[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Overdub: Hello, welcome to The Story of Woman, the podcast exploring what a man-made world looks like when we see it through her eyes. Woman's perspective is missing from our understanding of the world. This podcast is on a mission to change that. I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein Lau and each episode I'll be speaking with an author about the implications of her absence - how we got here, what still needs to be changed, and how telling her story will improve everyone's next chapter.

[00:00:34] Section: Episode level introduction

[00:00:35] Anna: Hello friends. Welcome. Welcome. Thank you for being here, as always. Today, we are continuing the conversation that we started last week. We are talking about abortion. These episodes don't need to be listened to in order, but if you haven't already, I would recommend listening to episode 13, where I discuss access to abortion in America or lack thereof.

That is what we explored in the previous episode. And in this one, we are talking about the morality of abortion. Something I personally think needs to be discussed a lot more on the pro-choice side of this conversation. Morals and religion, and the principles of right and wrong are applied the most by the anti-abortion community. But the reality is there is a very strong moral case for abortion as my guest gets into today. I will avoid a long tangent on this topic for this episode, as I did plenty of that in the last episode, episode 13, where I talk briefly about my background of being raised in a deeply antiabortion community, where morals were the number one thing discussed.

I mean, how could people kill babies? It doesn't get much more immoral than that! But of course that is not the full picture, not by a long shot. That is just a narrow and very distorted view of the story. But like I said, listen to my rant in the previous episode for more on that, I am going to move along here.

I'm recording this on May 20th 2022 with the Supreme court do to rule on a case that could overturn Roe V. Wade in June, Roe V. Wade being the thing that protects a pregnant woman's liberty to choose to have an abortion without excessive government restriction in America And their are draft decision was leaked to the world recently, so we pretty much all know how this is going to go down. There is likely to be a lot that has changed in the abortion landscape by the time this recording finds your ears. But whether you are listening on the day it's released or a year later, this conversation will still be relevant and abortion will almost certainly still be oppressing.

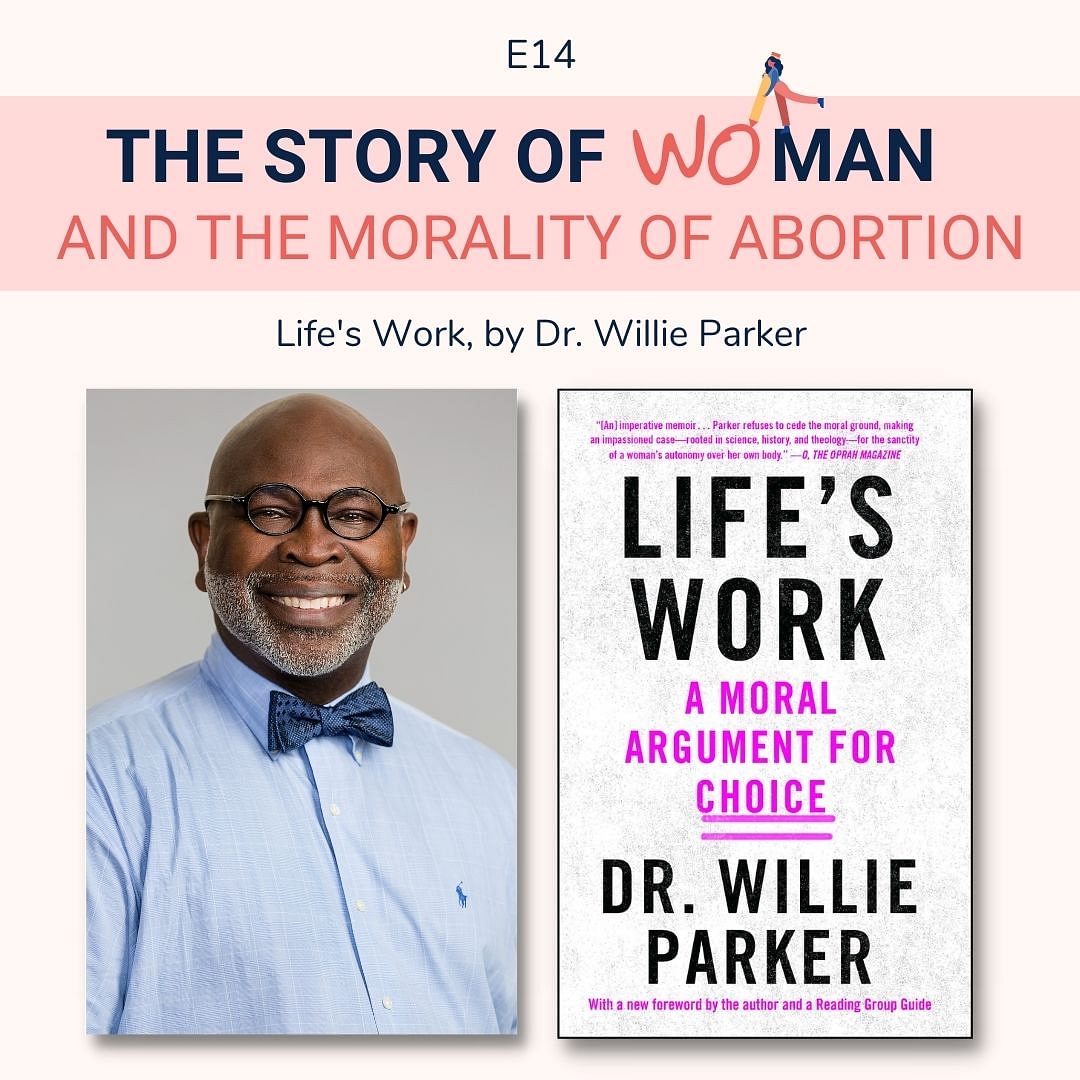

And now for today's guest, I think there are few people better positioned to talk about the morality of abortion than my guest today. Dr. Willie Parker. We are discussing his book. Life's Work A Moral Argument for Choice. Dr. Parker is an OB GYN specializing in abortions. And as a reproductive justice advocate currently providing abortion care for women in Alabama, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Illinois. He holds degrees from the University of Iowa College of Medicine, the Harvard School of Public Health, the University of Cincinnati and the University of Michigan. He is board certified in obstetrics and gynecology and trained and preventative medicine and epidemiology through the centers for disease control, the CDC.

