, well, you know, get Margaret Atwood on, right?

[01:04:19] Anna: Yes. Oh, that'd be a dream. Hey, you kinda know her now right?

[01:04:23] Katrine: I don't know her, no she's tweeted about me once, so yeah we've very, very close friends.

[01:04:28] Anna: Uh, what are you working on now?

[01:04:31] Katrine: I'm working on a new book, called A Woman's Worth.

[01:04:35] Anna: Yeah. All right. More to come on that. Well, where can we find you so that we can find out when that book comes?

[01:04:42] Katrine: Yeah. So I have a website, which is katrinemarcal.com. And, there's hopefully updated information on there. Mainly I have a newsletter which is free that you can sign up for which I have a lot of fun writing. It comes out every week. It's called The Wealth of Women and it's like a short, hopefully, funny, um, enlightening take on, you know, economics, women, business, innovation, all the things I think about.

[01:05:10] Anna: Yes. I recommend this for everyone. She's a phenomenal writer, very enjoyable to read. I will put all this in the show notes as well, but excellent. Well, thank you so much for your time today, Katrine, it has been an absolute pleasure. Great to speak with you.

[01:05:26] Katrine: Thank you.

[01:05:27] Overdub: Thanks you for listening. The Story of Woman is a one-woman operation, with voiceovers done by Jenny Sudborough.

If you enjoyed this episode, there are a few small things you can do that make a big difference in helping other people find the podcast and allowing me to continue putting out new episodes! You can subscribe, leave a review, share with a friend, follow us on social, buy me coffee (not literally - this is the name of the platform to raise production funds - but hey, I’d grab a coffee as well), or head to the website and check out the bookstore filled with 100's of books like this one. If you purchase any book through the links on the website, you support this podcast - and local bookstores! Soooo feel free to do all your book shopping there! All of these options are in the show notes.

Anything you can do is appreciated and makes a big difference in elevating woman from the footnotes of history to the main narrative.

💌 Sharing is caring