[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Overdub: Hello, welcome to The Story of Woman, the podcast exploring what a man-made world looks like when we see it through her eyes. Woman's perspective is missing from our understanding of the world. This podcast is on a mission to change that. I’m your host, Anna Stoecklein Lau and each episode I'll be speaking with an author about the implications of her absence - how we got here, what still needs to be changed, and how telling her story will improve everyone's next chapter.

[00:00:34] Section: Episode level introduction

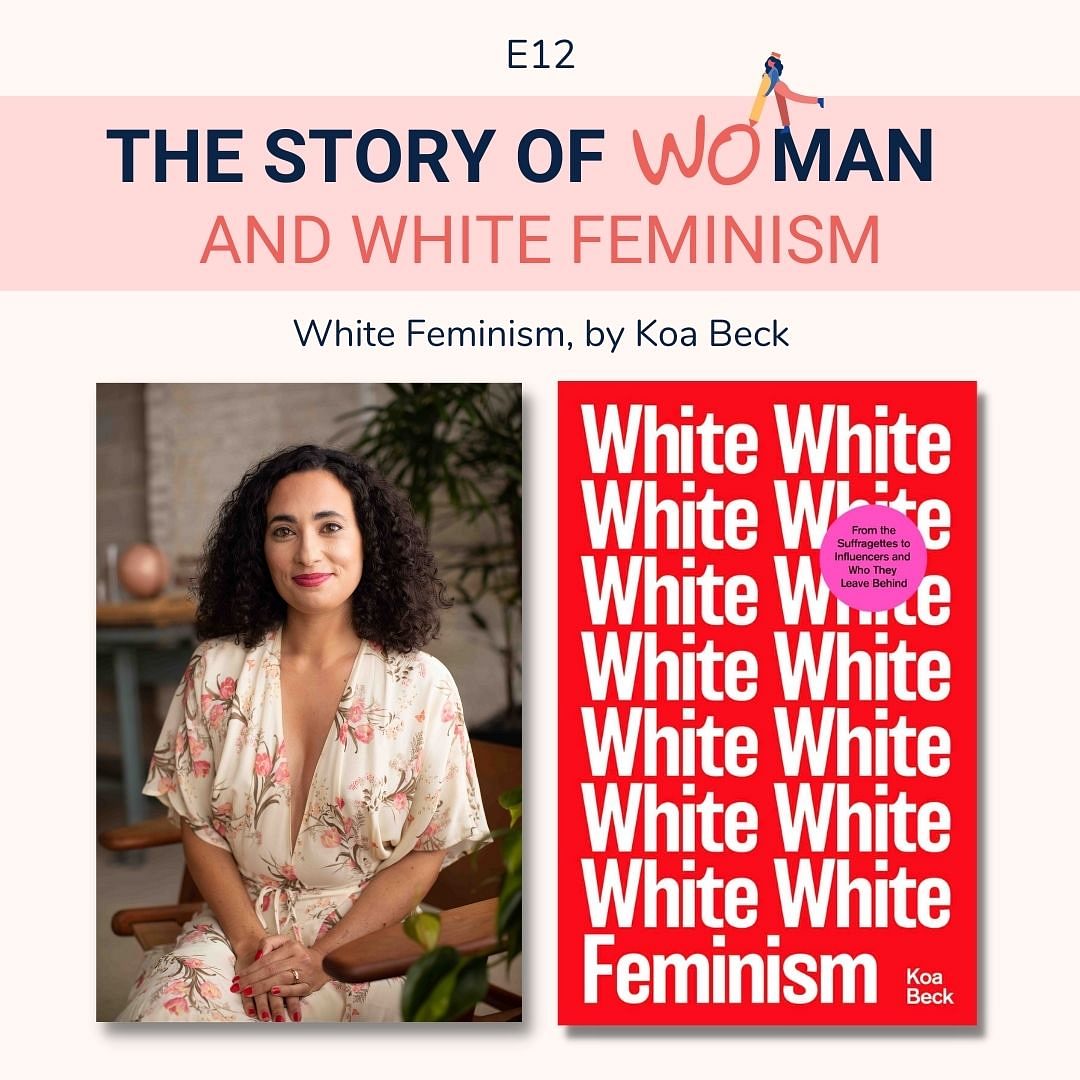

[00:00:35] Anna: Hello friends. Welcome back. And thank you so much for being here for the first post season one episode and what a great conversation we have to kick it off. I'm speaking with Koa Beck, author of White Feminism from the suffragettes to influencers and who they leave behind. Koa has previously worked as the editor in chief of Jezebel and executive editor of Vogue and as the senior features editor at Marie Claire, her reporting on gender identity, race and culture have been published in the Atlantic, time, the guardian, the New York observer, out, Esquire and many more.

In our conversation today, Koa defines for us, what exactly white feminism is. And she lays out how it's nothing new, but has been around for as long as the feminist movement itself has and how these two are often conflated.

We talk about who white feminism leaves behind and how it prioritizes mom preneurs over women who can't afford diapers. We talk about capitalism and the commodification of feminism. And what we can do to change things for the next generation. And if you think this kind of writing or conversation is divisive, well, we talk about that too. So stay tuned.

And through it all, if you start to feel uncomfortable in any way, perhaps you recognize yourself in parts of the conversation. I just want to say that that's the right reaction to have. Discomfort is a sign of understanding and growth and to read a line from Koa's book on this point, she writes: " Discomfort for the more privileged can be the threshold into increase awareness. It's the moments in which you shrink from that discomfort, that you don't walk through it, that you don't interrogate why you have such a corporal reaction to the demands of others, that those biases maintain their place."

And just to note on the podcast, regular listeners may notice a drop in the transitions that were found in the first season. If you have opinions about this change, good or bad, please do feel free to share them with me.

And one more thing to mention before we get into it, I'm trying out something new because I can't seem to keep these episodes shorter than an hour, which believe it or not is my goal. And because all the answers my guests give are worth listening to and keeping, I am starting a repository of bonus content that has all the good answers that had to be cut out for the sake of time. All of this content is going to be on Patreon. So for less than a cup of coffee, you can listen to extra conversation and help support the podcast. I really don't want to pay wall, but I do need to eat. And for those who can afford it, this will really help me be able to make more and better episodes.

In Koa's bonus episode, you get to hear her talk more about leaning in versus leaning on and how white feminism today, and a hundred years, ago has always merged very cleanly with capitalist metrics. You'll also hear what Koa is reading and what books she recommends.

There's a link in the show notes or on the story of woman website. So check it out. All right now for my conversation with Koa back, enjoy.

[00:04:01] Section: Episode interview

[00:04:02] Anna: Hi Koa, welcome. Thank you so much for being here today.

[00:04:05] Koa: Thank you for having me.