His work includes a focus on violence against women, sexual assault prevention and reproductive health rights through advocacy, provision of contraceptive and abortion services and men's reproductive health. And this guy's accolades and accomplishments just go on and on. He is the chair of the board of Physicians for Reproductive Health and a board member of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice. He was recently honored by the United nations office of human rights. He also received planned Parenthood's Margaret Sanger award, the organization's highest award. And he received the champions of choice award from NARAL, the oldest abortion rights advocacy group in the U S and on and on and on.

And on top of that, Dr. Parker has been a practicing Christian since he was a kid growing up in the deep south and living in a Christian household and community. This guy is incredible and I am in awe of his work and how he speaks about these issues. I mean, his email signature is Namaste , so just so many good vibes.

In our conversation today, we talk about the upcoming Roe V. Wade decision and what these last few weeks, since the leaked draft decision have been like for him as an abortion provider in the south and Midwest. We talk about his upbringing in the deep south and how his race and religion have influenced his perspective of what his patients are going through. We talk about his decision to start performing abortions, how he went from not performing them to seeing it as his moral duty and calling in life. We talk about what the Bible has to say about abortion, or a lack there of. And we talk about the women who find themselves in need of his services along with what will happen to them when Roe is overturned. And we end on a more positive note talking about what gives him hope for the future.

In Dr. Parker's bonus Patreon episode, you will get to hear him talk about what it's like traveling all over the country to provide women with the basic healthcare that they need. You'll also hear his response to my question about if he fears for his life, given that harassment ranges from name calling in parking lots to assassinating abortion providers and setting clinics on fire. If that intrigues, you consider becoming a Patreon where you can hear all of this and more, but for now sit back and enjoy or be motivated by my conversation with Dr. Willie Parker.

[00:06:02] Section: Episode interview

[00:06:03] Anna: Hi, Dr. Parker. Welcome. Thank you so much for being here today. I'm really looking forward to this conversation.

[00:06:10] Dr Willie Parker: Greetings and thank you for the invite. Not to have been looking forward to having this conversation.

[00:06:15] Anna: So your work has always been incredibly important, but it is now acutely urgent in a whole new way with the upcoming Roe V Wade decision. And the fact that we all got a sneak peek as to how the Supreme court is likely to vote on that case. It's not looking good. So we're recording this on May 13th and the leaked draft decision happened about a week and a half ago. So before we dive into your book and your story, can you tell us what the past few weeks have been like for you as an abortion provider in the Southern and Midwestern states of America?

[00:06:54] Dr Willie Parker: Well, in the south Anna I grew up in Alabama and during the high point of the civil rights movement, right at the end of the sixties, right before Dr. King was assassinated when I was five years old. And as I grew up listening to the older folk, they would say, " In times like these it's always been times like these."

And for those of us who have been concerned and compassionately active around assuring the safety of women and pregnant people with regard to their reproductive life goals, we can say like Job, that that which we fear greatly has come upon us. We've always known this was possible because since January 22nd, 1973, there's not been a day where abortion rights have gone un contested. What's been steady, has been the build and the momentum to get to this moment where the thing that people are opposed to abortion have been consistent on task and on message for has brought them to the precipice of achieving their goal. What that's meant for people who are in a position to need those services has been almost like a hurricane warning.

When I lived in Hawaii, when they would have announced the hurricane was on the way that would be a run on the stores to try and get the things that you needed. And in a similar fashion, in the last week and a half, there's felt like six months, there's been a run on abortion services, if you will, in Arkansas, which is primarily where I provide, because Arkansas has served as a Oasis for people in surrounding states where the laws have been as restrictive as Arkansas, but at least in Arkansas, we still have the ability to provide care.

So women would come from Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, parts of Southern Missouri, Kentucky. So it was just a catchment area. And so if you look at five or six states where it's eminent that there will be no abortion services, there has been a run on those services. So we've opened up sessions where we're seeing women almost every day to clear out the backlog that had already built because of what had happened in Texas. It's been really, really busy as people are trying to get their reproductive health needs met before they lose their ability to do.

[00:09:10] Anna: Hm. I can only imagine what it's like to be an abortion provider in America right now. And we'll get into that a bit more and I want to come back around to Roe in the future of abortion and America at the end. But to start our conversation, I want to talk a little bit about your story and how you went from being a poor black kid in the south to a very prominent OB GYN and a fierce champion of women that you are today. So can you tell us a bit about your upbringing? What was that like for you and how did you kind of journey from there to where you are today?

[00:09:49] Dr Willie Parker: Sure. Well, your description of my arc and narrative is far more drastic than it was. And in terms of I did grow up in the south in abject poverty as a person of color, the south being the cradle of slavery. And so most of the descendants from our American experience with that residing there.

So I grew up in a situation of material lack, but not destitute. And by that, I mean, I think the critical inputs, safety and feeling cared for and feeling provided for to the best of the people who were responsible for me could, I grew up not knowing that I was poor until I applied to college per se.

And there was an income and family size metric. And when I say I'm being tongue in cheek, I knew that there were things that we didn't have that we wanted and some things that we need it. But there were six of us. My mother was a single mother. We grew up wanting for ourselves, but everybody else wants, we wanted, you know, security. We wanted some creature comforts, and when we could have those things we did, and we didn't my mother made sure that I understood that there were things that we didn't have, but there was nothing that I was entitled to. So, you know, you can't take from others, you can't lie and what you have, you have to be diligent and responsible for.

So those were the core values that I was reared with. And I think those things were trascendent of material things. So, I had a happy childhood, so there was no sense of pitying me, which people when they hear my stories. Oh, no, you grew up. How did you do it? Well, you know, I persevere one day at a time.