[00:04:07] Anna: So your book is called White Feminism, and I've heard you talk about how white feminism is this term that you saw thrown around and being used more and more in the public discourse, but that no one seemed to really know what it meant.

So I wanted to start there at the ground level. And have you define for us what white feminism means exactly, and also, can you tell us more about the problem that you identified in the first place that made you want to write this book and kind of set the record?

[00:04:39] Koa: Sure happily. So, as you summarized Anna, I come from the illustrious world of mainstream women's media. That's where I spent most of my career as a reporter and editor for 10 years. And, around the middle to latter part of my career, white feminism started to be a term that was popping up in more mainstream discourse.

I'm a big reader of gender theory and race theory and queer theory. And so white feminism, it's worth noting for the purposes of this conversation, has always existed pre me publishing a book about it pre you know, mainstream internet, deciding to publish and use the term. But notably it was the first time I had seen the term white feminism start to pop up in articles and blog posts on like pretty mainstream publications. And yet something I started to notice is that no two publications or no two authors or writers or proponents were seemingly using the term in the same way, nor could I trace, this is like, you know, 20 probably 17, could trace a concrete definition of what this was in, you know, usually pieces that were critical of say like a celebrity who said something, you know, really racially illiterate.

And so for me in going into this book and also trying to create a book that was a resource, I really wanted to define white feminism for you early in the text. I do it in the introduction to give you a real, concrete idea of what I'm tracing throughout the text. But also to show you how this ideology is specifically, that. It is an ideology, it's much bigger than, you know, the tone deaf, famous person who belittles the achievements of Serena and Venus Williams.

This, you know, much like racism or misogyny or homophobia, this is an ideology. This is an entire way of seeing. And so I'm asking you as the reader to not necessarily look at that particular person, but look at how their comments or, you know, a lot of their platforms elude and connect to this bigger ideology.

I define white feminism in my book as a very specific approach to achieving gender equality that pulls considerably from white supremacy, from labor exploitation, and a lot of capitalism as well as imperialism. And I trace that through the book.

[00:07:08] Anna: And this, because it's an ideology or a state of mind, it can be held by people of any race, any gender, is that right?

[00:07:16] Koa: Absolutely. I, again, in underscoring and analyzing this as an ideology, I'm of the opinion that really anyone can advocate white feminism from women of color, to queer people, to a lot of CIS men I've encountered throughout my career. Again, it goes beyond one particular person it's an entire way of seeing.

[00:07:35] Anna: So what are some of the kind of core tenants to it? We'll dive into some of them more specifically, but if you can just kind of lay the framework for what are some of the the main pillars of white feminism.

[00:07:48] Koa: Well, one of the biggest ones and I'll share some more sort of like sub pillars under that, is that the true hallmark of white feminism, whether we're talking about now or a hundred years ago, and I, I do trace this ideology to it's very important roots in the United States, particularly with the American white women's suffrage movement, is that white feminism has always asked that women and non-binary people aspire to be seen in the movement.

And what I mean, when I say that is that white feminism has never met marginalized genders, where they are in terms of the blockades to financial security, to having a political presence, to changing, you know, structures that marginalize genders. It asks that you aspire to be this, you know, middle-class woman, who's in a heterosexual marriage who aspires to motherhood, who wants to own a business who wants to be a leader in not just the political sense, because I think there's been a lot of, you know, leaders throughout different types of feminism, but specifically a leader in a capitalist sense. A big tenant of what some people quantify as first wave white feminism.

So the, you know, middle to upper-class white suffragists who were organizing around white women having the right to vote and thinking about that, their template for empowerment equality. However you want to think about it was literally their husbands. So, their husbands, their sons, their brothers, literally seeing the men in their life, leave the domestic sphere, go into businesses that they owned, and did not necessarily, you know, work in a low wage capacity.

But also the presence they had in the political landscape, because they did have roles and sort of like leadership opportunities that were heavily economically based. So this endorsed today, and I have a lot of examples of this, where, you know, for many people in my own country and internationally, a big white feminist talking point is like, well, men do it and it's okay for them. So why can't I also, you know, run an exploitative business where I systematically fire pregnant women, or I do not provide decent health care that includes birth control, or I work new parents into the ground and eventually fire them.

And the thing is a hundred years ago that was a very similar core belief, and many, many, many other feminisms that I documented in my book, Chicana feminisms, black lesbian feminism, working class movements, fat politics, disability justice, all of these different lanes, queer movements as well, they're not interested in ascending to be the quote unquote men in the United States and to have the power and dominance that they have. A thread that connects all those other feminisms is rethinking power structures, rethinking the distribution of resources. And white feminism is very anomalous in that it has never been about rethinking structures.

It's always been about ascending in the structure as it is. Another key component to white feminism that I think is really unique to it as a practice is that white feminism has always heavily embraced commercialism and marketing. And, I approached this, in the research of my book from honestly a very earnest place and when I was coming up in newsrooms and I document this in the book, this whole idea that pop stars, right, would like talk about their feminism and try and sell you things that say feminist on them. And then, you know, nevertheless she persisted t-shirts and like feminist AF mugs, at the time, I approached that as very weird and anomalous and not really indicative of Feminist politics, but also, the reduction of say like a feminist response being commercial, right?

My feminism suddenly becomes transactional. I pay $12 and I get this mug. And then the mug is supposed to distill and advertise and affirm to people around me that I am a feminist, regardless of how I vote, or, if I support a union or, many other things that I might include in my feminism, like criminal justice reform or whatever.

And at the time, I really thought this was a sort of new very late capitalism practice, right? This idea that like, I have to buy everything about my identity, but I learned through the research of this book that that practice is actually not new at all. And white feminism has always operated this way.

In the turn of the century, when a lot of the, again, what some people call first wave, middle to upper class, white suffragists were organizing how they were gonna popularize this notion of white women having the vote in the United States, they turn to marketing and they literally designed in house who a suffragette was and keenly, you know, who you were supposed to think of when you thought of women's rights in the United States. Um, you're supposed to think of this very thin, white woman who was young, who was able-bodied, who aspired to a heterosexual marriage, who don't worry, she still wanted to have children, she shopped a lot, she had a strong economic presence and what they essentially affirmed with the popularizing of that message is that suffrage wasn't trying to complicate or rethink what a woman was. They were sharing with the broader nation that they agreed with who a woman was. And more importantly, who a woman should be.

And marketing and commercialism have always been a very big part of that in white feminism. These particular suffragists who I was just speaking about, you know, they literally partnered with Macy's. To not only declare it the headquarters of suffrage, I go into a lot of details about this in my book, but also to sell you again, a lot of things to cement, to the broader population that you supported suffrage again, through transaction through money.