My mother and the folk in my community took care of us. And so when I was no longer living in poverty after having the chance to go to college and then medical school, my sense of values were still rooted in my upbringing. And so changing socioeconomically didn't change my values as much. And part of the upbringing was also my conversion experience as a Christian at the age of 15, which was the first time they really gave me hope that because faith and religion are in my DNA, I embraced the sense that there was a purpose for my life.

And so all of those things were instrumental in shaping me and putting me in the position to have my crisis of conscience that later resulted in me becoming an abortion provider, because I had to really wrestle with what it meant to be an abortion provider or contemplate what it meant to be a women's health provider. And putting that in the context of having, been reared with a fundamentalist Christian understanding that it was never explicitly against abortion in the black community, but eventually with a literal interpretation of the Bible raised the question of whether or not if abortion ends a life, is that murder? In the Bible says thou shall not murder. So by extension now shall not do an abortion.

[00:12:51] Anna: And I want to ask you about your faith in a minute, but first, one more question, kind of on your Southern upbringing, I've heard you compare the fight for reproductive rights, to the fight against slavery. So I'm curious, how does your race and your upbringing in the south influence your perspective on what your patients are going through?

[00:13:13] Dr Willie Parker: Sure. You know, when I thought deeply about what it is I'm doing as an abortion provider and how that it's an act of liberation for people in the position to need that. I thought deeply as a student in American history, but of Southern history and of black history and the interface between those things when they get falsely separated because black history is American history.

I thought about something that Dr. King said, when he talked about why slavery was immoral. And he said that the moral infraction of slavery was that people were relegated to the status of things. And I had an epiphany around when we reduce women and pregnant people to their reproductive capacity to bring forth young as that only people with a uterus can do that, when we decide that there is a public interest in that person's reproductive capacity and in their uterus that goes beyond or runs counter to the interests of the person who has the uterus, that person is relegated to the status of a thing in the same way that black people relegated to machinery to produce cotton for the wealth of this country. So thus the violation of their human dignity and their rights to be self-determining, which is innate because Dr. King said human rights are rights that are neither derived from nor conferred by the state. The only things the states can do is protect your human rights. They can't give them to you, uh, you were born with them. In the same regard, when we restrict a woman's, or a pregnant person's, ability to decide when and whether or not to procreate and to become a parent, we have reduced the status of their humanity.

And that is a, in my opinion, a moral infraction. And that's what makes it universally wrong, no matter who says it's right, or no matter what the law says.

[00:15:01] Anna: Absolutely. So I want to talk then a bit about your faith and, you know, you alluded to this, your decision to begin providing abortions because you didn't always provide them.

So can you kind of walk us through why you didn't want to provide them. And then what changed your mind?

[00:15:19] Dr Willie Parker: Sure. Well, I think that the most succinct way that I can describe it someone want to say, when you wrestle with your conscience and you lose, you actually win. And so for me, the wrestle of conscience, which is a thoughtful, contemplation rooted in the center of my values that are derived from my understanding as a Christian, but also as my upbringing, I came to a point of crisis when I finished medical school and chose to become a women's health provider as an OB GYN doctor. Invariably, it put me in a place where I began to see women who were pregnant and didn't want to be or pregnant and shouldn't be because it was a threat to life. And when I began to think about my identity as a women's health provider, it had to happen in the context of me having, become a born again Christian at the age of 15.

So, I had to wrestle with that and that wrestle with conscience came to a head when I was listening to a sermon by Dr. King, where he described what made the good Samaritan good. And in that story, he took a passage of texts. He did it several times, but the one time that he did it was on the last night of his life, April 3rd in Memphis.

And he said that Samaritan or a person who wasn't from that community happened upon someone who had been robbed and beaten. And the person who had no communal or nationalistic obligation to help somebody found on the side of the road, stop and help the person. And Dr. King use that story to say that what made the good Samaritan good was that, whereas everybody else asks what will happen to me if I stopped to help this person, the Samaritan reversed the question of concern and ask what happened this person, if I don't stop to help him. And as we do with every sacred texts, we read ourselves into it and find our meaning and purpose when we see ourselves in that story. In that story, I became the Samaritan, pregnant women with the need to end the pregnancy became the fall of traveler. And so like the Samaritan for me, the question became as a women's health provider, what happens to pregnant women and pregnant people if I, as a women's health provider, don't help them? And so then my understanding of what it means to be Christian and to be compassionate, had to reconcile those two. And for me, the only compassionate position to hold as a woman's health provider, with the capacity and the ability to do something for somebody in that situation, was to provide that care.

So, whereas many people have to become comfortable providing abortions when they do their values clarification, I became uncomfortable not providing their care when I know what it meant when women didn't have it, because I know about maternal mortality. I know about the severe other issues that come up when women don't have access to abortion care.

[00:18:15] Anna: I love that story. It's just such a simple and subtle shift. What will happen to me if I stop and help them versus what will happen to this person, if I don't stop and help them? And speaking of sacred texts, you know, a lot of political messages that we hear about are grounded in language of Christianity and religion.

And, you know, you've mentioned the reference of thou shall not kill, but I'm curious, what does the Bible say about abortion? About this issue?

[00:18:46] Dr Willie Parker: Well, oddly enough, the Bible says very little about abortion. When I say oddly you would think that the way that the Bible is bantered around as the authoritative moral platform upon which our laws are founded. But There are only a couple of obscure references, and then there's the kind of a hijacking of some literary devices to make it fit the theology that we've developed very recently in this country to villainize and to turn abortion into a moral issue.

I say that abortion became immoral in American 1980 because of the rise of the moral majority as it pivoted from segregation and Jerry Falwell, and those guys who stopped public education for black people in Virginia once brown V board passed. And it's hard to talk about these issues without having a historical context for.

[00:19:43] Anna: Yeah.