There was an official suffrage outfit. You could buy all these like flags and luggage tags and all sorts of like decorative bobbles that were, you know, pro suffrage. And again, a lot of these initiatives and practices came from the suffrage organizations themselves who a lot of their motivations for doing this, which I also think are pertinent, is that they were trying to combat the inevitable misogyny that would come with women who spoke publicly, women who had opinions about things outside of the domestic sphere, women who had opinions that might differ from the men in their family. And they were very aware as women of their era about the torrent of misogyny and harassment that would come from again, speaking publicly, having opinions. And I think it's really telling about the way white feminism operates now and a hundred years ago, that the way to combat that was through commercialism, through marketing, through selling products and that endures

[00:14:51] Anna: Yeah, absolutely. And I don't want to simplify it in any way, or oversimplify it, but what really strikes me about this ideology is the parallels to the patriarchy itself, which feminism is fighting against. So obviously within patriarchy, men are positioned as the kind of standard and women, a slight deviation away, and there niche and relegated to the footnotes of our story.

You know, that's kind of the premise of this podcast, but white feminism is essentially doing this same thing where exactly, as you say, you have this one kind of woman who's the standard and anyone else's de-centered. And as you mentioned in your book, maybe they get one anecdotal mention and just like the focus has been on building a world that best suits men, or at least some men, the focus with white feminism from the suffragette til today has been building a world that best suits one kind of woman. And of course, that woman is very conveniently aligned with those same men. Do you think that's kind of a fair parallel to draw and then is there anything you would add to that point?

[00:16:05] Koa: Yeah, I think that's fair. And also I think that it's really telling to me as you know, somebody who is a journalist, who is a researcher who really looks to history to illuminate a lot of dynamics that are happening now, politically and culturally that white feminism in particular always afforded this narrative in my own country as being the default feminism. When you think of feminism, you're supposed to think of this particular movement and these particular women. And that's just not true. Uh, feminism is a very big tent. There are many movements, many ideologies, many strategies, and there have been a lot of very critical thinkers of gender oppression across race, across class, across gender presentation.

And yet it is white feminism that is afforded the, you know, capital F, in our country. And it speaks a lot, I think, to the dynamics that we just said where, white feminism does not ask that institutions or organizational bodies or, powerful legislative branches change that much.

It's never been about that. And I think that that speaks a lot to why it has endured and why it is afforded this legacy of being the default feminism in that powerful bodies for the most part are okay with white feminism. It's very palatable. It encourages that you, you know, shop your politics, that you remain a very industrious worker that you feed this system that marginalizes others. And clearly only ensures that certain people at the top are afforded, not even just a basic standard of living, but you know, a higher standard of living. White feminism keeps everything intact. And I think that's why it's endured.

[00:17:54] Anna: That was actually gonna be my next question is why you think that it has endured for so long. No, that's, that's absolutely perfect. I mean, I like this quote that you said on that realm, which is "white feminism takes up politics of power without questioning them by replicating patterns of white supremacy, capitalistic greed, corporate ascension, inhumane labor practices and exploitation, and deeming it empowering for women to practice these tenants as men always have."

I also liked how, at one point in the book, you referred to it as a better version of bad, because I think that's what people think, it's like, "well, we want women CEOs" and yes, of course we do. You know, no one is saying we don't want that, a few decades ago, it was a very different situation with women in leadership. And of course we want that, but that's such a tiny portion of women in such a blinkered view of the full scope of the problem that that's nowhere near the measure of success that we're after. And also at what cost? Exactly as you say, that just perpetuates the current systems that aren't working for the vast majority of people, which we'll get into.

So you've talked about how, you worked for these different mainstream women's publications, Marie Claire Vogue, Jezebel, and this was during that time when feminism was undergoing this resurgence and becoming cool again. So is there anything else that you would add to that? You've talked a bit about the commodification, but what did you see from your perspective of how feminism kind of transformed in the mainstream and within these publications and how does that stem into today's version of white feminism?

[00:19:35] Koa: To answer your question directly, I saw a lot. And part of that is what motivated me to write this book. I think, especially coming from, I'm mixed race, I'm queer. And I think in a lot of ways, especially when I revisit a lot of feminist texts that have been very important to me, you know, not just in my career, but just in my life, I've gotten way closer to institutionalized white feminism then I think a lot of people from my background have, and in thinking about this book and in thinking about who would use it and how it could be used, um, a big part of what motivated me to do it is that I should write down what I have seen, because I have certainly relied on that with many feminist thinkers and writers who I admire, the fact that they wrote down what they saw is incredibly pertinent to, again, not just things I write things I think about, but literally my life.

To address the timeline, as you said, Anna, I started my career in journalism right around the time that, quote unquote feminism, however you're thinking about that, was suddenly deemed less taboo in the broader culture. And I go into some detail about this in the book and that when I was growing up, which frankly wasn't really that long ago, feminism was a dirty word.

It was a taboo thing. And I cite many cultural touchpoints to distill that in terms of comments that were made in the broader culture, but to put it like really crassly, to be like outed as a feminist or be called a feminist when I was a teenager was paramount to being a social outcast and being, you know, que the like homophobic lesbian jokes and all of that sort of thing, which still endures.

Um, but I think at the point that I was working in newsrooms that was starting to change and it started to change with a lot of very high profile famous women saying that they were feminist, in the way that they thought about their life, their career, their partnerships. And that's really where I started to see a shift where all of a sudden you could put feminists in a headline, you could interview a very prominent, visible woman specifically about her feminist politics. That was new. And I cite many examples in my book of many reporters talking to women like Taylor swift or Kelly Clarkson and a number of other prominent women in business.

And them, collectively just kind of saying like, I'm not a feminist, how dare you imply that? Um, so it's, it, it, and it happened really fast. And at the time, I'm a graduate of a women's college in Northern California, Mills College. And so, I studied gender in a very acute, intentional way. I mean, I walked into a small liberal arts private school and was basically like handed bell hooks and made to think very critically about gender as a very young person. And so for me, graduating into this, you know, white collar job marketplace and suddenly being able to cite thinkers who have influenced me and to like, use these terms, that was a really big deal.

But as I get into in the book, what I started to notice as I got further along in my twenties was, oh, okay, so like, when my feminist identified boss says feminist, and I say feminist, we're actually talking about two different things. And that took me a minute, you know, especially in real time to be able to strategically piece together and understand. Particularly in this moment where feminism was treated as this like exciting thing that we could throw a lot of resources behind and we could talk to, you know, different women about gender biases that they have experienced.

I mean, I cannot stress that enough, that was like not done in the mainstream culture. But part of again, what traces back to this book is that I started to realize literally in real time, you know, in meetings, in directives from feminist identified bosses that actually our feminisms are very different.

I want to talk about affordable housing and poor women not being able to afford diapers. You want me to report on like mompreneurs on Instagram and women establishing small businesses, like beginning, middle end. And so it's a very different interpretation of gender rights.