[00:19:44] Dr Willie Parker: The happy meal is older than opposition to abortion in America because the happy meal was created by a McDonald's in 1979, the moral majority declared abortion, immoral and illegal in order to get Ronald Reagan in office in 1980. What they did was, I call it the unholy alliance, Protestants who otherwise deemed Catholics reprobate latched on to the notion that birth and marriage are sacraments in the Catholic church.

And they consider anything that disrupts procreation immoral and sin. Protestants, you know, again, the moral majority have latched on and decided that we can move people to vote against their interests or the way we want them to, by having them thinking we are going to restore America to his original position as God's chosen nation, which factors into manifest destiny and how we got this country and what we think is owed to certain people.

But the Bible doesn't say much about abortion. There is a reference to pregnancy loss in the old Testament where if two men are fighting and the spouse of one of the men gets injured during the fight, and she loses the pregnancy, the person who was in conflict with the father of the pregnancy owes him a compensation for a property loss. So it's a tort issue.

But if the woman dies, then it's, eye for eyes is the penalty for murder. That person will be, subject to death. So the whole morphing abortion to murder when using that reference, it doesn't, you know, the ending of a pregnancy does not constitute a murder. Right. And then the other passage and I'm sure people can go and look these things up if they want, there was a test of fidelity for if a woman was accused of adultery and the priest would confront her and then they would take some dust and mix a concoction, and the woman would drink it. If she was lying, she would abort, and if she was being truthful, you know, nothing would happen to her pregnancy. So again, the only two references that I know of that have anything to do with the outcome of a pregnancy, explicitly, are there and people again took those references and morph them into what they needed them to say in order to make abortion a moral issue.

And so it was with that understanding as a Christian, who understands that my faith tradition is rooted in the same faith tradition of people who are opposed to abortion that allows me to have respect and compassion, but not to capitulate when it results in the harm and the devaluation of women and pregnant people.

[00:22:37] Anna: Absolutely. A point that I wanted to kind of get to next. The whole idea that life begins at conception. You know, I think that's a main talking point of the anti-abortion side and I'm curious as a medical provider and as a person of faith, your thoughts on that argument, generally that life begins at conception and that's that.

[00:22:57] Dr Willie Parker: Sure. I've had to think about that. And I continue to think about that. And as I approached my sense of purpose and calling around doing this work and my craft as a physician, I continually think and rethink my position because I, it doesn't require me to have an absolute understanding that I'm absolutely right, and everybody else is absolutely wrong, but I am operating from a place of conscientious and sincere practice rooted in a compassion that I think is non-negotiable for people on this issue.

And so it also requires me in order to deescalate to not be inflamed. When I think about this, I try to think about the ways in which to reconcile these understanding and I was adventurous enough. I was going to say foolish enough, but I was adventurous enough to participate in a couple of debates about the whole notion of the morality of abortion or when life begins. And one of the ways that I try to help people understand and paint a word picture is I saw a meme once where a woman and a man were having a conversation about how life begins and where babies come from.

And the man renders a religious understand. He says, you know, you came from my rib, intimating that the creation story, Adam or man was made first and his rib was taken and woman was made as a helpmate. And the woman looked at him and said, I didn't come from your rib. You came from my vagina. And it is the tension between a biologic understanding of reproduction, people come from pregnant people's vaginas. And in this country now 36% of the time they come through an incision in their belly, or people come from other people's body parts. Now, one is a scientific understanding of one's religious understanding. The two understandings are not mutually exclusive, but neither are they interchangeable.

[00:24:16] Anna: Hm.

[00:24:16] Dr Willie Parker: And I say that because the false tension between science and religion, if you say life begins at conception, what you're violating is the idea that life is not an event. It's a process.

[00:24:29] Anna: Hmm.

[00:24:29] Dr Willie Parker: Life began a long time ago when the things that we recognize or any of the attributes that we define as life, being able to reproduce, consuming energy, needing to replenish that energy, coming into a reality by a birth process. Some things aren't born they are spawned, you know, and then dying and exiting this process. So life and death are parts of a whole process. And so it's an interplay between multiple events, conception being one of them, death being one of them, maturation being one of them. And so when somebody tells me that a life begins at conception, I say, I respect and understand what you're saying but that's not a scientific understanding of reproduction. And so we can honestly disagree, because I can't rebut your opinion or your belief. You're entitled to hold those. But if we're going to make policies which other people are duty bound to honor, then we have to have some objective standard and criteria and a scientific understanding, when it comes to reproduction, should be what drives policy and not simply anecdote. I think Dr. King said it best about the false tension between science and religion. He said the science is mankind or humankind knowledge, which is power. Religion gives humankind wisdom, which is control.

Science deals with facts, religion deals with values. The two are not mutually exclusive or the two are not enemies. And so it's only when we insist on an absolute or inimical relationship between science and religion that we end up with these conflicts. And then it comes down to a question of which paradigm wins. So it really says in a world that's complex and pluralistic, where we now have scientific knowledge alongside, religious understandings of the world, one tradition can't invalidate the other because if the fundamental is win and we are required to overlook what we know to be true in reality, then we're all in peril.

[00:26:35] Anna: Hmm. Love that. And I want to ask you about your life, being an abortion provider, but I have one more question kind of on this path. I know language is very important to you, as it should be, because it's a very powerful and sometimes dangerous tool. But I was wondering if you could talk about your reframing of the use of the words pro-life and anti.

[00:26:57] Dr Willie Parker: Sure. When I began to think about the narrative of pro-life pro-choice, it didn't work for me because it didn't capture the nuance of how I think about this issue. I am pro-life and I am pro-choice and those aren't mutually exclusive, but it requires some precision to the language.

When I say I am pro-life, I promote life and it's process for everybody, for people. When a woman comes to me and she's pregnant and she has a life process going on in her, I promote what I call her reproductive life goals. If she's pregnant and she doesn't want to be, oh, she's pregnant and she's too ill be pregnant, I think I am pro life. I am pro the life of that woman. And I am pro the life of her fetus if that's what she wants. Cause I'm an obstetrician gynecologist. I can help her continue her pregnancy. And as an abortion provider, I can help her to safely end her pregnancy with dignity and respect.