[00:23:53] Anna: Yes, very different indeed. And you even talked about how you would pitch some of these ideas and they would get classified as like a niche topic. Yeah,

[00:24:03] Koa: Yes. Yes. And I, a big part of my professional twenties was pitching ideas that were about gender or feminism or whatever. And then again, getting these notes back, that would be like "No Koa, like we're not talking about those women."

[00:24:19] Anna: Hmmmm

[00:24:20] Koa: But again, you know, a lot of my bosses and managers, it was very coded the way that they would say this to me. It's not like anyone pulled me into a meeting and was like, "Koa we don't want any ideas about Latinas. We don't want that." They would do it in more subtle ways. You know, I would pitch things about, trans men carrying babies to term and how this was changing the health care industry. And I would be literally told that that was a niche idea.

[00:24:45] Anna: Wow.

[00:24:46] Koa: Yeah. And so, you know, what does that message to me as the reporter and editor on the ground that like, these are people who experienced the system of our world, whether it's healthcare or not, who are not as central to feminism as like the CIS straight white lady who, again, wants to like climb to the top of the corporate ladder, which by the way, we have a ton of stories on.

[00:25:08] Anna: Yeah. Yeah. We've got lots of those.

[00:25:13] Koa: Yeah.

[00:25:14] Anna: On that kind of note, part of this white feminism ideology is this meritocracy belief where, you know, it's up to the individuals fate and you can prevail over institutionalized sexism, racism, and classism, simply through your personal will. But of course in this world of perceived meritocracy, the flip side, is that anyone who isn't succeeding by these standards, not only doesn't get written about first of all, but these individuals and communities aren't just seen as unsuccessful, but often they are blamed for these things.

Because if the narrative is that it's up to the individual to succeed, then it's also on the individual. If they don't. And that's obviously grossly inaccurate, but I want to talk what the reality is for these women, because while white feminism sees success as being a girl boss, CEO, there are women who see success as being able to put food on the table at the end of the day.

And as you put it in your book, opening lofty educational opportunities to people who are food insecure will not help them. So can you talk about the realities of what life is like for women who aren't centered in white feminist ideology and how white feminism perpetuates their circumstances?

[00:26:36] Koa: I write extensively in my book about what life is like for those women and non-binary people and it's not great. And I finished my book right as like COVID was already bringing so many institutions to their knees and changing a lot of really tenuous safety nets in the United States as they were, and then COVID decimated them.

Something I go into a lot of detail about in my introduction to sort of set this for you, is that a lot of the, as you just said Anna, like meritocracy narratives about white feminism have been very successful in conveying, I think to the broader culture that feminism is just everywhere now and that, you know, everything's great for women.

For many women and non-binary people, feminism has not come at all. In my lifetime, for instance, I just turned 35 and for my entire lifetime in the United States, black women have closed the wage gap with white CIS men by 9 cents. Less than a dime in 35 years. Latinas are fairing even worse for them. It's literally 5 cents. And in the United States, the cost of living keeps ascending and climbing. The cost for, you know, a college education has just continued to inflate and yet wages for a lot of women in those industries remained pretty stagnant. And so even if you do believe in this whole, like, upward mobility sort of idea that if women just worked hard enough or were, you know, I don't believe this, but I'm just saying broadly, the long division of white feminism doesn't even check out because, many of these women who I decided who work in caregiving positions, many of them are domestic workers, some of them work in nursing, these avenues just frankly, don't exist for them. And it's been enduring and again, the last like three decades. Another thing that's worth mentioning is just the rates of female incarceration in the United States. I cite the statistic in my book, but they've grown 750% in my lifetime in terms of women in jail. And many of those women are mothers. They have young children.

And so again, I think one of the weird, sort of like fun house mirrors that white feminism does with our culture is that it shows you and perpetuates a lot of this data, that the, number of women say for instance, who have been getting college degrees in the United States have grown considerably in my lifetime over the last, I think like four decades, it's just been on a constant uptick. Pre COVID, the number of female business owners was through the roof and many of those business owners were black women specifically.

And yet, that's really white feminist data. Those are women who have been able to ascend and exist in a structure to obtain a lot of this. Most women are of a second tier of data, which is many of them are incarcerated and many of them make low wages. And yet this is the data that does not make it into the white feminist narrative because it's based in meritocracy.

[00:29:57] Anna: So what has changed with the pandemic then? Have we learned any lessons about the realities of white feminism?

[00:30:05] Koa: I think it depends on who you talk to. And honestly what you read. I've encountered all kinds of narrative and data since the COVID pandemic has taken over, many of it, white feminist. I'll give you an example. I wrote a piece for Time earlier in the pandemic, around the time that my book came out, basically distilling the white feminist narrative that was emerging around COVID. And what I mean when I say that, is that the number of white collar job losses for women in the United States were being translated very flatly in one dimensionally in that COVID is setting back feminism.

And I mean, it's very myopic on one tier, but also a lot of what I wanted to pick apart and analyze with that narrative was that feminism in those contexts was only being quantified as white collar work. That having all these women in lofty leadership positions had been front to back feminism.

And I, I don't agree with that as you stated earlier, I think, for many non binary people and women in the United States, feminism is them having access to decent healthcare. It's about them having a decent wage specifically as a domestic worker, it's about them being able to be home with their children and to engage with them in a meaningful way in the first part of their life.

It's not solely making a lot of money for a company air go themselves. And in COVID this narrative was already emerging. I think what's also interesting, when I was picking apart and analyzing a lot of those reports and narratives is that the big overarching thrust for this was, white collar women are are losing their jobs and feminism broadly should be concerned about that because this is what we've been working for.

And yet, you know, in a lot of data that I've been across and that I specifically looked for to write this piece, so many domestic workers and cleaners for instance, a female dominated profession, lost their jobs in COVID and you know weren't able to pay their rent or mortgages, weren't able to maintain a food secure household.

And many of those women are mothers of children, and yet, them losing their jobs is not seen as a crisis for feminism, which really says a lot about who's being centered in that narrative, but also much like the white suffragists of the turn of the century, the woman you're supposed to think of with women's rights.

You're not supposed to think of immigrant women who come to your home and take up a bunch of labor so that you can then leave. And make money outside the home or start a business or spend more time with your children or your partner, if you have one. You're supposed to think of once again, the middle-class woman at the top of a corporate ladder. And that's where your feminist consciousness is supposed to focus.

[00:33:13] Anna: The ones who are leaning in...

[00:33:15] Koa: Yes

[00:33:16] Anna: ... versus the ones who are being leaned on.

[00:33:20] Koa: Yes. Correct.