I am pro choice, which means I support the ability of somebody to make decisions about their life. I think part of the static in the tension that's created by that framework is choice introduces the notion of a frivolity into the decision-making of a pregnant person. A choice is when you have two options or two outcomes and they're at least neutral or equally acceptable to you. I think we should be talking about resolving dilemmas. When you're pregnant and you don't want to be or you're pregnant and it results in a hazard for you. A dilemma is when you have two options, neither of which is really what you want, but you don't have the liberty of not deciding.

When I say I'm pro choice or pro life, changed the prefixes. It is you are either anti-abortion or you're a pro abortion. Nobody's pro-abortion in terms of promoting abortion, I'm pro abortion the way a cardiothoracic surgeon is pro-heart trans. A cardiothoracic surgeon does not want anyone to have cardiovascular disease that progresses to the point of needing to have a heart transplant, but in the quest to preserve the life of the patient in front of them, they want somebody to be able to have a heart transplant if they need it.

And I'm not being flippant and loose or minimizing the deep seated feelings that people have. And even that they hold their beliefs sincerely, but language matters. And I think part of the tension and the intractability of our efforts to find common ground, which for me has been a problematic notion because if the common ground on which we stand has to be the life and agency of a person that we're making a decision about what they can do with their body and their lives, I'm not willing to stand on that ground. But if we can stand in a place where we can honestly disagree and recognize that we cannot triangulate or infantilize or subordinate a woman, or a pregnant person in their life, then we can talk all day long and we can reach some honest understanding because Gandhi says that's the beginning of disagreement.

So I had to understand that there's nothing mutually exclusive about me being pro-life and pro-choice, pro reproductive rights. I don't even like the term choice, again I think it trivializes what people were making a decision about whether or not to enter pregnancy is doing, you know, I didn't choose chicken or steak for dinner.

You know, that's not what they're doing. They are resolving a dilemma. They are caught in a place where they are not in control of their lives. The ending of this pregnancy at this time is the option that resonates most deeply with them as they exercise their right to make a decision about what their lives should mean.

[00:30:48] Anna: Couldn't agree more. So I want to talk about your life as an abortion provider, on a more philosophical level, you know, what does being an abortion provider mean to you?

[00:31:00] Dr Willie Parker: Sure. Well, for me being an abortion provider was the next logical step as I've sought to integrate my life by always returning to the question of what is this all about with regard to life and why am I here? Becoming a Christian first and having that be core to my identity. And then initially, being told that that identity was mutually exclusive to responding to the compassion I felt for women after I became a women's health provider, I in, invariably understood my Christian understanding differently because my conscious level really believed or concluded that morally I was acting inappropriately or was acting against the purposes for which I believe I'm here.

I would not have become an abortion provider. That's why it took me 12 years to do the values clarification. So once I became an abortion provider, it for me became the bringing into focus, my core values as a human being, my religious values rooted in compassion and a faith identity of Christianity, my intellectual rigor and my evidence-based and reality based approach to my life as a physician.

And for me, the way that all those things came together was as an abortion provider, it allowed me to bring my politics of human rights and human dignity and providence for all human beings so that they have the things they need to live with dignity, my religious values of feeling morally obligated to I love my neighbor as myself as a reflection of my love for God.

So morally, politically, religiously, it all came together and I saw my purpose as being there and helping somebody that no one else is willing to help me. That's the deepest sense of compassion. I had to move from sympathy or simply feeling bad for somebody who's in a hard situation.

And I think empathy is a part of compassionate action, but there's only so much empathy I can have as a person without a uterus. I don't know what it's like. I will never know. I can't put myself in the shoes of somebody who has a life process germinating and gestating inside of them. And since I can imagine what it's like to have someone deny you the ability to make a decision about your life, whether it be tying your shoes or what you want to have for dinner.

But I can't imagine somebody telling me that I can't do something for myself and to myself that has no bearing on anybody else. And yet I am prohibited because I've been turned into property in a public interest. So abortion provision for me is the clearest understanding of my purpose, given the choices I made about my career and that's how I've approached it.

And so it's not What is your purpose? I found mine. Howard Thurman says we don't need to ask what the world needs. He's a theologian who influenced Dr. King greatly, he said nobody needs to ask what the world needs. He says, every person needs to find out what is the thing in you that moves you the most and do that. If you find that thing and you do that, the world is going to be better off.

When I became an abortion provider, that was the thing that moved me. And And I believe that I won't be so grandiose as to say the world is better off. I do know that every woman that's asked me to provide this service for her, where I've been able to safely provide it for her, she has been better off. And that's been, to me, in that moment when I'm with that woman, she's the world.

[00:34:38] Anna: That's a great segue because that's exactly who I want to talk about next is the women and those who seek abortion services. So I want to learn more about them from your perspective. So to start, you know, there's this rhetoric that women who seek abortions are irresponsible and reckless in their decisions. So I'm curious, what has been your experience with this line of thinking.

[00:35:05] Dr Willie Parker: So for the women who have abortions, Anna, if the people asking that question, especially if they're female, if they look in the mirror, you are looking at women who have abortions. They are at various stations in life. I've done abortion for affluent women, for women in abject poverty, women of all races, women of all different religious backgrounds or non-religious traditions, women of different sexual orientations. My experience is everyone that I've seen is a mirror. Every woman that I've seen is me and any person who's musing about who women are who have abortions is simply just look in the mirror. They're complex individuals, just like you.

So part of our ability to impose harsh penalties or to be indifferent to suffering a folk is when we fail to recognize that we could be in their situation. That is a Jedi mind trick that we play with ourselves. The women who have abortion are you. And if I had a uterus, it would be me.