[00:33:21] Anna: I liked that, I mean, I obviously don't like it, but the wording it in that way and thinking about it in that way. Could you talk to that point a little bit, the problem that you see with capitalism as it relates to cheap labor and then what you defined, for anyone who might not know about the lean in narrative, even though I feel like that's pretty well known by now. And then how that relates to the lean on?

[00:33:45] Koa: If, if you don't know about the lean in narrative, I envy you, at this point. Um, so I cite in my book many feminist thinkers and writers who, prior to my book, coined this phrase leaning in actually means leaning on. And what they mean when they say that is that the structure of our country right now with regards to labor and particularly earning money outside of the home requires that you lean on underpaid, usually immigrant women to come into your home and take on a lot of labor that you, or your partner if you have one, cannot do because of the mandates of your job. During COVID this seems to have shaken some people's consciousness around that. In that again, the way that my country is constructed is that the total domestic sphere, care of the home cooking of food, doing dishes, making sure your bathroom is clean, feeding and bathing children if you have them, none of this labor is factored into the economic model that dictates our entire country.

And so during COVID, for instance, you had a lot of, I certainly heard from them, previously I'll say like white feminist identified women who, you know, were indoctrinated into this narrative and leave their homes, pursue these really high performing corporate jobs, had a team of low-income women taking care of more like traditional women's work, we'll say so that we can do this. And yet during COVID when everybody who was in white collar work had the avenue to work from home, a lot of their systems of care, completely vanished. And for other people who I think were very sort of narrow in their understanding of gender rights and gender progress in this way that was very individually focused, I think this was very sobering for them. Because structurally a lot of things about our country have not changed. And therefore the work that is deemed yours specifically because you are a woman, has not been reinterpreted on a structural level. You're just supposed to outsource it. And again, that's not a structural change.

In other countries we're looking at things like universal childcare, we're looking at say like a federally recognized paid parental leave or family leave or, you know, sick leave, that was another component in that family members catching COVID, being ill, needing a certain quality of care, that has not been factored into a lot of foundational elements of our country.

And I do think that the criticism of that belongs there. I don't think it necessarily belongs at small business owners who don't have the resources to magically like give all their employees, right, like a year off, paid parental leave. I think the only people that can afford to do that is like Facebook, right. Um, you know, Facebook makes a lot of money, so that's how that works. But again, I think it, it belongs on a government scale. And yet the origins of this through and through are that the domestic sphere and labor of the home have not been considered by our country. And COVID, I think for a lot of people who had not considered that was very earth shattering in that exact moment in that you are literally in your home trying to work outside of your home in a white collar capacity, and yet, dishes still need to be done. Your kids need to still be fed and bathed and effectively for a lot of people in my country, homeschooled, that was like a new lane.

And so think an important way to think about this is that a lot of labor that has been deemed traditional women's labor in the United States has one not been given any resources, but just consistently deemed as infinite, that it'll just always be there, that it will endure, that it doesn't need anything like rest or resources. And white feminism has inherited this and not questioned this. And yet I can't say it enough, many other gender movements and feminisms have.

[00:38:00] Anna: Yup. I liked your line that how COVID showed us that white feminism wasn't made for this real life, it's an aspirational fantasy. And really exposed all these shoddy systems. Exactly as you say. So there might be some people that say "Koa Beck, why does she have to write a book about white feminism and the problems within feminism? Why does she have to be so divisive?" So can you talk about these 'stop being divisive' lines and it gets used in certain instances?

And, and

[00:38:34] Koa: Well, two things I'll say to that. One being, you know, in terms of myself and like my own positioning, I consider myself part of a very long line of feminists who have questioned white feminism. I'm part of a legacy now of really incredible thinkers who have organized with other women, non-binary people, who have thought about gender in a very critical way who have tried to organize or write, or build coalitions, and have come up against white feminism. And I think it's very important to think about me in that broader historical context and that I am by far the first person who has questioned white feminism and wrote about it very critically, many other people have. And many of them I admire and look up to.

Secondly, the mandate to stop being divisive. I go into a lot of detail about this. I have been told this many times, both to my face, but also in, again, I think more like coded terms and where I've landed on that specifically for the book in terms of white feminism and how white feminism uses this terminology is that, you know, if you're a low-income woman, if you're a woman of color, if you're queer, if you're trans, if you're an immigrant, if you're fat, if you're disabled, and you're in that one-to-one dynamic with a white feminist or white feminism broadly and you're saying something that deviates from the white feminist mandate, experience, history, interpretation of gender progress. And you're being told that the experience you've had, that the experience that other women in your family have had is divisive. I interpret that as white supremacy, really in real time, in that the feminist experience is being homogenized as the white feminist experience and the data and experience that you're sharing about being a black woman, being a lesbian, being an immigrant, being disabled.

The fact that that chips away at white feminist interpretation, that's the point. That's why you say it, that's why you share it. And so to be told that you're being divisive really indicates to me that that is a white feminist conversation and a white feminist interpretation in that, of course there variances in gender and gender oppression and gender experiences. And yet those differences are being suppressed and that is peak white feminism.

[00:41:08] Anna: Peak. Absolutely. Absolutely. I mean, I've heard that thrown around as well, and there was a couple other pieces of languages that I wanted to mention. And have you comment on, because I've also heard these as well. One being the white privilege disclaimer, and the other being lucky.

[00:41:27] Koa: Yes. Oh my God hearing you say that. I just, like, I just viscerally came back to a newsroom that I used to work in. Um, so, I appreciate you asking those. So the first one white privilege, something that I became aware of in my time in newsrooms is that a lot of women who I deem white feminists and again, I think it's important that I distinguish this in that these are white feminists. These aren't feminists who happen to be white. I think that's a very different interpretation. I intentionally include in my book as contrast the underreported history of anti-racist white women in the south to show you examples from history of women who were white, but who did not bring aspirational whiteness into their feminism.

And I think that's really important. So anyway, white feminists, not women feminists who happened to be white. I became aware of a number of white feminists in my job, couching a lot of their opinions in beliefs with this sort of white privilege disclaimer, which, you know, sometimes they would literally cite it as that, but other times they would use other interchangeable things like, well, you know, I'm a white girl from the suburbs, but TK, TK.

And you know, what I didn't find helpful in those conversations is that I think there's a way, especially in this, you know, weird landscape where we're all scattered across all these different hierarchies and we all have access to different power based on where we were born and the education that we have.

I think there's something to citing that and stating that in a really direct way, and also like pinpointing yourself, right, on the spectrum of all these, you know, different identities and also like class advantages. But what I noticed in my line of work is that it was often used to sort of like close the conversation, not to open it up. And again, I go into more detail about this, but it was often used as like I'm acknowledging that, I grew up in a food secure house and that I had access to college and that I was able to afford taking a low paying job. So that could now be here in this like lofty office. But I still think that, you know, we should only be profiling thin young women.

[00:43:49] Anna: Yeah.