Now, the demographics about who shows up in public spaces to have abortions, tell us that women who have socioeconomic challenges, women who have lack of access to medically accurate sex education, women who have lack of access to modern methods of contraception and family planning, those are the women who have unintended pregnancies. Abortions come from unplanned, unwanted pregnancies or wanted, but lethally flawed ones. Abortions don't come from what, skin color you are, what community you come from. So women who have abortions, looked like whoever's looking in the mirror to ask the question.

[00:36:47] Anna: I liked that way of thinking about it. Cause yeah you're exactly right. People, I think have a habit of distancing themselves and creating this narrative of who they think people who have abortions are, but as you say, it's you it's everyone, you know, everybody loves somebody that's had an abortion. That's one of the lines I like. So I imagine you have, you know, obviously everyone is different. No one's story is going to be indicative of all patients. But I imagine you do have a lot of stories about your patients. Good and bad. And I was wondering if you could share one of those with us and I'll kind of leave it up to you to say which one, but any that might help us understand the reality of life for these women and people who seek your services.

[00:37:32] Dr Willie Parker: I can think of two cases recently, you know. First of all, everybody has a story and everybody's story is relevant to them. It is the story that led to them, making the decision to seek the care that I provide. But two cases that I saw recently. In the last couple of weeks there's been such a backlog at the Arkansas clinic with, I mentioned earlier where we're seeing women from surrounding states, many of them, those women from Texas, cause it's the next state over where women have had all kinds of situations, that prompted them to consider ending a pregnancy. I just recently saw young woman who was, think she was 17 weeks pregnant and had the diagnosis of a heart malformation where the heart only had two chambers for the fetus.

And so even though she was 17 weeks, the pregnancy was not viable because as even the most elementary person knows, that human hearts have four chambers. So that heart's missing two parts. And so at 17 weeks, the pregnancy is farther along and because the placenta or the afterbirth is what supports the pregnancy, pregnancy can continue to grow and develop even with a heart that's only half of what it should be. And at 17 weeks it was a very much a desired pregnancy. But in all of the evaluation, when the woman finally got the final, that this is not a mistake and many times, especially in a desire pregnancy, people are hoping against hope.

So they will find out as early as they can. And then they'll get specialists in second and third opinions. And at this time the pregnancy is still growing. And so they end up a little farther along, which is usually the case with most of the later gestational pregnancies. It's usually a late diagnosis of a problem, or there's a maternal health issue that's being worse.

And but those represent only the 2.5% of pregnancies. But in this lady's case, it was a very much, a much desire pregnancy. And she was a first-time mom. One of the things that people fail to recognize is when a pregnancy is fatally flawed, even if they carry it to term that pregnancy is not going to survive. As long as that woman's pregnant or that person's pregnant, they incur all the risks associated with pregnancy. So in this country, right now, we're in the middle of a rising rate of maternal mortality. So people always see at the point of conception, a baby in the bassinet and a healthy mother going home, having knitted booties.

But right now in America, women are dying in the context of pregnancy. They're dying simply because they were pregnant. So if you take that, understand that maternal mortality is increasing in that risk, is there, as long as that one was pregnant for someone to say that this woman who has lethally flawed pregnancy at 17 weeks is obligated to continue it because it is offensive to some people's religious understanding that she disrupt this pregnancy, it's to fail to understand that this woman is being forced to take a risk that no one should obligate her to take. So part of the utility I have, rather in addition to preserving a women's autonomy, but it's to mitigate risks that's associated with this process that is going on. So that woman we safely terminated her 17 week pregnancy because the pregnancy was lethally flawed.

The other story that stands out, is a young woman who was 12 weeks pregnant who had an orbital fracture and had her face reconstructed. And she's 12 weeks pregnant by her husband who did that. And, was in an abusive situation at the time. And I don't know if this pregnancy was a force conception because many times in an abusive situation, female partners are denied access to contraception.

One of the ways in which women are controlled in that situation is that they are repeatedly impregnated and made vulnerable socio-economically, but also physically because they're pregnant, but this woman had an orbital fracture, had been battered by her husband and decided to terminate this pregnancy because she was in jeopardy. And she had three kids and, you know, whether she knew it or not children in domestic violence situations are often battered as well. So there's a situation where a woman could have continued to pregnancy, but for her life, wellbeing and purposes chose not to continue.

There was a woman who wanted the pregnancy, but ended the pregnancy as an act of compassion, not to bring a baby into the world that would suffer horribly while not living long, as well as the possibility that with the complications from this pregnancy, she could lose her uterus and lose her capacity to try again.

There all kinds of circumstances, but equally important is the 19 year old who had unprotected sex and became pregnant and chooses not to continue the pregnancy. Her story is no less important than no less compelling than the other two that I just gave you. You know I grew weary of giving the tragic narrative because it was an indirect validation of the sense of we know who gets pregnant, who doesn't. We know who deserves to have an abortion, who doesn't.

It's almost like a kind of an abortion pornography. And that's a really a stretch of using the concept, but the kind of exaggeration of what abortion is, uh, is not this crisis oriented tragic. Oh, I tell my patients all the time when I do what I call dignity restoration with them, because women are beaten up women and pregnant people are beaten up and they are vexed because the people standing in front of the clinic have them thinking that they're doing something immoral.

And most women who come have a faith identity. So they're being made to feel like they're acting outside of the context of their faith. And indignity restoration, I kind of what I call rightsize the reality of abortion. I tell them that an abortion is not a bad thing. It's not a good thing. It's a thing. It's a decision that anybody pregnant has to make. It's a decision that only somebody pregnant can make, and whether somebody's pregnant, made the decision and regrets there's, they don't have a right to tell you that you will regret yours. So when you're thinking clearly about it, you have to trust yourself to act in your own interest, to understand that good women have abortions every day.

And this decision will not define you. This is a choice you're making and you are not defined by this single decision. It may be a complex one for you, but if you're sitting in front of me right now, your ability to get that tough decisions is a hundred percent. You have a hundred percent success rate.