[00:43:50] Koa: Um, and it's very strange how that disclaimer worked. Like in real time, I would literally be sitting there thinking like, what does this even mean when you say that, like, you're acknowledging that you are disproportionately advantaged in the system that we're, you know, critiquing as feminists or however you want to think about that.

And yet you're still asserting that your opinion, your point of view, your sort of curation of what feminism is, what culture is, should be respected. I think this overlaps very cleanly with the lucky terminology in that in a number of pieces that I had to edit, a number of interviews I did, I became very cognizant and aware of young, white women in power suits, literally sitting across from me in some instances or just being on the other side of a piece and really addressing how lucky they were. And they would use this term lucky, lucky, lucky. And it was almost like a tick, this like code that they were all sharing. And I started to realize through additional research I did reflecting on these professional experiences, that lucky is a very particular word to use in these circumstances where a woman who's very wealthy, who is very visible, who is from a middle class background, is in some ways addressing the disproportionate distribution of resources. Right. She's acknowledging it, but she's not critiquing it. And that's where lucky, I think is a very choice word to use. I go into a lot more detail about that in my book, but I think it's pertinent when you're talking about specifically white feminists or white identifying women who are from certain backgrounds, acknowledging some sort of privilege, but then reasserting it, as if the acknowledgement is supposed to make that reassertion like more copacetic. Unclear.

[00:45:48] Anna: Yeah, like that that's enough. I like how you called the privileged disclaimer, the col-de-sac of white feminism: the way you go in, you do the motions of racial and queer consciousness, and then you just come right back out the same

[00:46:01] Koa: Yes.

[00:46:02] Anna: would add and think that that describes it quite well.

And one more point on that, because I also like how you point out to the luck bit, okay, "those who find luck are white, wealthy able-bodied cis-gender straight, conventional femininity. And when you line up all of those factors, you aren't looking at random good fortune. You're looking at the mathematics privilege and how these distinct advantages have destinies in our America." And also like you point out, that doesn't mean you didn't work hard. Cause I think that's like a big thing with people who have privileges. They think this erases all of their hard work. It just means, as you said in the book, I love this line. It just means "you have the opportunity to work hard in the first place."

You've mentioned in the beginning that there are white feminist men. So is there anything specifically, that you would comment on about them and then from your perspective, what do men stand to gain in a more gender equal world?

[00:47:06] Koa: I think a few things off the top. I think that primarily, you know, the idea that men have something to gain in feminism, loosely, I think alludes to a lot of structures that we're trying, or I'm trying, and many thinkers I site are trying to take a part in the first place in that, you know, specifically, like why do CIS men have to gain anything?

Um, they, they, they live in a culture that constantly affirms them and affirms, you know, many of their impulses and denigration of others. And so I think in redistributing resources, power, gender roles, trying to frame it as something they will gain kind of defeats the purpose. Having said that, I will say that patriarchy and misogyny, I think really has the capacity to divorce CIS men from some very vulnerable and important parts of themselves. I think that the roles of patriarchy really limit CIS men and limit their ability to have full emotional lives. Whether that's with like partners or friends or children, if they have them. And I think that men are constantly . Messaged through a lot of ways in our culture that like that's not only okay, but th that is a cornerstone to like being a man broadly, you can take that in a lot of different narratives.

And so I think ultimately that's very sad for them. And I think that their inability to have a full range of emotions to connect with other people, to experience, you know, sadness and depression and remorse and loss, and then also to build meaningful connections with other people, whether it's like in their family or again, potential partners or children, they may have.

I think also, you know, I'm not the first person to say this, but gender is a construct, could not be like a better phrase. Like you can't really improve upon it. It's such a clear mandate. And so I think a lot of even just the fact that feminism traditionally and historically has not only asked that we rethink gender roles, but also rethink gender. What does that even mean when we say that? The fact that, you know, we're supposed to believe that there are only two, which I write about this a lot in my book with my experience at a women's college, but, you know, that's a very Western capitalistic classist sort of interpretation of gender anyway.

And so I think that the bigger question to ask here is not only what men can gain, but what can feminism do? You know? For gender, in that if we're not locked into these like really weird scripts that are culturally sanctioned, but also economically sanctioned, what is possible for us outside of like money or, having lofty professional roles, but like what, what is actually possible if you can drop all of these like weird scripts that are so tied to our economic wellbeing, but also our access to like certain healthcare and our ability to maintain affordable housing. I think that's the question I would pose back.

[00:50:35] Anna: I love that. So looking forward, what does a new era of feminism look like and what do you think the pillars of change are that it's going to take to get there?

[00:50:50] Koa: I think a lot of things about that. Um, very, very, sort of bulleted, I'll say that one, I spend the last third of my book addressing that, you know, in, in sort of a, like a course correction kind of a way for white feminism. But also just as I think, just more evolved place to anchor feminist consciousness.

I advocate in my book one, first and foremost, really anchoring your feminist consciousness in basic need. I quantify that in my book as access to clean water, food security, affordable housing, criminal justice reform, and, healthcare access. Many other feminisms that I analyze in my book, that's what they all have in common. They're not about one woman in their community, right, ascending to having like a certain standard of living and then everyone else mimicking her to fit into that structure. It's about everybody having access to a place to live that they can afford, having access to clean water, being food, secure, things like that. And yet white feminism often starts at, I think you said it earlier, Anna, but white feminism starts at really lofty educational opportunities and small business and enterprise, which I would consider more on like the top of the pyramid.

[00:52:08] Anna: Yeah...

[00:52:09] Koa: um, yeah. And yet I think for many women who have been indoctrinated into white feminism or who have perpetuated it, I think the reason it starts there is because their basic needs are already met. These are literally things that they don't think about. And so they're not a bedrock to their feminist consciousness.

I also advocate in my book, really mobilizing against systems rather than individual people. I witnessed this a lot with me too, which I covered in the job I had at the time where the reporting of me to, like initial me to, that was the most captivating and revealing to me was not so much, you know, this incredible like monster at the top who was abusing people, particularly junior employees, but more so, the layers of people in these companies and institutions who knew and who knew, and for whatever reason did not have the power or the capability to either challenge it or connect with other people to understand the scope of it, you know, in the organizational body. And so from where I sit, after this many years of reporting and going into this book, it's like, you can, you know, replace a metaphoric, Harvey Weinstein, but what about the system and environment that facilitated a metaphoric, Harvey Weinstein, if you just replace that person, which a lot of companies did on record, it's unclear to me how that environment will not produce that same dynamic.

And so, you know, thinking more in terms of policies or structural changes that can happen rather than focusing solely on this one individual person and getting rid of them and then, you know, just like hiring a woman

[00:53:57] Anna: Yeah. The one savior

[00:53:59] Koa: Automatically be better even though she's, you know, reporting to the same board. Right. And has like probably the same performance metrics and is being held to the same standard that, you know, he was professionally.