You've made it through tough decisions and you'll make it through this. But I really pushed back on the notion of the tragic narrative around abortion, because it further infantilizes women in their decision-making. It says that we have to have a caretaker role around them making a decision that even, you know, you don't have to be a highly educated person to know what you want to do with your life. And to know that there's something happening to you that you don't want to happen and you can choose otherwise.

[00:45:10] Anna: Absolutely. Amen. So what do you think will happen to these women, what will life look like, if, and dare I say when Roe is overturned?

[00:45:22] Dr Willie Parker: Well, one of my mentors, Dr. Josh, who's now probably close to 90, but was for a long time the chairman of OB GYN at Northwestern university, I met him when I became an abortion provider and just admired him because he is living history with regard to the abortion rights movement. He was one of the original signatories in 1972, before abortion became legal of 100 OB GYN doctors talking about the necessity and importance of abortion being made legal because he had come to an era where they had seen a women die from unsafe abortion.

And Dr. Shara said something that just struck me about the significance of the back and forth and the laws and all of that. He says, there's not been a law yet that's been passed that will stop a woman from ending a pregnancy that she doesn't want, whether abortion is legal or illegal, women are going to end their pregnancies. The legal status of abortion determines whether or not a woman can do that safely. So when Roe is overturned, all we will do is increase the peril associated with reproduction in this country. And we will see women die. There will be consequences. There will be mortality. There will be morbidity.

Women will act in their own best interests, whatever that means to them. When Patrick Henry said, give me liberty, or give me death, we celebrated as the founding of this country, because it was the acknowledgement that free men and men of conscious, they would rather die if they could live on their own terms. When a woman and a pregnant person decides that they will end up pregnancy, no matter what the law says, they're making the same declaration.

Give me liberty, or give me death. I will be free. I will make my own decisions. I will live with the dignity of a full human being or I will die in the person. So we will see carnage. Who will it be? It will be who it was before Roe. It will be black and brown and poor women because they will be the people who don't have the ability to travel to the remaining 12 to 14 states that will provide abortion care.

They will be the women who are in states where people will try and imperil even the option of getting access to medication abortion to self-manage. We will see, we will see outcome of this decision and those of us who have not fought hard enough may have some regrets. And the restoration process will be that we will have to work through the political process to restore this right, as a human right.

And not leave it vulnerable to a loose interpretation of the constitution around whether or not it's a privacy right. But we will say it is essential healthcare. We need to have a constitutional amendment around healthcare and all the other things that should be non negotiable and not vulnerable to the political process.

So there's, what's going to happen politically. I think the pendulum can and will need to, and just swing the other way, may not in our lifetime, but it will need to happen. Maybe this will arouse people to understand that democracy is participatory and that they can't rely on the inevitability of abortion access remaining and being beyond a salability cause now we know that it is not. But for the people until that happens, those of us who know what happens when women don't have access, we will have to engage our consciousness and where those of us who were actually abortion providers, who are physicians, where we might have to end up as a what the future looks like.

If I can explore that in countries like, it's in south American countries before abortion was legal, in countries like Argentina and some of the other countries where it's now become legal, that's the paradox and the irony. Places where abortion was illegal has now because of the evidence-based practice and people politically making half of what needs to happen, abortions become legal in countries where it was illegal.

And now in this country where abortion has been legal for almost 50 years, it's about to become illegal. In those countries when abortion was illegal, health professionals had a moral and ethical obligation to do what's called, if you can't do prevention as a public health a concept called harm reduction, how would we do harm reduction in this country for a pregnant people and women in the states where it's illegal. will never be illegal for you to diagnose a pregnancy and to establish how far along it is.

It will never be illegal for you to tell a woman what her options are. Some states might try and make that, but I am ethically bound to do non-directive counseling, to give every person their option. That is a medical tenant as a basic ethic in medical practice, that you have to do non-directive counseling and give people the information to talk about a pregnancy without talking about, abortion or the risk is unethical.

And so their states have required doctors to be unethical because they prohibit you from talking about t he consequences of pregnancy or the option of ending one. So in many places we've already been post-Roe for years, I would argue Mississippi has been Post-Roe, Alabama, many states because women have had to travel.

Mississippi went from 14 clinics to one. So we've been post-roe and a lot of places, there's some states that don't have an abortion clinic. We've been post-roe for awhile. So now what's going to happen is the plight that has visited poor people and brown people and black people will now visit more people. Hopefully people understand that you can never sit by idly while I focus suffering. Because when you do that, eventually you will suffer. So, we will have to figure out how we are going to get women to safety. How are we going to each of us look within ourselves and if we decide that this is wrong, what are we going to do about it?

But doctors, again, it will be harm reduction and giving women their options and telling women that there is a clinic in California. There is a clinic in New Mexico. There's a clinic in Illinois, you know, but now we're in a space where even more so than before a person's access to their reproductive rights will depend on the zip code.

[00:52:09] Anna: Yeah. So what do you wish people who are against abortion understood. You know, if there was someone sitting across from you right now and you were trying to get your point across,

[00:52:20] Dr Willie Parker: Sure.

[00:52:21] Anna: what would you say to them?

[00:52:22] Dr Willie Parker: I would say to them, I respect deeply your position. Honest disagreement, it can be the beginning of a progress as Ghandi said. I would say to them, we're all entitled to our own opinion, but nobody's entitled to their own facts and the facts are that abortion saves women's lives. And, I would also try to help them understand that the people who have abortions are not thoughtless careless in irresponsible.

For them as a thoughtful and especially for people who were in tragic circumstances, it is a loving decision. And I know that those are terms that because you've placed the reality of abortion and a scientific understanding of reproduction outside of your approach to questions about reproduction I would ask that you at least have respect and compassion for somebody who makes decisions that you don't agree with never lose sight of the humanity of the person, you know.

As an abortion provider, if I was talking to a person whose faith identity is the same as mine, I get that we don't agree. I would ask you to frame our disagreement in the form of a sibling disagreement. Siblings argue, and they disagree with one another, but they don't kill each other. The only person can kick you out of the family is the parent. And so I'm a Christian, you're a Christian. You might disavow my Christianity, but I'll never disavow yours.