The other piece that I think is really important, particularly in shirking white feminism and being conscious of it when it's in the room. And in some cases, you know, not allowing it to take root in the room is to not acknowledge privilege, which again, we've talked about, but to push for visibility instead, to not have, you know, these like armies of, really privileged white women repeatedly tell us that they are privileged. And then to assert the same agenda, the same, you know, in my case, like editorial calendar to push for the same initiatives, but to have people visible in these roles and advocating who are not necessarily from these backgrounds.

And then the further point I'll add to that is that they're not, you know, tokenized. I go into the dynamics of institutional polishing in my book, which I cite from Sarah Ahmed. Who's a very incredible feminist thinker. I highly recommend her book Living a Feminist Life. And she talks about pretty extensively the dynamics of institutional polishing, which are essentially when you know, somebody who's not a CIS white man often is hired.

The really crass term is diversity hire, which I've heard a lot in my career and I consider it to be a very derogatory term. And, you know, they are hired for either their diversity work, that's very broad and loose or their background or a number of other factors. And yet once they get to the role, they figure out very quickly that they're not actually supposed to change anything.

That's not what they were hired for. They were hired to metaphorically and you could argue in some cases, literally, polish the institution to make it look a certain way, rather than challenge any of the dynamics on the inside. So I think that fighting for visibility has to take on a literacy of that dimension.

And the last thing I'll say is that I go into a lot of detail about this, but I really do believe that our feminist future is our collective. Future it's in the way that we view each other. I think that the way that my country is structured specifically, in terms of education and resources, and even just, how cultures and histories are taught in our public school system has been very effective in taking us away from each other or so siloed to the point where readers of my book, I mean, I said this to you, Anna, before we started recording, but you know, readers of my book who are stay at home moms in the Midwest and who have otherwise been indoctrinated into white feminist politics, write to me and say that, you know, they didn't know anything about indigenous women's rights in the United States.

They didn't know that "the future is female" is from lesbian history. And you know, that is unfortunately the repercussions of us being taken away from each other and really existing in these privatized spaces where we do not learn how each other has been subjugated, but also what other people have been fighting for for a really long time.

And so I think that closing that, you know, whether that's through education and a number of other measures, but also looking out upon people who are not you, who do not come from where you come from, who didn't go to your college. I think that's very indicative of our feminist future in terms of viewing them within the context of their culture and their lives, but also them having value, that is not sanctioned in this like, highly capitalistic, like corporate way.

[00:57:44] Anna: Absolutely. So for those people who are hearing this concept for the first time, is there anything that you would say for how people can begin to identify this within themselves and reframe their perspective?

[00:58:00] Koa: Yes, very much so, I talked to a lot of people who close the book and still wrestle with that after the fact. And I'll say first and foremost, that, you know, white feminism is extremely powerful and very seductive. And that the fact that you can, you know, close the book on white feminism and still have white feminism knocking around in your mind in terms of how you approach social justice, how you approach thinking about gender rights, that's kind of to be expected because again, the phenomenon and ideology is so far reaching. As Anna, you just said, I would advise that you not come to this, centralizing yourself. If you are someone who recognizes yourself in this book or in this conversation, white feminism has often cast you, metaphorically, as the maker of all change.

And again, that's one of its tenants is that you will walk in, you know, with your like venti coffee and your pencil skirt, and you will erase sexism from the corporate body you work for or within like certain government institutions that you participate in. And history has shown that that is just not true.

And it also, in some ways minimizes the scope of what we're working against in the first place, no one person can do really anything. And again, white feminism silos us, it makes us highly individualized and it makes us look inward rather than outward. And so the place that I would advise that you start is to not start with what can I do, because again, that is a script that white feminism has given you.

I would advise that you look out and begin with an assessment of the women and non-binary people in your neighborhood, in your work, in your, you know, children's public school, if you have them. And what I mean, when I say that is like, don't, you know, walk into your white collar office and just look at like the other say mid level white collar employees who are also women. You need to think about the women who come in and clean your office after everyone has left.

You need to think about the caregiving responsibilities that a number of people in your company are basically handing over and outsourcing to low-income workers so that they can be there in the first place. You need to assess a lot of the environments and structures that you walk through from a holistic sense and think about the structure and what that structure asks you and other women who are perhaps not like you to maintain and perpetuate usually from an exploitative standpoint. I advise coalition building across race in some ways across the gender.

And what I mean when I say that is that, if you're in a company, for instance, a white collar company that is really devaluing women's labor, and you can put a monetary sign on that. Like if you know a number of women in your company are noticing that the CIS men are getting paid way more than they are for literally the same work.

The white feminist narrative is that you look inward, right? And that like you go to HR and that you negotiate and that, you know, you, really, push for your own value in the company. If you are experiencing that, probably there are other women in the company who have experienced that too. And so I would advise that you not come at that from a very individualized place, but then all the women in your company who have experienced this really work together to go up against the power of the company to challenge this so that if there is any sort of conclusive measures on this, you're looking beyond, you know, the singular woman who negotiates her way out of a wage disparity with her male colleague and then leaves that HR office having secured a strong financial future for herself.

What about the other women on the floor who are probably in that same predicament and maybe don't know or don't know that.

And So I would start with not thinking about yourself, start with thinking about the way that you exist in a structure and how other women and non-binary people have probably experienced what you have experienced, and that hopefully will lead you onto a freeway on ramp of collective action, rather than assembling your own sort of private toolkit to battle institutionalized sexism.

[01:02:36] Anna: Amazing. One more question before I move on, I really loved at the end of the book, how you ended with this beautiful quote by Harriet Tubman, that Viola Davis said in her 2015 Emmy's acceptance speech when she was the first Black actress to win an Emmy for outstanding lead actress in a drama series.

And I loved what you said about that line and what it signifies and who should be crossing which direction. So I'm going to play what Viola said, quoting Harriet Tubman. And then I would love if you would share what you think about this saying and about this line.

[01:03:15] Viola Davis clip: In my mind, I see a line and over that line, I see green fields and lovely flowers and beautiful white women with their arms stretched out to me over that line. I can't seem to get their know-how. I can't seem to get over that one.

[01:03:45] Koa: I listened to that speech so many times when it came out and I really admired that Viola Davis, in accepting the award, just went up and started talking and didn't say, you know, in accepting this award, I'm going to quote Harriet Tubman. Like I love that she just went up and said it. And to me it really conveyed a certain timelessness in what she was saying.

And that we didn't know until, you know, many sentences in right that she was quoting Harriet Tubman. And in some ways, you know, as an author and a journalist and a historian, that's kind of the point, right? Like she can walk up there, in the era that she did and say literally words from Harriet Tubman and they're applicable to her exact circumstances.

And I think that's incredibly powerful. And I loved her delivery. But for me, in my life, in my line of work in what I tried to cover particularly with this book, I spent a lot of time reflecting on that speech. And then also, you know, after I heard it, then I went to go look for the original Harriet Tubman passage, and to understand a lot of dynamics under which, you know, she said this, and I thought about it a lot in terms of my challenges with white feminists and particularly, not other women, but literally me, you know, going up against white feminism and what that feels like. And I had this really, particular moment, a couple of years after that speech where I realized, and I address this in a lot of detail in the book and that, you know, that line, that Viola and Harriet are referencing, you know, that's not for me.

And like, I've really tried to get across it in my professional career. I've really tried to, in some ways go up against white feminism by myself. And I mean, it's incredibly hurtful and painful, but also on top of that, I think realizing that there is a division between us, in our politics and also, you know, in some ways kind of our upbringing, right?

Like our experience in the world, the way we perceive the way we're read. But I have realized over the course of reflecting on that speech and also assembling this book that I think for white feminists, the responsibility is for them to come to me and for them to come to native women and for them to come to Latinas and for them to come to Black lesbians and for them to come to disability politics, because lot of people across feminism have been doing versions of these movements for so long.

And I don't think the onus is on women of color, low-income women, queer women, trans women to, you know, be taking the hands of feminists and encouraging them to be inclusive and encouraging them to think in diverse ways. I was willing to do this book and to merge and specifically braid so many pieces of feminist discourse and activism to give you a text that I think otherwise doesn't really exist.

But also I was very firm with my editor that I was like, I'm not going to end this book by giving women of color, marginalized women, tips on how to like overcome white feminism. That's not the point.

[01:07:00] Anna: Yeah.

Yeah

[01:07:01] Koa: The point is that this is a very specific ideology and that many other ideologies have existed and will continue to, regardless of if they participate or not.

And so I think, especially for white feminist readers of the book, I think it's important that I end the book there in terms of, you know, we've been doing this for so long

[01:07:22] Anna: yeah.

[01:07:23] Koa: In a lot of ways, it's the white feminist, right, who are late to the proverbial party and have existed in this really like hyper segregated, super elite space.

And I think that the onus is not on women of color to be your teachers or to educate you. I think that the onus is on you to drop a lot of this mythology about why you're better about why you work harder about why you should have the things that you have. A lot of these, meritocracy scripts, that's for you to do.

And for many of the thinkers I cite in my book, many of the subjects I interviewed, you know, we will be over here, doing a lot of types of work, whether that's literally political activism or organizing or writing texts or reporting, or staging walkouts or organizing unions, or all of the things that so many non-binary people and women have done throughout history.

And I think it's important that you close the book, having that perspective and an awareness for where you are situated in the landscape of gender rights.

[01:08:33] Anna: I thought it was a very incredibly powerful way to end the book. It was amazing. And as you say, that is really powerful that Viola can just stand up there and say a line that Harriet Tubman said, and it could have just been her original words right then and there. Absolutely amazing, powerful. That was a really great way to tie it all together, I thought.

So if people take one thing away from this conversation with you today, what would you want it to be?

[01:09:03] Koa: I would want it to be that white feminism is not the only feminism and it never has been.

[01:09:12] Anna: it. As listeners come away from this hour and a bit with you, are there any questions that you want to put forth to them as they consider their own narrative? Any ways they can reflect on their own experiences or anything else you'd like to ask?

[01:09:29] Koa: Yes. My question to you is who is your feminism for?

[01:09:35] Anna: Excellent. Yeah. Perfect, and then for some rapid fire questions to wrap up, what does feminism mean to you?

[01:09:44] Koa: I interpret feminism as being a response to being a marginalized gender, so that can really cut across all kinds of things. And I think it's worth mentioning that that can cut across things that I don't believe in, including white feminism.

[01:10:04] Anna: Yeah. And what is the story of a woman to you?

[01:10:09] Koa: I think the story of woman is not just relegated or mandated to the term woman. I think that the story of woman is actually a story of marginalized genders broadly. And I think there have been many and continue to be many who kind of like we referenced earlier are one unfairly, really shoe horned into two genders. So that's one, t ier, And then on top of that are made to really follow these scripts and mandates, that are meant to control them and to suppress them. So that would be the story for me.

[01:10:53] Anna: All right. That will Is there anything that you're working on right now that you would like to share?

[01:10:58] Koa: Um, I am, but I am not at liberty to share it yet. I wish I could, but we're not there yet.

[01:11:04] Anna: That is fine. Well then where can we find you? And then perhaps we can follow along for when this ready to be shared.

[01:11:12] Koa: am, you can pretty much find me on any social media platforms except tick talk. I do not touch that. Um, The book recently came out in paperback, which is beautiful. I think the designers did an incredible job. But you know, my politics are such that I don't necessarily feel comfortable asking you to buy it. You can, if you would like to, but I think it's important you understand as a reader or supporter of me and the book that I really wanted this text to exist beyond the channels of it being a product. And so my hope is that it will always be in a library.

It will always be accessible to anyone who wants to read it. And I don't think you need to have money to access and understand what I have done. And that's very important to me politically. And so you are more than welcome to buy it if you would like to, but if you do not have the means or those are not your politics, I understand that many libraries throughout the world have copies.

And if you are dyslexic or if you have learning disabilities, there's also an audio book that I read. I've been told that people like it. There are many ways for you to consume and to understand and what I have done without paying for it. And that's very important to me.

[01:12:34] Anna: Wonderful. And that's a perfect example of you living out the ideology of your book, the values of your book and not individualistic thinking, but thinking as a collective and making sure everyone has access. So thank you so much for your time today, Koa author of White Feminism, and it has been an absolute pleasure speaking with you.

[01:12:54] Koa: Same Anna. And thank you so much for your thoughtful questions and for your invitation. It really means a lot to me. And I think you're a really skilled interviewer. I hope other people

[01:13:04] Anna: Oh, Well, thank you so much. I I'm, I love to hear that. That's a great note to end on. Thank you, Koa.

[01:13:13] Overdub: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one-woman operation... so if you enjoyed this episode, there are a few small things you can do that make a big difference in helping other people find the podcast and allowing me to continue putting out new episodes!

You can subscribe, leave a review, share with a friend, follow us on social, become a patreon for access to bonus interviews and content, buy me a... metaphorical coffee which helps with production funds, or head to the website and check out the bookstore filled with 100's of books like this one. If you purchase any book through the links on the website, you support this podcast - and local bookstores! Soooo feel free to do all your book shopping there! All of these options are in the show notes.

Anything you can do is appreciated and makes a big difference in elevating woman from the footnotes of our story to the main narrative.

💌 Sharing is caring