You may just evaluate your relationship to me, but I'll never disavowed my relationship to you. So I asked that even as you disagree, that you think deeply about your disagreement and make sure that you don't lose your humanity and become cruel and inhumane to people who either have abortions of people who provide them simply because you don't agree.

[00:54:12] Anna: And what can we do to support you and your work and these women and people who seek your services now during this time, what can we do as, as listeners and individuals?

[00:54:25] Dr Willie Parker: For people who are in places where they're secure, whether it's food security, reproductive, decision-making security, some of us adopt missionary zeal, and we always want to help those people over there. Right. But somebody said the best way to make change in the world is to do what you can with what you have, where you are. The battle, for lack of an analogy, I've been trying to find other metaphors and analogies other than war, but the tension and the struggle for reproductive rights and human dignity and I really wanna frame abortion and reproductive decision-making in the context of human rights. Because it's when we lose our sight of the humanity of people who are seeking those, that we can do harm.

I would say that all politics are local. In London, the best way to help somebody in America is to understand, and to raise your voice, to make sure that Boris Johnson doesn't glad hand somebody who is about to take away reproductive rights and the slope that allowed us to get to this point was people deciding that they were upset about a black president, saying we got to take our country back and it created the political momentum and the power to coalesce folk who see the world a certain way to actualize their sense of how the world's supposed to address.

And it's fine if the way you think the world is supposed to operate, governs you, but the problem is their sense of how the world is supposed to operate governance everybody else. In America, dangerous conflation of religious identity and politics has meant that America's identity as a Christian nation and thereby validating Christian supremacy has allowed folk to hijack the political process and to undermine the democracy that if we all participated as a pluralistic country with people who basically seek and recognize and want human rights, we would have different policies.

I think the final thing I would say, if we adopt the logic that Abraham Lincoln adopted when somebody asked him why he freed the slaves and the civil war was complex. But Abraham Lincoln said simply when asked why he freed the slaves. He says, as I would not be a slave, so I will not be a master.

Those of us who cannot become pregnant, whether we be post-menopausal women or men or people without a uterus or people whose uterus no longer works, have to be unwilling to impose a tyranny on somebody else that we would not accept for ourselves.

[00:57:25] Anna: Love that. And I was going to say, I would like to end on a positive note. I mean, that kind of was a positive note already, but I want to end on a positive note if that's possible because I think, you know, a lot of us are feeling quite disheartened now about the future and really the world in some cases, but what gives you hope for the future? How do you think we can stay optimistic while remaining realistic

[00:57:51] Dr Willie Parker: Right.

[00:57:51] Anna: in this fight?

[00:57:53] Dr Willie Parker: I would say even if you don't know black history I think if people look at American history and look at the trajectory of slavery and what it took from, black people to go from captured Africans who were enslaved to now being a physician of a 30 year career during a podcast, talking about why you should not, uh, deny women access to abortion, the trajectory is there's always been a back and forth you know, in the attainment of human rights for black people, the back and forth was always a political when the laws would go forward and they would go back again, promptly people in my community say in times like these it's always been times like these, but what was not lost was the hope.

And the hope was always rooted in that my humanity is not up for debate no matter what the law says about it. And so until I have the ability to live my humanity fully, I'm going to fight every day. Didn't matter what the courts said. Didn't matter what the laws were. Those of us who are in pursuit of human rights, the battle doesn't change.

Dr. King said that when evil men plot, good men must plan. Now the world doesn't stratify, it's simply into an evil and good. Alexandra shows social needs had the difficulty in making that declaration that's the line between good and evil runs right down the middle of all of us. But when people are ill intentions plot, people with good intentions must plan. We have to continue to plan. We had to plan for a world when abortion access was legal. We have to plan for world when abortion access is illegal. We cannot modulate a lose our sense of compassion or duty around what it means to keep women and pregnant people safe.

So, the fights harder, the fights different, but Frederick Douglas says those who want progress have to be willing to fight. So the fight may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, but it's going to be a fight. So I am willing to continue to battle for the dignity of. And I hope people understand that just as abortion is about to become illegal, it can become legal again. Maybe we can get the Supreme court expanded.

Maybe I'm just being, I, I want to be, I can say I want to be apolitical, but I am political, cause life is political. Politics is the art of the possible, what is possible to preserve the life and the well-being of people who can become pregnant.

Those are politics. Partisan or nonpartisan. I don't care if it's Democrat or Republican. I will stand with anybody who understands that abortion is healthcare. Abortion is life saving and I will never give up on women and pregnant folk. I will continue to do what I can to preserve their dignity and to protect their wellbeing. And I think that's how you wake up every day, it'll tell you what you need to do next.

[01:00:50] Anna: Wonderful. That's a great note to end on. We are so thankful for you and your work. I am so thankful for this conversation. Thank you, Dr. Willie Parker, author of Life's Work. You are doing amazing things and I can't wait to continue to see what you do in this upcoming unknown future, but you've given us some hope to end on. So Thank you. so much for your time.

[01:01:13] Dr Willie Parker: Thank you. And thank you for having the, the mindfulness to have this conversation and to at least amplify the voices of people who are trying to call for a better world.

[01:01:25] Anna: Absolutely. Absolutely. Now go enjoy your barbecue.

[01:01:29] Overdub: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one-woman operation... so if you enjoyed this episode, there are a few small things you can do that make a big difference in helping other people find the podcast and allowing me to continue putting out new episodes!

You can subscribe, leave a review, share with a friend, follow us on social, become a patreon for access to bonus interviews and content, buy me a... metaphorical coffee which helps with production funds, or head to the website and check out the bookstore filled with 100's of books like this one. If you purchase any book through the links on the website, you support this podcast - and local bookstores! Soooo feel free to do all your book shopping there! All of these options are in the show notes.

Anything you can do is appreciated and makes a big difference in elevating woman from the footnotes of our story to the main narrative.

💌 Sharing is caring